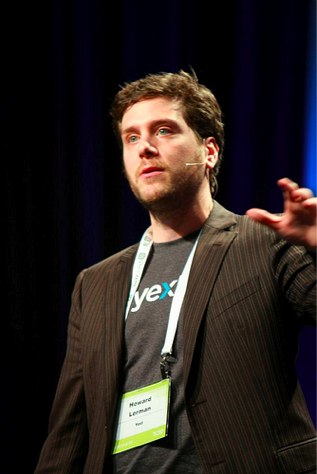

It’s just over two years since Yext debuted on the New York Stock Exchange, and to mark the occasion, I sat down with co-founder and CEO Howard Lerman for an interview.

As Lerman noted, Yext — which allows businesses to manage their profiles and information across a wide variety of online services — actually presented onstage at the TechCrunch 50 conference back in 2009. Now, it boasts a market capitalization of nearly $2.3 billion, and it just revealed plans to take over a nine-floor building in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, turning it into Yext’s global headquarters.

My interview with Lerman actually came before the announcement, though he managed to drop in a few veiled hints about the company making a big move in real estate.

More concretely, we talked about how Lerman’s management style has evolved from scrappy startup founder to a public company CEO — he described holding five-minute meetings with every Yext employee as “one of the best management techniques” he’s ever adopted.

Lerman also argued that as online misinformation has become a big issue, Yext has only become more important: “Our founding principle is that the ultimate authority on how many calories are in a Big Mac is McDonald’s. The ultimate authority on where Burger King is open is Burger King.”

Vowing that he will remain CEO of Yext for “as long as this board will have me,” Lerman ended our conversation with a passionate defense of the idea that “a company is the ultimate vehicle in America to effect good in the world.”

You can read a transcript of our conversation below, edited and condensed for clarity.

TechCrunch: To start with a really broad question, how do you think Yext is different now than it was two years ago?

Howard Lerman: One of the things that’s defined Yext over the years is our continuous willingness to reinvent ourselves. You started covering us in 2009 [at] TechCrunch 50, we were a launch company there.

And here we are now. One of the cool things about being public is: It’s a total gamechanger. It’s a gamechanger not just for access to capital, but it’s particularly important in global markets. And I’m not talking about capital markets, I’m talking about the markets in which we sell software. We have offices now from Berlin to Shanghai.

When you’re public two things happen: One is that we’re able to have a lot more credibility … and when big Global 2000 companies look at your financial reports, they can feel comfortable. You’re not going to sign a big bank in Germany without [that] credibility behind you.

But the other thing is from a compensation perspective, if you do well, you’re able to really attract amazing talent. When you look at our talent deck, in the past two years, we’ve added the president of Salesforce, Jim Steele. We’ve added Dave Rudnisky, who is the former head of North American sales from Salesforce. The talent we’ve been able to attract as a public company, it’s different than what we had when we were a one-room schoolhouse on the Upper West Side, as a scraggly group of guys in ponytails.

TC: How much have the product and technology evolved?

HL: It’s funny because when we started the company 10 years ago, people were using Citysearch and Yahoo and Mapquest. And so we had this crazy idea to update and sync information across different endpoints to control it.

The world has changed in the last 10 years, and now people use Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant. But the core idea of Yext — being able to have unstructured content, to structure it into a brain-type platform where all the content is in a database that is structured and can be understood and give answers — is the same. When you come back in 10 years and we’re in a tower, then the publisher ecosystem is going to be different again. It’s going to be AI and self-driving cars and all kinds of other forward-looking stuff.

But the big thing that has become clear is, the most important function of the internet is search. Search is king. And social, I think, has tons of eyeballs and is really important, but Twitter has challenges, Facebook has challenges, we live in an era of too much information. Fake news, people tweeting all kinds of craziness — user generated content, I think, is kind of tyranny. Anybody that has a connection to the internet can post anything they want and seem authoritative.

At the end of the day, our founding principle is that the ultimate authority on how many calories are in a Big Mac is McDonald’s. The ultimate authority on where Burger King is open is Burger King. The ultimate authority on whether a doctor treats lymphoma and accepts Cigna insurance is the hospital that they’re affiliated with. If Comic Book Guy from “The Simpsons” is in his basement and writes a post that’s false, that’s fakeness.

In the world of chaos, with all these different answers out there, what we want to bring is some verification to that, this idea of brand-verified answers. We want to be synonymous with trust, truth, with information from the source itself.

TC: To do that, are you working pretty closely with all these different platforms to make sure that when you push answers to them, that it’s treated in a prioritized way?

HL: That’s exactly right. Every search engine, from Alexa to Google to Baidu, they all crawl the web and they try to make sense of it, and that’s one layer of content. Another layer of content is user-generated content. Another layer of content are like feeds from third-party sources, like GrubHub.

Another layer of content, which we think is the most important, is the content from the business itself. That’s where Yext comes in. In all their algorithms, the best platforms prioritize first-party content over third-party content.

There’s a famous quote from Eric Schmidt, “Brands aren’t the problem, they’re the solution.” [The exact quote is: “Brands are the solution, not the problem.”] I do believe that a company like Campbell’s Soup has a vested interest in making sure that when someone says, “What are the gluten-free soups that Campbell’s has?” in Google, Google has the right answer. Because if it’s not from them, it’s from someone else, and if you eat a soup that has gluten and you’re gluten-free, you’re going to be mad at Campbell’s, not Google.

TC: One of the ways in which things have changed, I would imagine, is when you talk about Alexa or Siri or even the way Google looks now versus 10 years ago, the first result is all that anyone cares about. That primacy becomes more important.

HL: That’s particularly the case in voice search. There’s one question and one answer.

I also think search is fundamentally changing. I think we’re seeing a paradigm shift from blue links to answers, and the consumer expectation is that they’re going to get an answer when they ask a question.

But I think today, brands aren’t able to answer a lot of questions that people ask and it’s kind of incumbent upon Yext to make sure that a brand can do that. Not just, by the way, on a third-party search engine like Google or Alexa, but I see big opportunities to help brands with their own search party experience.

So to your question about some of the new things that we’ve gotten into since the IPO, if you go and look up where the nearest Burger King is on their store locator, Yext powers that experience. That’s a search experience, it’s a first-party search experience. We see big opportunities to help brands structure all their content and then give them the ability to answer questions about that content. And it could be items about menus, it could be items about where the nearest ATM for Chase bank is, if you go looking for a car, I want to find a used car dealer with a certain luxury retail brand that has the exact car that I have — that’s what we’re trying to do with Yext.

TC: How has the way you lead the company changed? Do you feel like you have to think about the business in a different way when you’ve got these quarterly earnings reports?

HL: I intend to take this company as long as this board will have me, the touchdown distance. So let me just start this off by giving you a forward-looking statement — which is something I’ve learned to say — we continue to believe we’re going to be a very big company, and we’re only a tiny fraction as big as we’re going to be. Our [total addressable market] is more than $10 billion. There’s enormous opportunity — we’re a winner-take-all, or winner-take-most company. The world needs Yext.

All the other SaaS companies are kind of boring! It’s back-office, cloud crap that everyone still hates. It’s billing, it’s identity management, it’s expense management. One of the cool things is, we affect consumers at the end of the day. The information that we collect from our customers is apparent for a huge percent of searches that people make.

Now, to your questions about the changes you have to make, there’s a great book I love. Have you read “Mindset” by Carol Dweck?

TC: I have not.

HL: So, the concept is certain people are fixed mindset and certain people are growth mindset. Certain people figure out that your mind is like a muscle and you can make adjustments and improve, like you can lift weights and get bigger muscles.

Along the way with Yext, I’ve had to make adjustments, and it’s not like the IPO was some event where it was like I was going, going, going and then I made an adjustment and now we’re doing that. In fact, I’ve made adjustments as a leader probably six times since we started. The first time was when we were 150 people — that’s the maximum size where you can know everybody’s name.

TC: One hundred fifty is pretty impressive already.

HL: When you’re a founder, you know everyone’s name for a while. And it’s a weird feeling to go from knowing everything and everybody, to not knowing anything and not knowing anybody. Now, we have more than 1,000 people around the world, we’re trying to get to 3,000 people in a number of years. I can’t operate the same.

The joke is, I spend all my time on recruiting and EQ stuff. It’s all about getting the right people doing stuff, as opposed to designing the color of a button. I remember I used to spend hours trying to get a user interface element a certain color, I’d spend days on this one thing. Now I don’t even know how to open my computer anymore.

So the skills you use as an entrepreneur change a ton, and it’s incumbent upon the CEO to make those changes if you want to go the distance. There is a path where certain founding CEOs kind step back and you bring in a more professional operator. What I did was, and this is one path, I wanted to continue to run the company but I brought in Jim Steele and Steve Cakebread who ran Salesforce with Marc Benioff, and they’re professional operators at scale. But Steve doesn’t want my job, and I don’t think Jim does either. Between that sort of crew, I’ve been able to learn from the professional operators that have built multi-billion dollar revenue business but still have a feeling that I ran the company.

God, this make me think of The Beach Boys’ dad, who they ended up giving a fake mixing board to. He wanted to mix all their songs, and he was so annoying, they gave him a mixing board that didn’t work. So he thought he did it, you know? Maybe that’s what it’s like.

Yext Inc. CEO Howard Lerman (C) rings the opening bell to celebrate his company’s IPO, at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in New York, U.S., April 13, 2017. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid

TC: When I think of you, I think of you on-stage at Disrupt, arms outspread, filled with this slightly crazy, visionary fervor. Obviously, you’ve still got a lot of the energy and passion that you had, but how do you find the balance between the startup mentality Howard versus the guy who’s leading the thousand-person team?

HL: There are certain things that you have to do letter of the law. We have our earnings reports, we have our earnings calls. I can’t give you any guidance or information about what our financials look like. So you have to be very guarded about that stuff, and that’s an adjustment, but it’s kind of easy to not talk about the numbers.

The one thing that was funny, when you go public, you go on the roadshow, you meet with everybody, the roadshow is crazy, it’s a two-week, three-week thing, you do 10 meetings in a day, lunches, dinners, you’re pitching the company until you can’t talk anymore at night, and then you do it again the next day. The only difference between that and the prior rounds of venture funding is that for the very first time, if the venture guy doesn’t like you, he doesn’t invest in your company, she doesn’t invest in your company, it’s fine. You move on. But in the public markets, people are looking to bet for you, but they can also bet against you. So you have to just realize, “Gosh, are they looking to believe in us and buy our stock, or are they looking to not believe in us and drive the price down?”

The other thing I’ll say, the investors are better at numbers in many cases than you are. I’m a product founder, numbers aren’t my super strong strength, but these guys can see things in your numbers that you didn’t even see, sometimes. You say, “Hey, let’s see the big picture here, because it’s not just about the quarterly results and some infinitesimal change and archaic accounting thing.”

That’s another thing: Startup Howard, with his hair at Disrupt, waving his hands around, used to fight every battle. I would fight every battle. I’d fight with every user on Twitter who said they didn’t like what we did. Now, I fight big battles and we’ve got teams that can do that.

The coolest thing of all is that I stand before you, a decade later, more emboldened, more confident that this original, very simple idea of one place to control your information everywhere — including on your experiences too, first party — that that single idea of moving from unstructured to structured data, in the world of AI, in the world of Alexa, voice search, self-driving cars, is more powerful than ever, and we’ve still only achieved a small fraction of what we’re going to be.

So I would say that now my job as public company CEO is number one, to have a vision, and to know concretely what we’re going to do. And then number two, you’ve gotta spend all your time communicating that vision. And it’s kind of a funny thing, because communication, it’s all about storytelling. People don’t remember facts, concepts, but if I were to tell you a story, then you remember that story.

One of the techniques I’ve developed is, I don’t believe in org charts. I started drawing an org chart as a circle, it’s just less rigid. And everyone made fun of me about this.

TC: Because then there are a lot more people touching you [organizationally].

HL: Exactly. And everyone made fun of me for this until I one-day Googled “Disney org chart,” and Walt Disney used to do an org wheel too. So whenever people make fun of me, I just say, this is what he drew.

The other thing I do, it’s called Teddy Roosevelt meetings. Teddy Roosevelt was iconic. Incredibly productive, he died when he was 53, but he squeezed 80 years into 53 years. He was a Rough Rider charging up the hill, set up all the national parks, he was a huge conservationist. And one of the things that he did was — and I saw this in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book — he set meetings with people for five minutes. And he would have 50 minutes in a row, and they’d all be meetings, and he’d have an assistant time it. You’d make your case, he’d make the decision.

And I originally read that and was like, that’s crazy, what can you do in five minutes? But then I [thought], “Well, wait a minute, if he can do it, I can give this a whirl.” It turns out giving a five-minute meeting is one of the best management techniques I’ve ever done. And what I do is, it’s non-optional, I fly to our office in Berlin, we have a hundred or so people in Germany, and I’ll meet with everyone in the office.

Five minutes is a lot of time. People get to the point. You know this, because you’re a writer — people read the headlines. So I get the headlines from 100 people, they get the audience, and at the end of the day, I’ve got a lot of new perspective and I can make adjustments and stuff like that.

TC: Do you ever have that in the New York office?

HL: Yes.

TC: But not all at once.

HL: No, what we’ll do is pick a department and we’ll do one per week. It might sound like, oh, that’s a lot. But it turns out 5,000 minutes in a year is 83 hours and we work, like, 2,500 hours. So it’s a small percentage.

TC: Changing the subject, you said that this is potentially a winner-take-all or winner-take-most market. What are the biggest obstacles that you worry about in terms of getting to the point where you’re dominating the space?

HL: Chick-fil-A is a hilarious company in a lot of ways, the founder was very eccentric with a lot of viewpoints. I read this book by him and it occurred to me that the way that Chick-fil-A grew revenue was — they make the highest amount of revenue of any QSR in the world. The average Chick-fil-A grosses about $3 million per year, and the average McDonald’s, which is second, is like $2 million. They’re like the standard.

The way Chick-fil-A grows is by opening new locations. “Okay, we’re going to open a new location in Albany, New York, boom, it’s going to be like $3 million a year.” They can’t open a thousand overnight, but that’s their path to growth. And our path to growth — because every business on the planet, every business that has a website today, is going to need to have a structured set of answers, what we call a brain, to be able to just answer questions — the way that we’re going to grow is kind of similar to how Chick-fil-A is going to grow.

For Yext, our path to growth, the model that you do it, is simply opening up the next Chick-fil-A in Albany by hiring a sales rep in Albany that can cover the accounts in that area. We are tremendously underserved around the world.

I think in our Q4 results, we said we had 170 quota-carrying reps. The best companies in SaaS, 20 percent of their headcount is quota-carrying reps, so when you think about where we want to be, we want to hire a lot more. That’s what keeps me up at night, is hiring them.

I feel really confident that the products that we have can take us to great heights. And by the way, in the data-powered future, data will be the currency. And we also said this in Q4, we have 175 million facts in Yext. The number of calories in a Whopper, that would be a fact. I see a future where you add that up, we’re in the billions and tens of billions of facts and we can become a really important part of the global internet ecosystem.

TC: Changing subjects one more time. You said that you’re here until the end of the game — I forget the exact football metaphor — but is there a specific point that you want to get the company to? Do you just feel like you’re here until somebody fires you? How do you see your life playing out?

HL: Realistically, I am probably here until someone fires me. I just read “American Moonshot,” it’s a great book, it’s about putting a man on the moon. Founding a company is kind of a moonshot. And so, while what we’re doing is not putting a man on the moon, along the way you basically set big goals. The IPO was a big goal, we have a big goal right now, it’s a goal that we hope we get to in three or four years.

There’s a great quote from JP Morgan: “You run as far as you can see, and then when you get there, you run further.” [“Go as far as you can see; when you get there, you’ll be able to see farther.”] You look around and then you decide where you want to run next. We’re running to this next one, and once we get there, we’ll figure out a next one.

Yext Inc. CEO, Howard Lerman attends his company’s IPO on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) in New York, U.S., April 13, 2017. REUTERS/Brendan McDermid

TC: Part of the reason I ask is sometimes, a founder’s interest can start to diverge from being the CEO of a public company, whether that’s starting another company or doing nonprofit work. Obviously, you’ve done some side projects, but fundamentally, it sounds like you haven’t had that itch.

HL: In today’s environment, a company is the ultimate vehicle in America to effect good in the world. It used to be politics was how you do it, now it’s just gridlock and anger. When I look at my heroes, when I look at Marc Benioff, what he’s been able to take Salesforce and stand for equality, stand for sustainability, stand for all these things, I think a company is a great vehicle to do that.

I’m not saying that I want to be an activist, but I definitely think that if you have a company you can do bigger things. This vehicle is something that I tap dance to work every day, because I love it. It’s not fully-formed yet. I know what this can be, how much bigger it can be, and I want to fully form it and have an impact on the world to get the truth out there.

TC: There’s the obvious mission of Yext, which is giving businesses these tools. There’s this other thing you seem driven by, which is fighting misinformation, establishing the brand as the primary source of information. When you think about the mission and how you want to make the world a better place, are there any other components of that?

HL: Absolutely. I think of my team first. We take care of each other, we bring families together, we’re a family. Today we have 64 vice presidents in the company, and in 3.5 years I hope to have 184. Where is that going to come from? That’s going to come from people internally, it helps grow their careers.

The impact is external. The way we describe our mission is, “Perfect answers everywhere.” But our mission of getting the truth out there affects everyone here every day that can support their families, that can grow, that have careers paths.

When we’re a lot bigger than we are — that’s a forward-looking statement [laughs] — we believe we can be a lot bigger than we are, and when we get there, then we’ll even be able to have a bigger impact and get more socially involved. We have [employee resource groups] that support people of color, support LGBT communities. I think the whole stand for equality is [an] amazing [thing] that companies can do.

The power of America has always been in corporations, and they’ve gotten a bad rap lately. That’s what’s created the fundamental economy and all the standard of living and the wealth. And there has been a turn to companies taking stands on things, which I think is pretty neat. We stand for something.