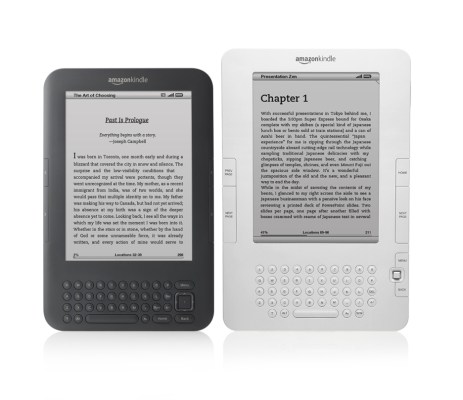

Next month marks 10 years since the first Kindle debuted. It’s a virtual lifetime in consumer electronics terms, but compared to its mobile brethren, e-readers’ pace of innovation has been glacial. Front lighting for night reading and waterproofing have been heralded as major upgrades, but beyond that, little about the space has changed. The core of the product has remained largely unchanged, down to the basic e-ink screen that’s the centerpiece of practically every one of these devices.

Why has the e-reader stagnated? Demand has played a role, certainly. Analysts just don’t keep stats the way they used to, but most agree that demand for devoted e-readers peaked around 2011 — though the longstanding declarations of their death have been ringing out since well before then, with most pointing the finger at the rise of low-cost tablets. The fact that all the big e-reader manufacturers also make a mobile app has likely also helped ease that transition.

There was bound to be market contraction regardless. In an age where a smartphone serves as everything from a dating tool to a health monitor, it’s become increasingly difficult to market a device that’s really only built to do one thing. And that’s resulted in a pretty significant thinning of the herd. Barnes & Noble’s Nook reader exists in name only at this point, and Sony threw in the towel a few years back.

There are a number of readers with a bigger presence outside the States. French company Bookeen sent me an email earlier today to remind me of their existence (and the fact that they’ve just launched a “revolutionary” new reader) and the fact that they’re apparently huge in Brazil. In the U.S., Amazon runs the show. Kindle has become synonymous with e-reader for most mainstream users. It’s not quite a monopoly, sure, but the company’s utter domination of the American market is the sort of thing that tends to slow innovation.

Case in point: Kobo. Now owned by Japanese retail powerhouse Rakuten, the company mostly flies under the radar here in the States. It’s a shame, really, as the company has been one of the primary innovating forces in the category in recent years, experimenting with different screen sizes, premium readers and introducing a waterproof model years in advance of yesterday’s Oasis announcement.

And certain additions like expandable memory and additional file formats will likely never come to the Kindle, as they detract from the company’s core model of selling content through its own store. Kobo’s longtime embrace of the ePub format is one of the things that’s kept me coming back to the company.

An even larger roadblock is the nature of the space itself. E-readers are, by their nature, feature-limited. Each subsequent generation is likely a battle between what to include and what to leave off. In a sense, these devices are defined as much by what they’re not. Once functionality starts infringing on the smartphone, you begin to lose sight of the key focus: an unfettered and undisturbed reading experience. Every superfluous notification detracts from that goal.

Ten years after the first Kindle, e-ink remains the best technology for the devoted e-reader. It’s easier on the eyes than an LCD, is readable in daylight and gets stupid-long battery life — these devices routinely boast between six weeks and two months, an unparalleled feat among consumer electronics devices. But the technology hasn’t evolved all that much in over a decade. Refresh rates are still a major hurdle to doing anything beyond page flipping.

Color e-ink, meanwhile, has seemed perpetually just out of reach. Technologies are just too expensive, too glitchy or both. And besides, a move to color brings us back to that earlier question: at what point would users just be better off with an inexpensive tablet? As an avid comics reader and frequent e-reader user, the idea of trying to marry the two is downright headache-inducing. Even comics like Manga, designed to be read in black and white, are much better served on an inexpensive tablet. The screen size and refresh rate do a disservice to reading anything but straight-up text.

Rumors of the e-reader’s death have, as they say, been greatly exaggerated, but for those who follow the consumer electronics industry as a whole, progress has slowed. And barring some combination of a massive reversal in popularity, huge technological breakthrough and reintroduction of competition, it’s hard to imagine that changing any time soon.

That lack of major evolution year over year is likely contributing even further to a decline in sales. As with tablets, people are comfortable hanging onto their readers for a number of years, while the relative lack of new features makes upgrades even less compelling. But the simple truth is, as long as it keeps selling those users new e-books, Amazon doesn’t really mind all that much.