The hope of tech-industry optimists for what former AOL chief and Revolution LLC founder Steve Case calls “the rise of the rest” — the spread of tech into the heartland — has gotten more urgent. With Donald Trump’s election reflecting an angry backlash against high-skill elites, many tech people are hoping the growth of tech jobs in “flyover country” will help tamp down raw feelings by allowing struggling Main Street communities to participate more fully in tech.

Some tech executives — provoked by Trump’s proposed travel bans and potential limits on H-1B visas — are even getting political, and wondering if some of their firms’ job creation can be strategically directed into Main Street cities to ease tensions and even flip the Electoral College.

However, there’s a problem here: A quick look at recent data from Brookings on tech-sector employment does not license a ton of optimism for any widespread knitting of the country back together through the location dynamics of tech.

In fact, a close look at job-creation in four key digital services industries — software publishing, data processing and hosting, computer systems design and web publishing/search — finds that while tech employment is growing all over America, it really isn’t “spreading out” in terms of cities’ share shifts. Instead, the tech-employment “rich” — namely San Francisco and San Jose — are getting richer. Agglomeration economies are everything.

Nationally, to be sure, these industries are stars. Taken together, these dynamic digital industries generated more than half of the country’s high-quality new “advanced industries” jobs between 2013 and 2015. Moreover, notwithstanding worries about a “jobless recovery,” employment growth in the sector has exploded in recent years, propelled by social media, virtual reality and artificial intelligence booms — to the point that employment in the sector has been growing by 5.5 to 6 percent a year at a time when the economy as a whole has been growing by less than 2 percent a year.

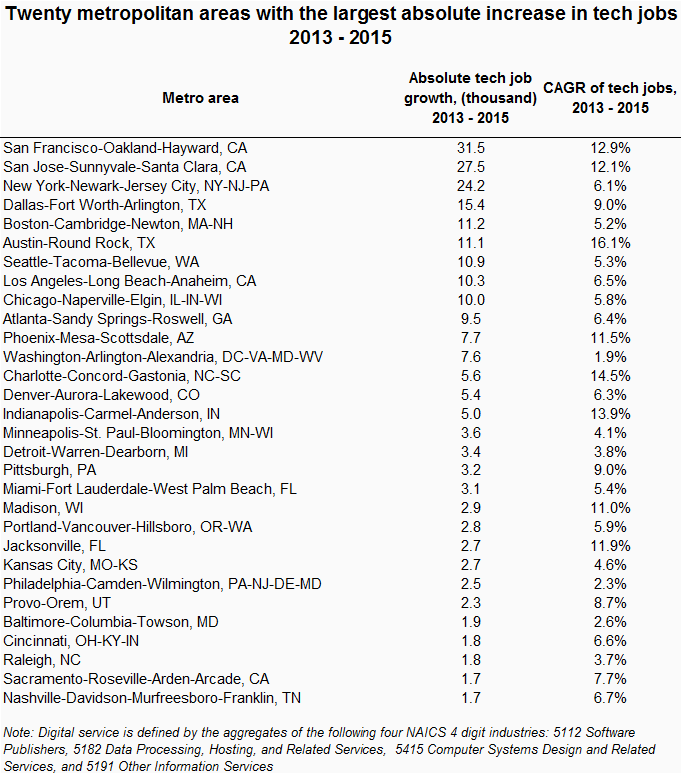

Nor is the action entirely confined to the coastal meccas. Far from the Bay Area lie exciting hot spots in regular America. Cities like Dallas, Phoenix and Indianapolis are coming into their own, with Dallas adding 15,000 tech jobs in the last two years, Phoenix nearly 8,000, and Indy nearly 5,000, as each city grew its tech employment by more than 9, 11.5 and 13.9 percent a year, respectively. University towns like Madison, Provo and Raleigh are also hot with tech-job growth rates of 11, 8.7 and 3.7 percent CAGR a year, respectively. And there are consequential, growing digital scenes in places like Chicago, Washington, Pittsburgh, Kansas City and Nashville.

Source: Brookings analysis of Moody’s Analytics data

Given these developments, the digital services sector represents the heart of the U.S. tech boom, with its promise of stimulating more and more inland towns with cool and good-paying new jobs with long multipliers.

And yet, here’s the thing: Notwithstanding the fact that tech is spreading, with more cities participating, tech is in fact polarizing. Even as it diffuses, somewhat, the sector is in fact continuing to concentrate into a short list of the nation’s densest tech hubs.

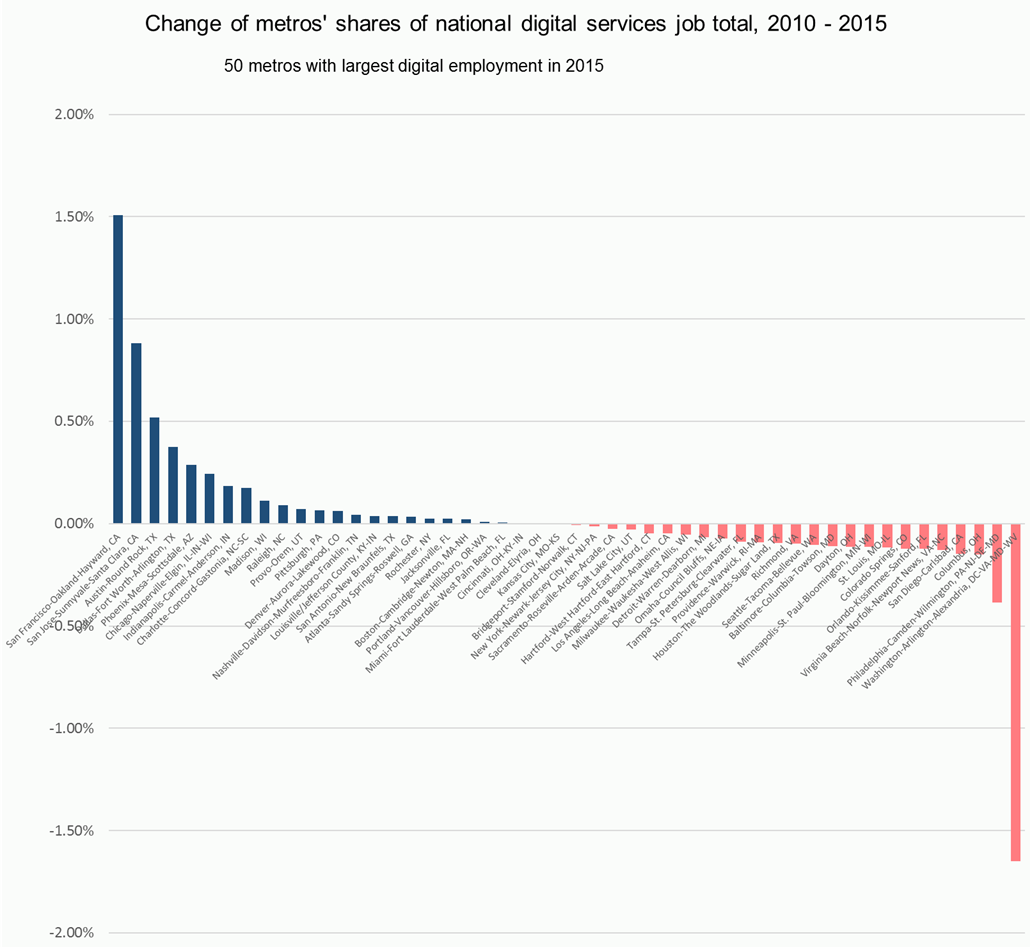

In this regard, what is striking is not just that a whopping 46 percent of all U.S. digital services jobs cluster in just 10 of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas (ranging from New York and Washington to San Francisco and San Jose to Boston, Seattle and Atlanta) — even more striking is the fact that only a handful of metropolitan areas have significantly increased their share of the nations’ digital services jobs since 2010.

To be specific, just five metropolitan areas out of the nation’s 100 largest — San Francisco, San Jose, Austin, Dallas and Phoenix — accounted for nearly 28 percent of the nation’s 2010-2015 tech growth, and, in doing so, have measurably increased their share of the nation’s tech job base.

In this regard, a whopping 17 percent of the nation’s post-crisis job-creation in tech took place not in emerging, inland places, but in San Francisco and San Jose — the same established locations that have dominated the industry for decades. San Francisco added almost one-tenth (67,000) of the entire nation’s new digital services jobs in the period, increasing its share of the national sector by 1.5 percent. San Jose added more than 51,000 new digital services jobs (7.6 percent of the nation’s total) in the period, increasing its share of the sector by 0.9 percent. Together, the Bay Area hubs now encompass 10 percent of the nation’s digital services employment, up from 9 percent in 2013 and 7.7 percent in 2010.

By contrast, 61 of the nation’s largest 100 metropolitan areas have either seen their share of the national sector go sideways or actually shrink since 2010 — and six of them actually lost jobs in absolute terms.

The result: Most tech jobs are being created in the Bay Area and a very few other core tech hubs — far from the troubled locales that need them most. The upshot: Tech is divergent, not convergent. Tech is still growing increasingly concentrated in a few prospering metropolitan areas while the rest of the country drifts.

As to what these patterns say about the nation’s fissured political economy, the heightened dominance of the digital services core cities underscores how predominant is the pulling-apart trend in the economy — and how difficult it will be to reverse it. In this respect, the digital services element of the larger tech story reflects a broader national story.

America’s bifurcating economic map displays growing differences, not just between people, but between communities. In many respects that polarized map is a geographic expression of the “skill-biased tech change” that economists like David Autor et al. say favors skilled over unskilled labor in the labor market. But at any rate, the current national economy heavily favors — as explains Enrico Moretti, another economist — a handful of cities with the “right” industries and deep pools of well-educated workers who can compete for jobs with high wages.

Meanwhile, those cities at the other extreme, the ones with the “wrong industries and a limited human capital base,” are stuck with dead-end jobs and low average wages. The divide is what Moretti calls the Great Divergence, and it is exacerbating not just the nation’s economic fissures, but all other differences. That the knowledge economy has an “inherent tendency” toward geographic agglomeration, as Moretti puts it, makes all of this more challenging, because “initial advantages matter, and the future depends heavily on the past.” In other words, strong regions get stronger.

And yet, for all of that, it seems important to hold open a little space for change, despite the deterministic trends.

The arrival, for example, of cloud-based tools for entrepreneurs and consequential startups run by laptop adds meaningfully to Steve Case’s conviction that high-growth companies can now start and scale anywhere, and not just in a few coastal cities. Likewise, the spread into “flyover country” of the computer systems design portion of the digital services sector out of its core creative hubs shows a welcome diffusion of significant tech employment into scores of Main Street cities, large and small. Beyond that, there remain the inspiring stories of Rust Belt revival told by Antoine van Agtmael and Fred Bakker in their book The Smartest Places on Earth.

Finally, if the Bay Area’s big tech firms want things to go differently, they can always make it so. Specifically, they can “weaponize” their own sizable job creation, as one executive told me, by distributing some of it to some of the nation’s other aspiring cities. In short, by “leaning in” and directing some of their growth toward Main Street, Bay Area tech companies might make a down payment on a new narrative and a more balanced and healthy geography of tech.

And so, while the strongest cities are getting stronger, and almost all others are “muddling along,” as Bloomberg View columnist Justin Fox has reflected, it doesn’t have to be that way. Maybe it’s time for tech people to do more to make the “rise of the rest” a reality.