Uber drivers are workers rather than self-employed contractors, according to a ruling by an employment tribunal in the UK.

It’s a landmark win for workers’ rights in the so-called gig economy where platform giants have sought to minimize costs by classifying the large numbers of people needed to operate their services as self-employed.

The tribunal’s ruling means Uber drivers in the UK will be entitled to holiday pay, paid rest breaks and the National Minimum Wage. Although Uber has said it will appeal.

In a statement, Jo Bertram, regional general manager of Uber in the UK, said: “Tens of thousands of people in London drive with Uber precisely because they want to be self-employed and their own boss. The overwhelming majority of drivers who use the Uber app want to keep the freedom and flexibility of being able to drive when and where they want. While the decision of this preliminary hearing only affects two people we will be appealing it.”

The ruling, which was brought by two Uber drivers (one current, one former), could also impact other gig economy startups operating in the UK, although the tribunal only considered the specific terms Uber applies.

But the judgement is likely to encourage other employment classification challenges, and could also apply pressure for regulatory clarity over the employment status of workers on tech platforms more generally.

“A pure fiction”

In this instance, Uber’s counsel had tried to argue that the company merely supplies ‘partner’ drivers with “business opportunities” but the tribunal disagreed, taking a sceptical and ultimately dim view of its arguments — including dubbing Uber’s “supposed driver/passenger contract” as “a pure fiction which bears no relation to the real dealings and relationships between the parties”.

Setting out its conclusion, the tribunal writes:

We have reached the conclusion that any driver who (a) has the App switched on, (b) is within the territory in which he is authorised to work, and (c) is able and willing to accept assignments, is, for so long as those conditions are satisfied, working for Uber under a ‘worker’ contract and a contract within each of the extended definitions.

It goes on to say it was struck by “the remarkable lengths” to which Uber has gone to try to compel agreement with its own definition of its company and the legal relationships between the various parties involved — describing it as “resorting in its documentations to fictions, twisted language and even brand new terminology” to try to advance its arguments.

“It is, in our opinion, unreal to deny that Uber is in the business as a supplier of transportation services,” it adds. “Simple common sense argues to the contrary.”

The tribunal also dismisses as “faintly ridiculous” Uber’s notion that in London its business is a “mosaic of 30,000 small businesses linked by a common ‘platform’.

“In each case, the ‘business’ consists of a man with a car seeking to make a living by driving it,” it asserts, noting that drivers are in no position to negotiate with passengers to strike a bargain. “They are offered and accept trips strictly on Uber’s terms,” it adds.

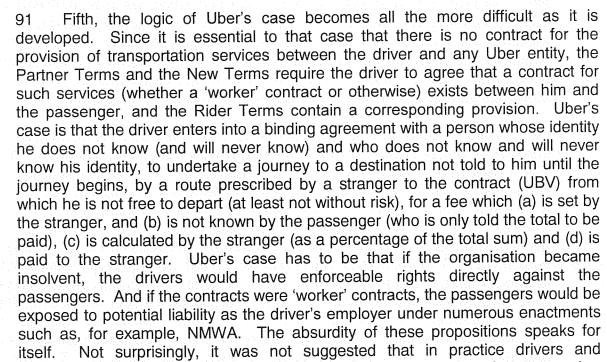

In a dense paragraph (screenshot below) setting out its fifth reason for reaching the conclusion that Uber drivers are working for Uber as drivers, the tribunal articulates the Kafka-esque logic deployed by the company to try to eschew responsibility for being the employer of a very large workforce — concluding that: “The absurdity of these propositions speaks for itself.”

Its full reasoning in reaching its conclusion runs to more than ten points, and the ruling document is 40-pages long — so there’s plenty to keep Uber’s lawyers busy as they figure out their next steps.

The tribunal is asking the various parties involved to submit written representations no later than December 2 to set out how they intend to proceed — urging communication between them and an attempt to achieve “as much common ground as possible”.

Commenting on the ruling in a statement, Guglielmo Meardi, a professor of Industrial Relations at Warwick Business School, said: “The Uber ruling will demystify much rhetoric on the ‘gig economy’ being inherently liberating, and stimulate the debate on the opportunities, limits, challenges and ways of addressing the new forms of contracting work and activities that do not fit into the traditional categories of work.

“As many rights and obligations are based on these categories — from social protection rights (such as working time or minimum wage coverage) and contributions, to taxes and representativeness — it is of paramount importance to clarify how digitalised activities will align with the more established labour market models. While these are redefined, the safer default option may be to consider these forms of work as employment rather than self-employment.”

The ruling document includes details of how Uber pays drivers, with the tribunal noting this is done weekly and that the fee it charges on its standard product is 25 per cent of the fare of a journey. (The fee has risen and stood at 20 per cent when the complainants bringing the case started driving for Uber). And it notes being shown documents “which evidence [Uber’s] disproval of drivers soliciting tips”.

It also flags up as noteworthy the fact that Uber’s Partner Terms require drivers to “support Uber in all communications”, including placing requirements on workers such as refraining from speaking negatively about the company and its business in public.

The document details Uber’s various stipulations on drivers — such as the need to maintain an average 4.4 rating or above or else face “quality interventions” and removal from the platform if their ratings do not improve.

“Over recent years self-employment has increased, but often coming with very bad conditions, prompting fears that it was being used to bypass employment legislation,” adds Meardi.

“With emerging platforms like Uber, nominally self-employed workers are more at risk of exploitation, hence the need for stepping in with more protection, especially in a country like the UK where overall employment and transport regulations are looser and the potential for exploitation, bigger.”

The employment status of the thousands of so-called ‘freelance contractors’ powering the growth of many gig economy businesses has become a increasing bone of contention in multiple markets as tech platforms have rapidly scaled user bases, using technology to tightly manage the people providing the services promised by their apps — mostly without granting these workers employment status.

In London riders providing on-the-ground delivery services for another company in this space, Deliveroo, went on strike this summer — after the company tried to impose new payment terms. The company subsequently backed down in part on the proposed changes.