A security issue has been flagged in the hugely popular mobile messaging app WhatsApp that could allow for messages sent via the encrypted platform to be intercepted and read.

The Guardian report, which describes the vulnerability as a “backdoor”, notes that independent security researcher Tobias Boelter identified the issue in April 2016, when he says he reported it to Facebook, only to be told it was “expected behavior”, and that the company was not actively working on fixing it. The newspaper says it has verified the vulnerability still exists.

Despite being a mainstream messaging app, WhatsApp has gained praise from security experts for implementing the respected end-to-end encryption Signal Protocol across its platform — completing its roll out of end-to-end encryption in April last year. Yet the company’s code remains closed source, which means users have always been required to trust its claims with no ability for external audits of its code (although it’s also worth noting that WhatsApp did work with Open Whisper Systems (OWS), the organization behind the Signal Protocol, to implement the e2e crypto across the platform).

The security issue identified by Boelter, and reported on by the Guardian now following him giving a talk about it at the end of last month, concerns an aspect of WhatsApp’s Signal implementation that allows it to force the generation of new encryption keys for offline users. This is described as a “retransmission vulnerability” by Boelter, and claimed as a route for messages to be intercepted and read — and thus as a potential backdoor in WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption.

However WhatsApp denies the backdoor characterization, saying it’s a design decision relating to message delivery, with new keys being generated for offline users in order to ensure messages don’t get lost in transit.

“The Guardian posted a story this morning claiming that an intentional design decision in WhatsApp that prevents people from losing millions of messages is a “backdoor” allowing governments to force WhatsApp to decrypt message streams. This claim is false,” said a company spokesperson in a statement sent to TechCrunch.

“WhatsApp does not give governments a “backdoor” into its systems and would fight any government request to create a backdoor. The design decision referenced in the Guardian story prevents millions of messages from being lost, and WhatsApp offers people security notifications to alert them to potential security risks. WhatsApp published a technical white paper on its encryption design, and has been transparent about the government requests it receives, publishing data about those requests in the Facebook Government Requests Report,” it added.

WhatsApp/Facebook details its responses to government requests for user data here.

Multiple security commentators have also pointed out that the vulnerability being flagged here is nothing new — but rather a rehashing of the long-standing issue of how key verification is implemented within an encrypted system.

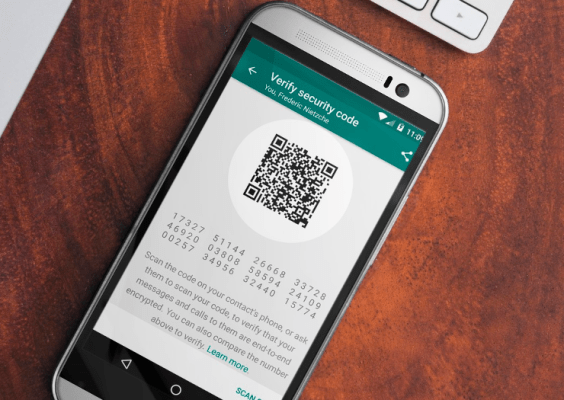

In an earlier statement WhatsApp pointed out that its implementation of the Signal protocol includes an optional “Show Security Notifications” setting that will notify a user when a contact’s security code has changed — thereby allowing users to opt in to be notified when/if a key has been changed (and thus when/if there’s a risk of their messages being man-in-the-middle intercepted).

At the time of WhatsApp completing its implementation of the Signal Protocol, OWS’ Moxie Marlinspike also explained that the implementation offers users an “opt in to a preference which notifies them every time the security code for a contact changes”.

He also pointed to a white paper on the WhatsApp Signal Protocol implementation which further states: “WhatsApp servers do not have access to the private keys of WhatsApp users, and WhatsApp users have the option to verify keys in order to ensure the integrity of their communication.”

In the same blog post Marlinspike argued that WhatsApp users would now get “all the benefits” of “a modern, open source, forward secure, strong encryption protocol for asynchronous messaging systems, designed to make end-to-end encrypted messaging as seamless as possible”. The Facebook-owned messaging platform has more than a billion monthly active users at this point.

Contacted by TechCrunch about the Guardian article, Marlinspike was clearly unimpressed with their characterization of WhatsApp’s key verification system as a security issue — describing the story as “supremely inaccurate”.

He’s since written a blog post describing the WhatsApp client as “carefully designed”, and its choice of displaying a non-blocking notification as “appropriate”, arguing: “It provides transparent and cryptographically guaranteed confidence in the privacy of a user’s communication, along with a simple user experience.”

But Katriel Cohn-Gordon, one of the group of international security researchers who audited the Signal Protocol, was less dismissive of the issue, describing the ‘bug’ flagged by Boelter as “nontrivial” — although he did not go so far as to call it as a backdoor, and also characterized the newspaper’s report as “relatively strongly worded”.

(For clarity, the researchers’ analysis of the Signal Protocol found the underlying protocol to be lacking in any logical errors — but did not study the security of the implementation of the protocol. And its WhatsApp’s implementation of Signal that people are quibbling about here.)

Whether WhatsApp’s key verification process/”nontrivial” ‘bug’ is an intentional security backdoor or a design decision with a user opt-out depends on your perspective. But arguably the platform’s biggest security flaw remains not open sourcing its code to allow for external audits — not least given that its parent company, Facebook, has a business model based on monetizing the personal information of users via profiling their preferences and targeting them with ads.

Alan Duric, co-founder and CTO at another mobile messaging app, Wire, whose end-to-end crypto, Proteus, is open sourced, wastes no time in pointing out that outsiders can test its security claims, unlike WhatsApp’s, which users rather have to take on trust. Wire is in the process of having its Proteus protocol audited by a security outsider, according to a spokesman.

“Wire does not regenerate encryption keys,” Duric tells TechCrunch. “Once the key fingerprints have been verified by users changes in keys will be detected on both ends and shown to the users. Wire is transparent in how it works and because all code is open sourced it doesn’t take 8 months to discover, disclose and fix security issues.”

“By embracing open source we are always a step ahead of situations like these as there are thousands of developers who’ve looked at our code in GitHub and many have analysed it in more depth,” he adds.

We asked Boelter for his views on whether the retransmission vulnerability was created intentionally by WhatsApp, i.e. to be a backdoor for access to data (whether for Facebook or government agencies), or is an accidental byproduct of design decisions vis-a-vis message delivery — and he argues both sides.

“If someone would demand WhatsApp to implement a backdoor, you might expect them to implement something more obvious. Like responding with the history of all conversations when triggered to so do with a certain secret message. Furthermore, this flaw can be explained as a programming bug. Just a missed “if” statement for one of the corner cases. It is a type of flaw that is not necessarily introduced by malice,” he says.

“However, Facebook showed no interest in fixing the flaw since I reported it to them in April 2016. So maybe it was a bug first, but when discovered it got started being used as a backdoor.”

“WhatsApp has stated recently that this is not a bug, it is a feature! Because now senders don’t have to press an extra ‘OK’ button in the rare case they sent a message, the receiver is offline and has a new phone when coming back online. That’s not a very good argument! And if “Privacy and Security is in [WhatsApp’s] DNA”, they should have fixed the flaw immediately after I reported it in April 2016,” he adds.

Boelter further noted that while the WhatsApp server can re-announce the “old, correct, private key of the recipient to the sender” — i.e. if the sender has opted in to receive the “Security Code has changed” notifications — the conversation can still continue “uninterruptedly”. Ergo, it relies on users both noticing and understanding the privacy risk implication of the notification, given that communication after a key has changed is not actively blocked by WhatsApp (as it is by the Signal messaging app, for example).

“WhatsApp can also opt to correctly deliver messages for a while without informing the sender that the messages have been delivered correctly. And only after a while trigger the key-switch,” he adds.

Which secure messaging app does Boelter recommend using? “I use Signal,” he says. “Signal is open source. Signal makes an effort to have reproducible builds. Signal claims to store much less metadata on their servers than WhatsApp allows itself in their privacy policy. And Signal is just as easy to use as WhatsApp.”

In his April analysis of WhatsApp’s Signal implementation, Boelter further wrote: “Proprietary closed-source crypto software is the wrong path. After all this — potentially malicious code — handles all our decrypted messages. Next time the FBI will not ask Apple but WhatsApp to ship a version of their code that will send all decrypted messages directly to the FBI.”

This report was updated with additional comment