Every day, we’re starting to hear about startups laying off employees – sizable percentages of them, too. Last week, it was Mixpanel, Maker Media and SOLS.

A recruiter who asked not to be named separately tells us that the grocery delivery company Instacart has parted ways with numerous recruiters in anticipation of a hiring slowdown.

Instacart’s VP of People, Matt Caldwell, confirms that the company is no longer using contract recruiters and is slowing down its total number of full-time hires, but says that’s a reflection of the company’s earlier and aggressive growth plans. He notes that the company grew from 91 full-time employees in January 2015 to 300 full-time employees today.

Either way, not everyone sees major changes ahead. Josh Withers, co-founder of the global startup search firm True, tells us that it’s business as usual as far as he can tell. “Burn rates are being closely scrutinized. We haven’t seen a pull back in terms of hiring, though.” Though Withers half expected to return to work after the holiday to find companies wanting to do more with less, he says that instead, “We came back from break and got a ton of inbounds from private equity firms, VCs looking for help with their startups, and other companies of all stages.”

It could be that companies have “already raised the money and need to put it to work,” he observes. “Maybe [what we’re seeing] lags the macro markets because of the way the money was raised. But it doesn’t feel at all like 2009.”

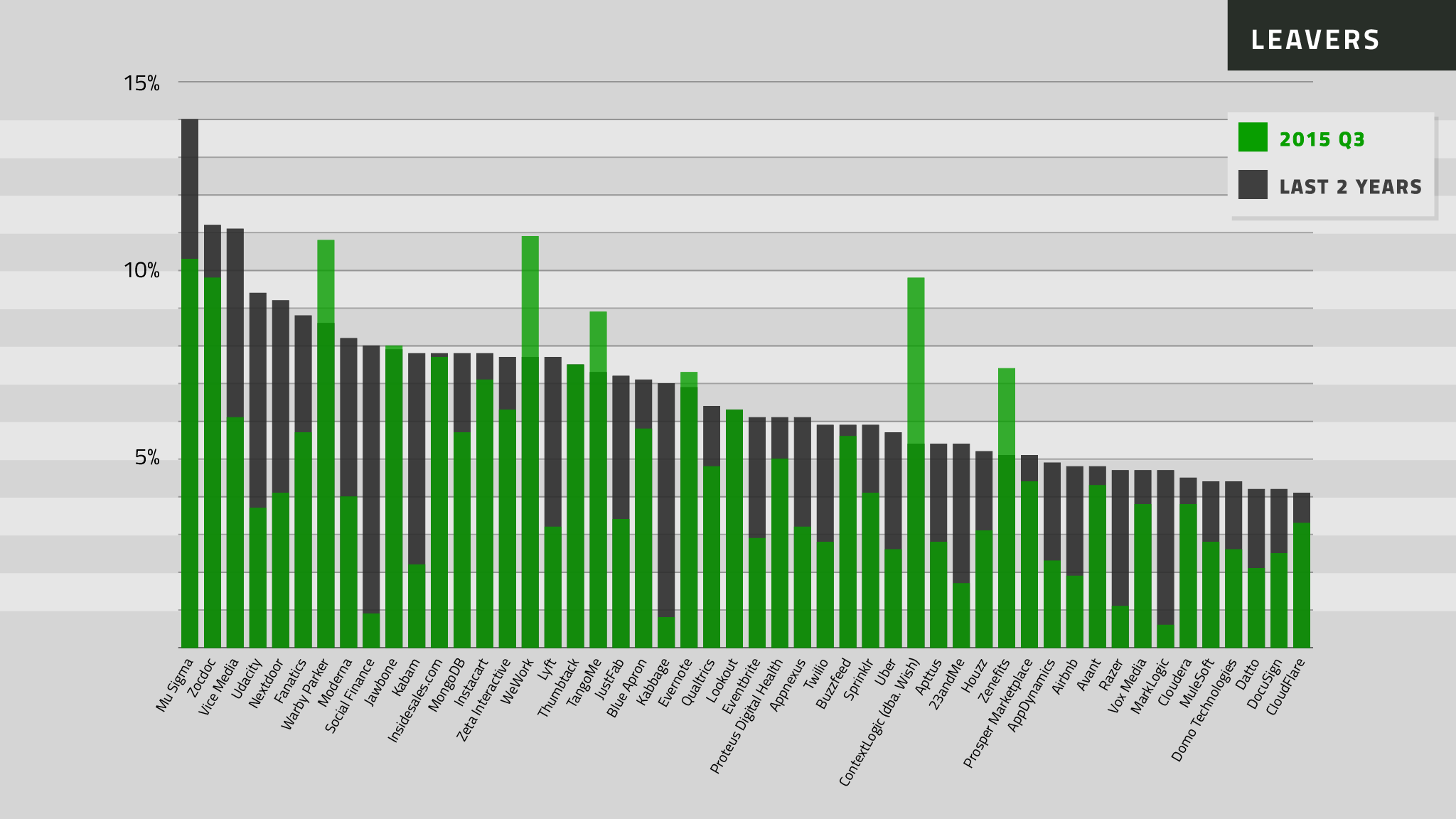

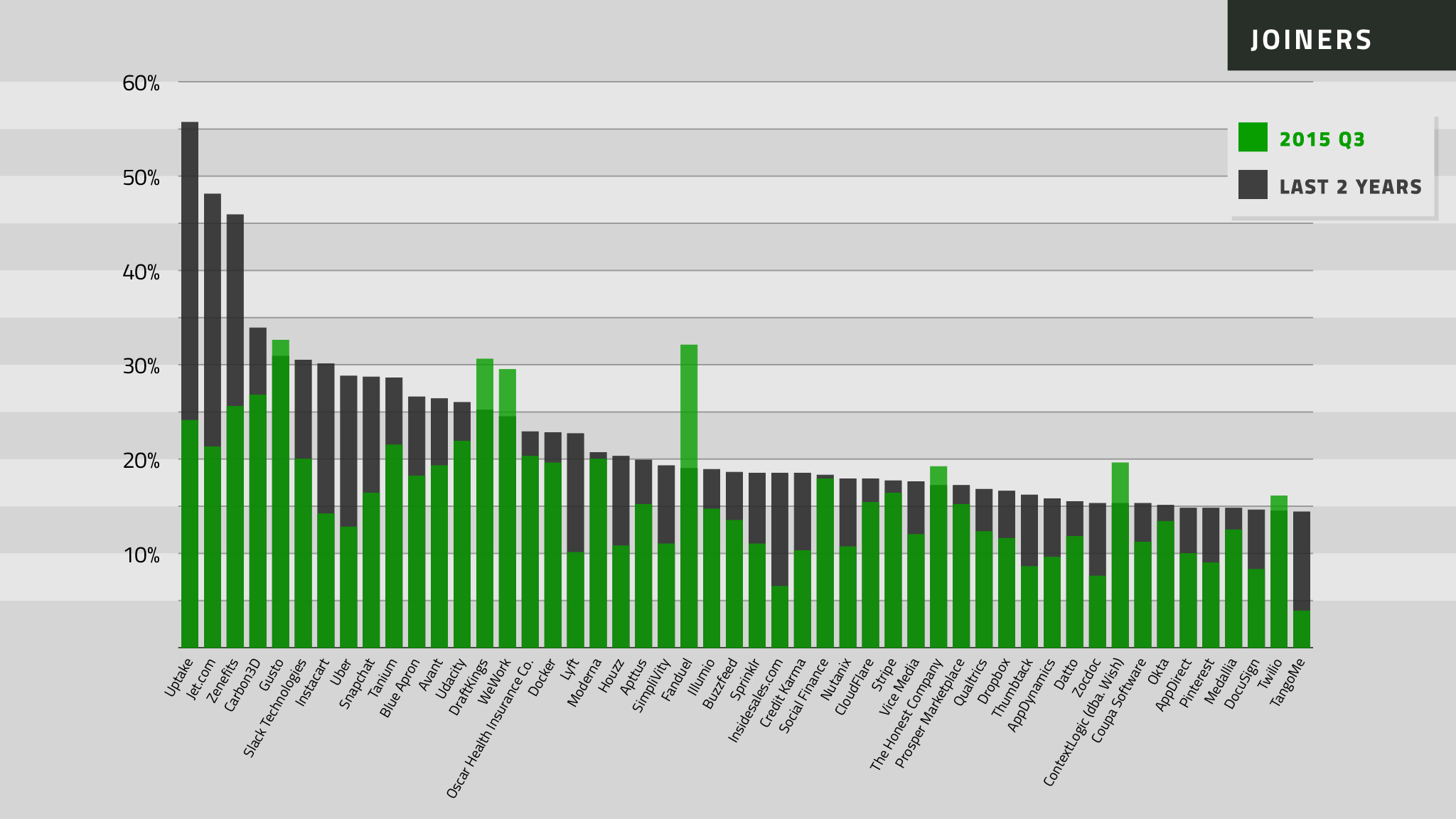

Because it’s so hard right now to know what’s really going on, we worked earlier this week with a set of data scientists with fancy degrees, poring over publicly available data to come up with a list of which U.S.-based, privately held, non-biotech-related “unicorn” companies are hiring the fastest, and which are seeing the most employees leave.

You’ll see that in some cases, the same companies appear on both lists. With Instacart, for example, you’ll see that an average of 7.8 percent of employees left each quarter over the last two years; you’ll also see that the number of new employees grew by roughly 30 percent per quarter, meaning its employees’ net growth was 22 percent. (Caldwell disputes this, saying that number is low.)

We can also tell you that while churn often does say something about the culture of an outfit, our data doesn’t distinguish between people who were laid off and who left voluntarily.

It’s worth noting that while hiring and parting ways with talent can be a leading indicator of broader economic issues – it’s why we decided to create this list — there are plenty of reasons for a company to apply the brakes at various points in its trajectory or for people to switch jobs.

For example, Caldwell says Instacart will likely hire half as many full-time employees per month this year as it did last year, largely because it has already “built ourselves out to be first to market.” Meanwhile, Uber employees whose shares are now fully vested may have moved on to other startups.

As for our methodology: To get to the numbers we did, we simply divided the number of employees at the beginning of quarter with the number of people who left — or joined — that same quarter. We did not include the fourth quarter of last year, because people generally don’t change their profiles immediately after leaving or taking a new a job.