Ever since Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods became official in August, food tech entrepreneurs have been holding their collective breath in anticipation of what comes next. First prices dropped; now, apparently, they’re on the rise.

Without knowing Bezos’ ultimate vision for an Amazon-owned Whole Foods, food tech companies must decide whether and how to compete. I offer apprehensive entrepreneurs a cautiously optimistic message: Exhale, at least a bit. Despite the new market reality, there’s enormous opportunity to thrive.

As early investors in Starbucks, P.F. Chang’s and Jamba Juice, we’ve seen food trends come and go. Every so often we come across something more fundamental and lasting than a trend: a seismic shift. Starbucks’ visionary leader Howard Schultz helped create one such shift.

Inspired by Italy’s rich coffeehouse tradition, he taught Americans to expect better quality products and an elevated customer experience, setting us on a path towards today’s foodie frenzy.

We are currently experiencing another seismic shift, a deepened awareness that what we consume directly impacts our health and well-being and reflects our core values and aspirations.

Consumption of bottled water is now outpacing soda, and organic food sales totaled $47 billion last year, accounting for more than 5 percent of total US food sales. Amazon’s Whole Foods acquisition is a reflection of the shifting attitude towards food. The good news is that despite Amazon’s looming presence, there’s plenty of opportunity to be found.

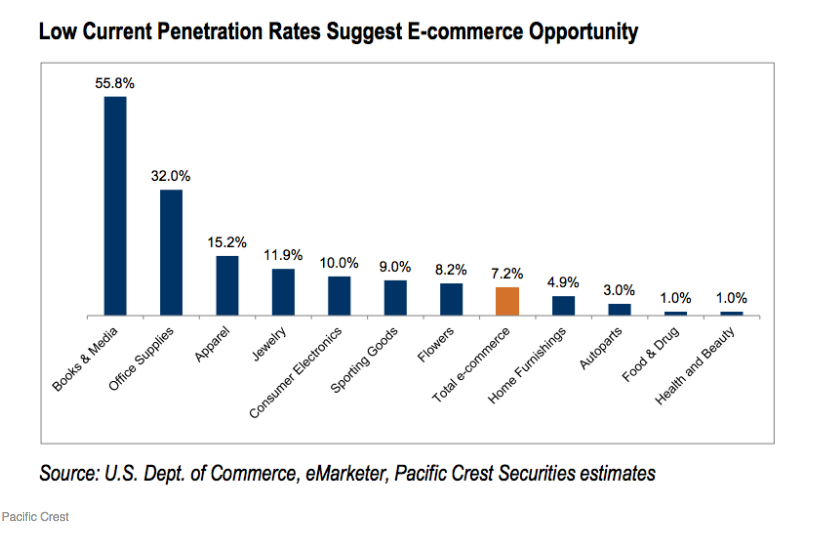

Each year Americans spend a colossal $1.4 trillion on food. This breaks out to $800M on restaurants (including delivery) and $600M on grocery sales. Though Amazon dominates ecommerce with 43 percent of all online sales in 2016 and evenhad an 18 percent share of online food sales before the Whole Foods acquisition closed, groceries have achieved only a measly 1% online penetration rate. That leaves tremendous opportunity for growth.

The grocery channel’s low online penetration rate can be attributed to daunting logistics, from sourcing, prepping, and packaging to the distribution of perishable consumables. Despite the logistical challenges, food’s massive market size and the online growth opportunity can enable companies capturing even a small piece of the pie (pun intended) to become huge successes.

More than any company in the world, Amazon has successfully brought new retail categories online and solved highly complex logistics challenges in the process. They will use the Whole Foods acquisition to drive more food sales online, using Whole Foods locations as distribution and delivery centers in order to mitigate many of the aforementioned challenges.

Operations and distribution are Amazon’s core strengths; their acquisition of Whole Foods will fortify those competitive advantages as they move aggressively into grocery sales. Operations and distribution are also core competencies of numerous well-funded private food delivery companies, such as UberEATS, DoorDash, Instacart and Postmates. It’s a daunting competitive landscape to say the least.

That said, operations and distribution form only two pieces of the food tech puzzle. While competing against Amazon and other well-funded companies in their areas of strength is generally ill-advised, companies can flourish by focusing on one or more dimensions outside their “sweet spot”:

- Aspirational brands – Great CPG brands become iconic by reflecting not necessarily who we are but what we aspire to be. Today, many consumers aspire to improve their health and wellness. Recognizing this shift, large companies like Pepsi are investing in health-conscious brands to generate strong sales and outpace competitors. The shift is also creating significant opportunities for new brands, some of which will become tantalizing acquisition targets, such Bai antioxidant drink, acquired by Dr. Pepper Snapple for $1.7 billion.

Brands that authentically embody multiple aspirations may be especially well-positioned. Bevi (one of our investments) appeals to customers who care about both health and sustainability. Their smart water cooler dispenses flavored still and sparkling water beverages while reducing plastic and aluminum waste and saving customers money.

Busy parents often seek to both serve healthy food and to prepare it efficiently. Just look at the viral sensation of the Instant Pot, which has achieved acult-like status among that demographic. As another example, the meal kit company Gobble, which enables busy parents to prepare healthy dinners in 15 minutes, just closed a $15 million Series B investment led by Khosla Ventures (Andreessen Horowitz, Initialized Capital and Trinity Ventures also participated) — despite both Blue Apron’s shaky stock performance and Amazon’s entrance into the market.

- Proprietary food products– Growing consumer demand for healthy and sustainable food options has fueled research into nutrition and food science. Advancements coming out of this research have led to food-related patents which, by definition, are defensible against competitors. Impossible Foods, which has raised nearly $300 million from Bill Gates and The Open Philanthropy Project, among others, has invented an environmentally-friendly soy-based product which looks, smells, tastes and even “bleeds” so similarly to ground beef that it has been incorporated onto the menus of numerous celebrated restaurants. Our portfolio company Bulletproof has created proprietary “biohacking” products, such as mycotoxin-free coffeeand collagen bars, to help consumers improve their mental and physical performance. While Amazon sells many Bulletproof goods, and may sell Impossible Foods products someday, it’s highly unlikely that it would ever try to replicate the offerings to compete directly.

- Specialized market segments – Amazon does an exceptional job of appealing to the masses, but given the food market’s enormous size, companies that focus maniacally on particular segments can still carve out large and highly profitable businesses.

One defensible segment involves the institutional market. (In this context, “institutions” refer to companies, schools, hospitals, hotels or other establishments that provide or sell food and beverages to consumers.

This business model is also known as “B2B2C.”) EAT Club (a Trinity investment) provides a cafeteria replacement solution to small and mid-sized locations, enabling employees to order meals for daily delivery. By selling through employers, B2B2C companies reach many end-consumers and enjoy reliable, recurring revenue streams (similar to a subscription model).

Similarly, Revolution Foods delivers healthy school lunches to millions of children and was set to reach $150 million in sales last year. By serving such specialized segments, these companies build up natural competitive buffers, such as tailored hardware and software and proprietary logistics, workflow and distribution systems.

At first blush, Amazon’s Whole Foods acquisition might appear to sound the death knell for food tech entrepreneurship. Yet when Howard Schultz introduced the world to Starbucks, coffee looked like a commodity, and coffee houses looked like local niche offerings.

Today’s food tech landscape has its land mines, but the outlook is rosy for entrepreneurs who can navigate through them. I can’t wait to see the (nutritious and sustainable) trails they blaze.