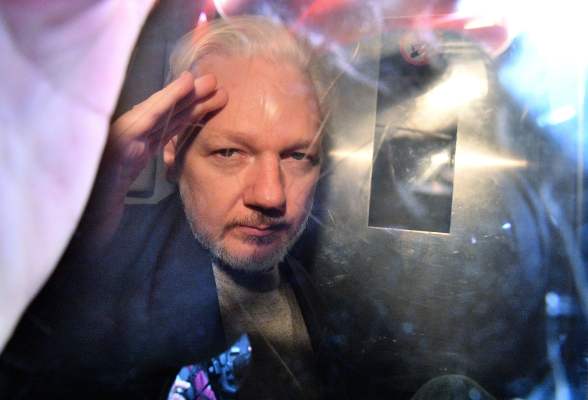

Julian Assange, founder of whistleblowing site WikiLeaks, has been charged with more than a dozen additional charges by U.S. federal prosecutors, including under the controversial Espionage Act — a case that will likely test the rights of freedom of speech and expression under the First Amendment.

Assange, 47, was arrested at the Ecuadorean embassy in London in April after the U.S. government charged him with conspiracy to hack a government computer used by then army officer Chelsea Manning to leak classified information about the Iraq War. Ecuador withdrew his asylum request seven years after he first entered the embassy in 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden to face unrelated allegations of rape and sexual assault. Assange was later jailed in the U.K. for a year for breaking bail while he was in the embassy.

According to the newly unsealed indictment, Assange faces 17 new charges — including publishing classified information — under the Espionage Act, a law typically reserved for spies working against the U.S. or whistleblowers and leakers who worked for the U.S. intelligence community.

Both Manning and Edward Snowden, two former government employees turned whistleblowers, were both charged under the Espionage Act for leaking files to the media.

Prosecutors said Thursday that the WikiLeaks founder — who published numerous troves of highly classified diplomatic cables, military videos showing the killing of civilians and government hacking tools — was charged in part because Assange published a “narrow subset” of documents passed to him by Manning while she was working as an Army intelligence analyst that revealed the names of confidential sources.

A statement from the Justice Department read:

After agreeing to receive classified documents from Manning and aiding, abetting, and causing Manning to provide classified documents, the superseding indictment charges that Assange then published on WikiLeaks classified documents that contained the unredacted names of human sources who provided information to United States forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, and to U.S. State Department diplomats around the world.

According to the superseding indictment, Assange’s actions risked serious harm to United States national security to the benefit of our adversaries and put the unredacted named human sources at a grave and imminent risk of serious physical harm and/or arbitrary detention.

The department said many of the files were classified as “secret,” meaning their release could do “serious damage” to U.S. national security.

Assange is also accused of engaging in “real-time discussions” with Manning to send over the classified files.

After Assange’s arrest in April, prosecutors had two months to lay additional charges before it sought extradition from the U.K. to the U.S., where he would be tried in court. In refusing to testify to a grand jury about Assange, Manning was held in contempt and jailed for two months. Prior to the release of Thursday’s superseding indictment, Manning was jailed again for refusing to provide testimony.

Debate remains over whether Assange, the self-styled editor of WikiLeaks, should be considered a journalist and granted protections as such. John Demers, who heads the Justice Department’s National Security Division, told reporters that Assange “is no journalist.”

But the case will likely strike at the heart of the First Amendment, which protects against government interference with citizen and reporters’ rights to freedom of speech and expression. It’s rare but not unheard of for reporters to be charged under the national security law — less so for publishing news reports embarrassing to the government but more so to obtain details of the sources who revealed the information in the first place.

Steve Vladeck, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, said the indictment will be a “major test case” for press freedoms because the Espionage Act “doesn’t distinguish between what Assange allegedly did and what mainstream outlets sometimes do, even if the underlying facts [or] motives are radically different.”

The Obama administration, which charged several federal employees under the Espionage Act during the president’s two-term administration, reportedly wanted to charge Assange too but worried it would have a chilling effect on press freedoms.

News of the indictment has already sparked anger and frustration among free speech and civil liberties groups.

WikiLeaks called the news “madness” in a tweet. “It is the end of national security journalism and the First Amendment,” said its Twitter account.

“The Department of Justice just declared war — not on WikiLeaks, but on journalism itself,” tweeted Snowden. “This case will decide the future of media.”