The ethics of technology is not a competition. But if aliens happened to descend upon our planet right this moment, Arrival-style, demanding to speak with our top tech ethicist, Douglas Rushkoff would be a reasonable option.

Rushkoff — a prolific writer, broadcaster, and filmmaker once named by MIT as “one of the world’s ten leading intellectuals,” recently published a new book, Team Human, that certainly would be a strong contender for tech ethics ‘book of the year’ thus far. Team Human is both an intellectual history of the technologies (including social technologies) of the past millennium or two and an effective rallying cry for humanity at a time when many of us have rightly become far too cynical to stomach most rallying cries on most topics.

Douglas Rushkoff

If nothing else, you’ll see below that Rushkoff wins, hands down, the competition for most Biblical references in one of my TechCrunch interviews thus far. He ends our conversation, however, echoing Felix Adler, the late 19th-century founder of the Ethical Culture movement — Adler, like me, was essentially secular clergy — who famously said, “the place where people meet to seek the highest is holy ground.”

I don’t know if readers of this piece will have a transcendent experience reading it, secular or otherwise, but if you want to spend meaningful time with one of the world’s greatest living thinkers on technology and ethics, please proceed below.

Table of Contents

-

“Celebration of being human”

-

The collective human agenda

-

Algorithms and creativity

-

Fear, the past and pushing forward

-

Capitalism, UBI and future order

Reading time for this article is 24 minutes (6,050 words)

“Celebration of being human”

Greg Epstein: I loved Team Human and I’m excited for TechCrunch readers to learn about it. First, how would you summarize the argument?

Douglas Rushkoff: I see [the book] less as an argument than as an experience. I’m from this old fashioned author community that thinks of books less as about whatever data or information might be in them and more about what happens to you. A book is almost more like a poem or a piece of art, or a movie that takes you through an experience. The experience I’m trying to convey is celebration of being human. To reacquaint people with their essential human dignity.

But really, the book is arguing we too easily reverse the figure and ground between us and our tools, or us and our institutions. Then we end up trying to conform to them rather than have them serve us. This time out, it might be particularly dangerous since we’re empowering technologies with the ability to search out and leverage human exploits. These are powerful tools. It’s not just some advertising agency trying something and then retooling every quarter. It’s algorithms trying things and retooling in real-time to activate our brainstem and thwart our higher processes.

I feel like the book is here to help reground people, to re-acquaint you with your power and make you a little less afraid of establishing rapport with other people. To build solidarity and activate what I think is the human organism, which is a collective thing.

Rushkoff: I think the biggest favor I’m doing for people is helping them see that they’re not alone. That there are others who are feeling this way and they don’t need to be embarrassed of wanting to think about humans as having something more than utility value.

Greg: Thank you. It was that for me. It was really a refreshing read and it came at a really important moment for me. I’d spent the past decade organizing secular congregations, because I believed, and still do, that we need a renaissance of values and community in the 21st century. I didn’t believe that was going to come from religion and I wanted to provide an alternative. But ultimately I came to believe the scale of the problem is so big I couldn’t make a difference by organizing hundreds or even a couple of thousand people. That’s what led me to tech ethics, but most tech ethics seems to me to miss the big picture: the big, positive, sustainable vision for humanity’s future. Your book was the first book that, from cover to cover, made think, “Okay. Yes, there’s a way forward. There’s a way to look at this that is not impossible. It’s difficult but not impossible and I want to spread the word about this to other people.” I’m really grateful to you for that.

Douglas: Well, I’m grateful to you for that.

Greg: All right, more about the book. It’s a culminating work for you in some ways, right?

Douglas: Yeah. It’s an end cap in some ways. [But] I would look at it less as a greatest hits regurgitation of old ideas. I’ve had a career that’s had many different threads: an economics thread, a psychedelic thread, an arts thread, a thread about narrativity, a thread about the Judeo-Christian belief system and how that contrasts with earlier, more indigenous spiritual [traditions]. I’ve had a permaculture designer reality thread.

Team Human, even though it’s a much smaller book than most of them, brings those altogether in a way I really haven’t since maybe my first book, Cyberia, where I was arguing that there’s a single cultural phenomenon that was about to occur that tied together quantum physics, and chaos math, and fantasy role-playing, and hypertext, and rave, and neo-psychedelic, and Gaia hypothesis, and lucid dreaming, and brain machines — that was all part of the same movement into a designer reality. Not a virtual reality, but that we as humans were coming into awareness of our role in reality creation.

I’ve come back to that at the end of saying, ‘Okay. We just had this explosion of new technologies and modalities to allow us to realize this, and lo and behold we surrender them all to corporate capitalism.’

Instead of creating a new reality, we’re colonizing humanity for the sake of the market. And this could be it. We finally have such powerful tools that we could really end this thing at this point.

Image via Getty Images / Donald Iain Smith

Greg: What has the response to the book been, so far?

Douglas: Close to a thousand emails a day, from people who are very enthusiastic about the messages and ideas in the book. The interesting thing is that maybe 1% actually bought or read the book.

I get it. People either don’t read now or can’t read. There’s a lot of obstacles. People don’t have time and they’re stuck in the Trump media circus nightmare.

Rushkoff: If we can use these technologies and platforms for promoting a more social reality rather than a divisive one, we’re going to activate all sorts of wonderful human mechanisms, frontal lobe things like empathy and collaboration that have been paralyzed of late.

The most common reply I’ve been getting is, “Oh, right, you’re articulating what I’ve been feeling.” I think the biggest favor I’m doing for people is helping them see that they’re not alone. That there are others who are feeling this way and they don’t need to be embarrassed of wanting to think about humans as having something more than utility value.

Some people are upset. Like right now, there’s a video of me going around from Big Think; I’m being critical of universal basic income. On the one hand, I like universal basic income because I think everyone deserves to live, but I also see the structural problems with universal basic income. UBI ends up becoming a way to preserve some of the structural inequalities of capitalism. It ends up, over the long-term, just pouring more assets into the hands of the same corporations.

Greg: It can be a fig leaf, covering up the inequality that many of its fans are actually contributing to.

Douglas: Right. There’s a guy who’s just enraged, attacking me on Twitter, calling me an elitist Ivy League professor who doesn’t know anything about the poor and [I’m] like, ‘Dude, I teach at public college in Queens. I’m getting kids who are late for class because they’re trying to move the homeless shelter that their parents are in. I’m not up there.’

The collective human agenda

Greg: At the beginning of the book, you write, “It’s time we reassert the human agenda and we must do so together. Not as the individual players we have been led to imagine ourselves to be, but as the team we actually are.”

What is the human agenda? What do you see as our collective agenda that we can and should actually rally around?

Douglas: One is, at this point, the rather controversial idea that human beings deserve a place in the future. That we should at least entertain the possibility of taking an all-hands-on-deck strategy toward climate change that keeping the environment sustainable for our children and grandchildren should be a top priority. That the idea of escaping to some digital, virtual reality is really such a last resort that it shouldn’t be getting as much attention and focus right now.

I’m a fan of little Greta from Sweden. I’m shocked. When I look at what happened in Congress with this cynical shutdown of the Green New Deal and the pretense that the Green New Deal is a way for jet-setting liberal elites to extract money from the poor, which is what the American right is saying is just so preposterous. We’re so committed to these short-term, abstracted, ideological, Facebook-like trolling arguments that we see winning those arguments as more important than keeping the species around. That’s kind of a biggie.

If we can use these technologies and platforms for promoting a more social reality rather than a divisive one, we’re going to activate all sorts of wonderful human mechanisms, frontal lobe things like empathy and collaboration that have been paralyzed of late.

Greg: The one thing you said there that I slightly disagree with is that it’s “preposterous” that Republicans are mischaracterizing the Green New Deal. To me, I totally disagree with what they’re doing, but from their perspective it makes a lot of sense to do it. They’re Swiftboating the Green New Deal – intentionally creating a false narrative because it’s in their financial interest to do so. This has worked time and time again, and I think it needs to be pushed back against in every way. Just want to get that off my chest and on the record.

Anyway.

Can you say more about the experience of the human agenda, the emotions that we might associate with it. What does it feel like to be on Team Human?

For example, another interview I’ll be doing is with my friend Sasha Sagan, a writer and the daughter of Carl Sagan, along with her mother Ann Druyan, the writer and producer of Cosmos. Druyan and Carl Sagan wrote this line, from which Sasha is taking the title of her first book: “For small creatures such as we, the vastness is bearable only through love.”

What kinds of emotional experiences are you hoping people will have as part of being on Team Human?

Douglas: For me, the beginning has been just walking down the street and finding someone else is not on their phone or stuck in whatever mediated trance they might be in and you’re making eye contact with them.

Rushkoff: There’s nothing better at extraction and abstraction than digital technology. That’s what it does. Digital technology can grow exponentially. Markets can grow exponentially even if nothing in biology can.

That’s become this weird kind of game I play, walking down the street and looking for other ones. Looking for other awake people who are looking around. We find each other and we smile. It’s like I feel like I’m part of an unarticulated secret club of non-bodysnatched humans who walk around the streets of New York or wherever opportunistically striving to make eye contact with other ones. When you find one and you make eye contact and have that moment of smile …

It reminds me of what it was like when I would go to a rave party and then the next day you’d be walking around in San Francisco or New York and you’d see someone and smile. Even though you didn’t recognize them from having been there, you had this look of like, “Oh, were you just at that thing?” Maybe they were even at a different one, who knows. There was this sense of conspiracy. The feeling of conspiracy is really fun. ‘Oh my God, we’re on this team.’ Or, ‘Oh, we’re waking up.’

Image via Getty Images / AntonioGuillem

It’s that both painful but delicious feeling when your foot wakes up after it was numb, ‘look at all the sensation that’s coming up.’ It’s that … it’s being in a room of people where they take a pause just like, ‘Oh, isn’t this great that we’re all here together?’

Isn’t that … [long pause] ‘isn’t it great to be brothers together?’ (laughs) You’re a rabbi.

Greg: Yes.

Douglas: You know the kinds of things I’m…hinay ma tov u ma naiim, shevet achim gam yachad.

(Editor’s Note: Rushkoff is quoting, in Biblical Hebrew, the first verse of the Bible’s 133rd Psalm. The line, which means, “it’s so good, it’s so nice, when brothers dwell together in unity,” became a popular — and secular — folk song in 20th century Israel.)

There’s that moment, when you acknowledge the improbability of just being in a space with other conscious being just enjoying our self-awareness, it’s magical. It creates such empowerment. It’s why Martin Luther King had people sing when the cops are coming into the church to arrest them.

It’s like, you can’t arrest them then! You’re just like, “Oh my God, look at the power of the collective human being.” I feel like the more that we activate that, the less likely we are to be suckered by divisive ideologies and intentionally coercive technologies.

Greg: I’m feeling inspired.

Douglas: That’s what that song means, right?

Greg: Yes. I sing that song with young kids, actually.

Now I want to ask you about the other team. We’re actually talking on the opening day of baseball season …

Douglas: Mets!

Greg: Yankees!

(Both Douglas and Greg groan simultaneously.)

Algorithms and creativity

Greg: As I was saying: the other team. Anyway, it’s kind of a sacred day for me; unfortunately, at least with baseball, you can’t have that sacred experience without another team to be your rival, which is sort of strange for me now as I’m raising a son. I’m really trying not to emphasize competitiveness or competition with him. But I wonder, how am I going to explain sports to him, then?

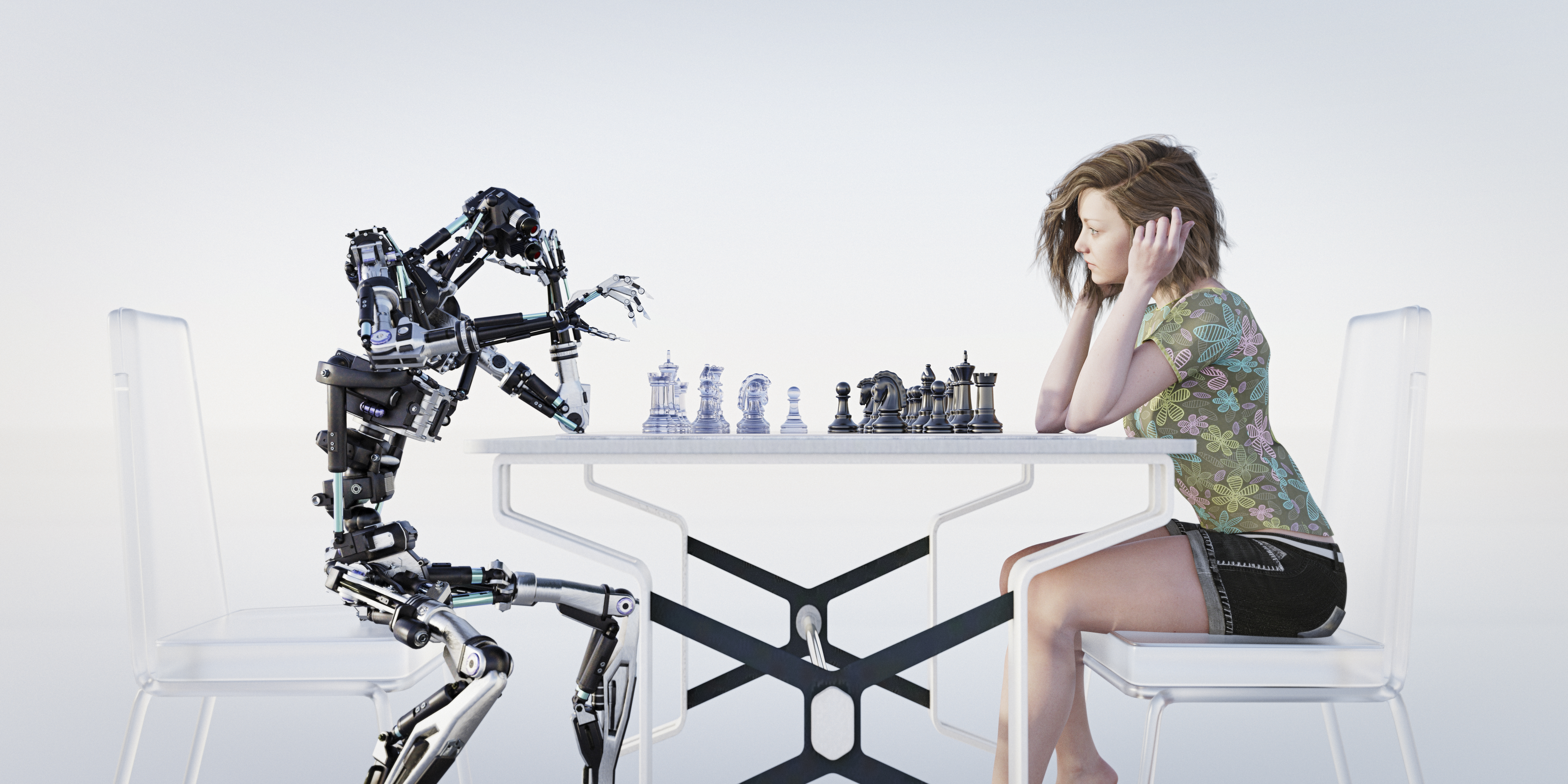

In the book you write, ‘Our most advanced technologies are not enhancing our connectivity, but thwarting it. They are replacing and devaluing our humanity, and — in many different ways — undermining our respect for one another and ourselves. Sadly, this has been by design.’

It’s the ‘by design’ I want to ask you about. What do you mean when you say this has been by design? How has Team Algorithm, or whatever it would be, actually been designing a system that thwarts our creativity for its own ends?

Douglas: I guess most simply, when digital technologies emerged, a battle ensued over who would get to establish the set and setting for this almost quasi-psychedelic journey that humanity was about to go on. And Mondo 2000 and Timothy Leary and Stewart Brand and all those people tried to frame it as an expression and expansion of the collective human imagination. Meanwhile, Wired magazine and the investment community tried to frame it as the realization of the market’s potential for exponential growth. That the Internet would be the salvation of the Nasdaq stock exchange and, in their words, allow the economy to grow exponentially forever.

And they believed it. They even got Alan Greenspan to say, ‘Yeah, I think they’re right. This may just be a new paradigm, and the market is going to keep growing unabated forever.’ And in order for the market to keep growing forever, the market that they were talking about, which is a market that, again, was devised in the year 1200 as a way of preventing the rise of the middle class, through central currency and chartered monopolies, that same economy works by colonizing things.

Rushkoff: You make sure the elders are taken care of first because they’re the elders. They’re the fossil record. They’re our wisdom bank, our memory bank. It’s interesting, in a digital age, we have outsourced memory to these machines, but we have no recollection.

And if you don’t have new continents with brown people or red people to colonize, you end up colonizing human consciousness, human civilization. Which is what they did. They used the metric for the success of an Internet website, called eyeball hours. The number of hours that human eyeballs could be stuck to the screen. They measured the site in terms of what they called their stickiness.

So we reversed the figure and the ground, the humans and the technology. We started to use technology as a way to operate humans. That has ended up bringing up to the surveillance capitalism that people like Shoshana Zuboff write about, but we’re still not looking at the root causes of it, which is an economic operating system that works through extraction and abstraction.

There’s nothing better at extraction and abstraction than digital technology. That’s what it does. Digital technology can grow exponentially. Markets can grow exponentially even if nothing in biology can.

That’s the easiest answer to the question is, that’s what they’ve initiated.

Image via Shutter_M/Shutterstock

As far as there being another team, I came up with “Team Human” and during a panel when I was being accused that I was arguing for a place for humans in the digital future out of my naïve and hubristic role as a human being. In other words, if I weren’t human, then I wouldn’t be so against machines replacing us.

That’s when I said, ‘All right, fine. I’m on Team Human. Guilty. I’m going to argue for a place for humans in the digital future rather than accepting our inevitable obsolescence and extinction.’

So, there is no other team as far as I’m concerned. The other team that folks like Ray Kurzweil are arguing for, doesn’t even exist. Technology is not alive. The digital artificial intelligence these folks want to replace us with, and I don’t just mean in the workplace, I mean existentially, they’re not alive. In that sense, they’re not real.

Greg: What do you think it is that makes a person likely to identify so much with the nonhuman?

Douglas: The book tries to explain a lot of this. When we replace circular understandings of our world, [with their concepts like] reincarnation and regeneration, with this notion of linear progress, we got some good things, like healing the earth and social justice. But there were also some negatives — basically the mindset of, ‘I’m just going to keep pushing forward and never look back. I’m going to drive my car fast enough so I never have to breathe my own exhaust.’

That notion of pedal to the metal, of, ‘I’m going to escape from everything behind me,; that includes my own body. ‘I want to live forever. I want to get out of this messy, conflicted, wet, performance anxiety-ridden existence and move into pure consciousness. I’m going to rise from the chrysalis of matter.’

And when you’re screwing people over, when you know that they’re slaves and refugees back in the carbon footprint behind you as you run forward with your iPhone and your virtual reality goggles, you’ve got to run. (Laughs.) You’ve got to run away from this reality.

And it gets to the point, like with the billionaires I’ve spoken with, where they feel so powerless to make the world a place that they would be comfortable in, that they’re investing heavily in how to escape.

It’s part of the gnostic urge. It’s part of the new age idea. It’s part of self-actualization. People are so afraid of one another, and of intimacy, and of women, and of black people, and of indigenous people, and of the harm, and the rage, that they know they’re creating behind them. It’s the way out. ‘I’m just going to go. I’m going to get out of here before this thing collapses behind me.’

Fear, the past and pushing forward

Greg: Aren’t we really just afraid of ourselves? I think we’re afraid of our own pain, our own vulnerability, our own flaws, our inability to live up to whatever we’ve been taught to expect from ourselves.

Douglas: It’s deeply psychological, for sure, but that’s always there. We read our Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death and all, but when we have multi-trillion dollar industries leveraging these innate existential fears and triggering them all the time, you end up getting weirder and weirder and more desperate behavior from people.

And that’s really what we’re seeing. In order to support advertising and capitalism and consumer targets, and when Pepsi and Coke and McDonald’s and Walmart need to grow in order to survive, they’re going to end up demanding behavior from people that can only be supported with these bizarre, negative, desperate outlooks.

The only way to get people consuming as desperately as the market needs is to create a Titanic-like situation; an every man for himself, survival-of-the-fittest panic. You know what happens when there’s going to be a hurricane, and everybody runs to the supermarket and buys all this stuff off the shelves and pushes and shoves to get it all? That’s the state they need us in constantly, in order to stoke the sorts of consumer behavior that the market needs in order to grow.

Greg: Indeed. You write, ‘We must at least provisionally believe that people of the past have something to teach us.’

Douglas: Yeah. The example I used for that was the way that people who build the Fukushima nuclear power plant ignored the markers left by the more ancient Japanese saying, ‘Don’t build anything below this slide.’ As if that’s the hubris that I’m talking about. The hubris that the past has nothing to teach us.

It seems to me that in societies where elders are no longer respected but locked away in facilities as liabilities, that we end up robbing ourselves of the wisdom they could be sharing with us. That’s insane. We’re in a society now where the 25-year-old billionaire hacker executive is considered wiser than an old person. The old person, they’ve lived longer. They’ve seen more stuff. They really are brighter.

Whereas, spend time with some Native American families. They finish [cooking] dinner and then elders get their food first. First, the elders. Then the children. Then the ‘regular people,’ the ones in the middle.

You make sure the elders are taken care of first because they’re the elders. They’re the fossil record. They’re our wisdom bank, our memory bank. It’s interesting, in a digital age, we have outsourced memory to these machines, but we have no recollection. Not to get political, but it’s like we can’t even remember that the Holocaust happened or how Fascism occurs. That’s just gone. It’s not that long ago.

I mean, I like to play this weird game. It’s like us, from our moment to the Talking Heads is more time than from the Talking Heads to Hitler. It’s a little scary.

Greg: I play that game all the time.

Douglas: As a civilization, we forget. We forget the mutual aid that happened in the depression. We forget everything but from 1999 to the present and that’s just … It’s kind of nuts.

Greg: It started with something laudable, right? Baby boomers had good reasons to push back against the strictness and the traditional morality and the racism and the sexism and repression they found, in many cases, in their parents and grandparents generations, right? Did we just go too far with that pushback?

Douglas: No. That rebellion ended up being contextualized by the advertising industry as a hatred for the people of a generation rather than an appropriate deconstruction of the operating systems that needed to be dismantled.

Another way to say it is, McDonald’s or … What’s a cooler brand? Levi’s or Volkswagen wants you to hate your parents, but not capitalism. Getting generations to hate each other: that’s great for marketing.

‘MTV is your friend. This multi-billion dollar corporation loves you more than your teachers do or your parents do.

Those parents, those teachers, they don’t want what’s best for you. Hell, they don’t even get paid a lot of money, so they must be wrong. Your parents, they don’t love you. They hate you. They’re horrible. They want to keep you from having sex and smoking pot because they don’t get to have sex and smoke pot.’

Image via Getty Images / Buena Vista Images

That’s what’s going on here.

Kids bought the idea that these brands really had their best interest at heart. ‘Right, I’m sure the people running MTV, they love me. They care about me. They want me to express who I am as a human being. My parents, they want me to suffer.’

That’s what’s happening here. The word ‘teenager’ came from marketers. They invented it because it was like, ‘Oh, wow, here’s a demographic. Here’s money that we can more easily get than their parents’ money because the parents are working too hard to spend money.’

Yeah, we lost the plot. The original critique, if you want to go back to 1968 in Paris and Guy Debord and Marcuse, was a critique of the platforms of capitalism, not your parents.

Capitalism, UBI and future order

Greg: Thank you. Let’s talk about capitalism then.

Douglas: How far back you want to go? The critique of capitalism can go anywhere. I’m glad — a lot of people understand now that growth-based capitalism is not a feature of nature. It was invented by monarchs at the end of the middle ages, to prevent the rise of the middle class.

We kept that operating system of monopoly, central currency and monopoly charters — corporations, we call them now. We kept that going for the last 500 years, so much so that even many intelligent economists don’t know this isn’t the market as nature. That this is a very particular game. It’s no more intrinsic to reality than the game of Monopoly, but we’ve grown so accustomed we just think it is.

It’s part of what makes it so hard for us to see outside band-aids for capitalism. Even universal basic income, which I’m in trouble right now for arguing against.

Greg: I’m with you.

Douglas: Even universal basic income, at its core, is a way to preserve the current inequality, not to create any structural shift.

Greg: To what extent do you have a vision for what you’d like to see in its place? For example, there’s a book that just came out by a philosopher at Yale named Martin Hägglund, arguing democratic socialism is a kind of secular spirituality. That Team Human, as its spiritual practice, should be fighting for a kind of modern, liberated socialism. What do you think?

Douglas: I don’t get into too much of … I don’t know what you would call it, economic politics or … policy recommendations. I see myself, personally, more of an anarchist-syndicalist than a socialist.

What I’m interested in now is less redistribution of the spoils of capitalism after the fact through socialism and tax policy, than a pre-distribution of the means of production before the fact. I’m really into work-our-own businesses; cooperatives and ownership.

This moving around of money after it’s been earned, it’s just like, ‘Oh, let’s tax Uber so that they pay UBI to all the masses,’ [that] doesn’t feel empowering. It feels like it creates this sort of weird, dependent state or corporate-dependent individuals.

Rather than how to deal with everything after it’s become so unequal, what structural changes can we make to encourage better distribution of assets and revenue?

One really simple one would be … Nobody is talking about this. What if we just reverse the capital gains tax with the dividends tax? Right now in America, most places, you get taxed very low on the capital gains on your stocks. If the company grows, you don’t get taxed on all that money you’ve just made, but if you earn actual money, you’re taxed really high on that.

Rushkoff: I’m not optimistic about the prospects of our human future. If I were going to play the probability game, I don’t think we make it over the next two or three centuries.

As Warren Buffet always says, “My secretary is taxed higher on her earnings than I am on my stock earnings.” What does that do? It encourages an economy where companies don’t want to make money through revenue. This is why Jack Welch said, “I’m going to earn less money making and selling a washing machine to someone than I am lending them the money to buy the washing machine.” It’s why he sold the washing machine industry.

If we have an economy that favors capitalism to the point where the person who’s lending the money makes way more money than the person who’s doing the actual work, we’re screwed. What is that about? That’s awful.

I don’t know that democratic socialism, as it is currently being articulated, looks at those sorts of structural problems. I’ve got emails into my friends at all the campaigns saying, “Yo, bring me in and I can help you articulate how we move from a growth-based economy to a flow-based economy.” Growth doesn’t have to be prerequisite for economic health.

Greg: Is there a candidate you feel is doing the best job at articulating these kinds of pro-human concerns right now?

Douglas: I haven’t picked a candidate yet. In my own politics, and as I try to model for others, I think we’ve overemphasized the one big national overarching presidential campaign, often at the expense of the local politics where so much else happens. Local politics informs federal politics.

Gosh, there’s so many opportunities for people to make real changes in the lives of their neighbors and those who are around them. If we all seize those opportunities, we’d be less dependent on the central government to do the right thing, which they don’t.

Greg: Having come out of ten years of congregation building and just seeing how much of an uphill struggle that is, you’ve re-inspired me to recognize that actually, these civic institutions that we’re building, the kind of neural network of our potential democracy, of our potential humanity, that they really are great places to meet and connect with people and feel less isolated and do creative work.

QUIQUE GARCIA / AFP / Getty Images

Douglas: A lot of people are asking me to make Team Human into a movement. I’m pushing back against that: we don’t need another movement. I see Team Human more as pollen that you can take out into the world. We are lucky enough to live in a democracy where there are school boards and local zoning meetings.

Right now, it feels like the only people who go to these meetings are weird town crazies. We could fill these spaces and make real differences, [in] our local library, in our school district, land use and our downtowns and our economic revitalization, all those sorts of things we can do. That is local government. And it’s not that …

I don’t want to say it’s not hard. It’s work, but it’s the drudgery of engaging with others and figuring out how to establish consensus with other people. We have mechanisms for that. They’re not perfect. They’re using, [for example,] Robert’s Rules of Order instead of Loomio’s consensus building tools. But even that is up for discussion.

Greg: I could see Robert’s Rules of Order as a kind of alternative to prayer. An alternative to having a liturgy. Rather than having a set liturgy of things we go to a church or synagogue or temple to say, we have tools to help conduct ourselves in conversation when we go to a public, community space.

Douglas: Right. How do you get the thing that you cared about? How do you get it on the agenda? There’s a time and there’s a space in the agenda for people to bring up items that they want on the next agenda. Then you’ve got your four minutes to stand there in front of your town and making arguments to the point where someone seconds what you’re saying. It’s politics, but it’s local politics. It’s not character assassination which is what we think as politics when it’s being carried out on a commercial, cable news media.

Greg: You’ve spent so much time teaching, and broadcasting, and sitting behind a keyboard and a screen to write all of these books. You must have times in your life where it’s hard for you to connect with other people as well.

Douglas: Sure.

Greg: When you’re struggling to connect, what helps you to reconnect with other people, with your own humanity? I mean, I am very sympathetic to your argument. I think I also have this very pro-human mentality. When I love people, I love them intensely, but I have a lot of times in my life where I come home and I’m tired. I look at my wife, who I’m supposed to love the most in the entire world, and I can’t connect. I wish I could reach out to my friends more, but I just feel like I can’t connect. You’re arguing we need to get past that somehow. What insights have you developed or what struggles have you had with that over the years?

Douglas: I think the best insight I’ve had is, and maybe it’s partly the puritan-working American mindset. Or maybe it’s the way that we try to model our technologies in terms of functionality, but when I can stop thinking about everything in terms of utility value and start looking at things in terms of essential value, then I no longer need a good excuse to call someone or be with somebody.

In other words, to send an email to someone and think, ;Oh, I’d really love to see Frank. I really like Frank. Oh, right. He’s working on a book. Hey Frank, want to get together? We can talk about your book or if there’s any advice you want,’ as if I have to offer something other than our getting together as the reason to get together.

And it’s not a self thing. People are going to think, ‘Oh, right. What I need to do is to see myself as valuable, so I could call others with a confidence that I’m worth their time.’ No no no, I’m not even saying that. I’m saying you need to reassert that two people spending a moment together in real space, two people being together is, itself, that’s the religion. That’s what makes life worth living.

‘There in the empty space between the two cherubs, that’s where I’ll come to you.’ (Editor’s Note: a Biblical reference, to Exodus 25:22). Wherever people gather, that’s where the sacred happens. The beauty of Team Human is that when you connect with another person, you are fulfilling the prime command, the core command of our species and perhaps of the evolution of reality itself.

Greg: How optimistic are you about the prospects for our human future?

Douglas: I’m not optimistic about the prospects of our human future. If I were going to play the probability game, I don’t think we make it over the next two or three centuries. I think it goes. I am hopeful people can wake up and find ways to sustain our species through compassion rather than exclusion.

Greg: Douglas Rushkoff, I hereby appoint you as one of the co-captains of Team Human.

Douglas: Oh, thank you. You could be one too. We can all be captains.

Greg: Yeah, well, I’ve got some practicing to do. I need more batting practice.

Douglas: You’ve done more team captaining than I am.

Greg: Maybe.

Douglas: I’ve been sitting alone writing books.

Greg: They’re inspiring books! Thanks again.