Who saw the recent sale of the Financial Times (FT) from Pearson to Nikkei for $1.3 billion coming? The sale of The Economist, also owned by Pearson, three weeks later, was less of a surprise, as Pearson set forth its new streamlined “digital ambitions.”

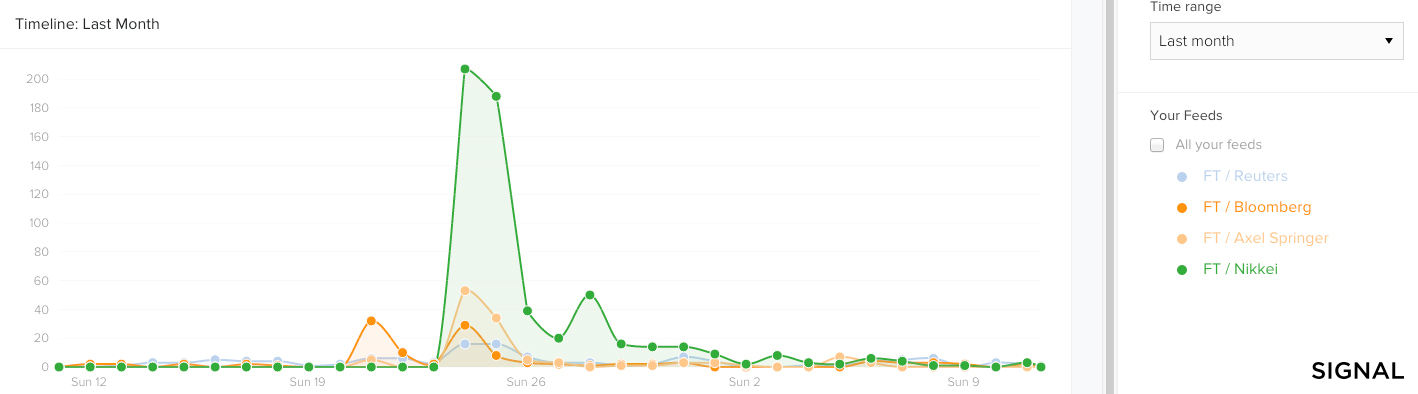

While everyone and their dog was talking about Bloomberg or Axel Springer being the likely new owners (see graph), nobody mentioned Nikkei, despite it being one of the largest media companies in the world. FT journalists even published an article the day before, outlining their publication’s “talks with Springer are further advanced” than with Nikkei (which, by contrast, was only mentioned once in the original FT article).

Now Pearson has sold another big name: the Economist has gone this week for around $731 million (£469m), and Exor will end the week as the largest single shareholder in the Economist Group.

The new owners of both the FT and the Economist have stated their intention to continue pushing hard with new digital initiatives. The Economist, with its daily-digest Espresso app and the FT, with its successful paywall, are already innovative when it comes to their digital offerings, so what could the future bring? I predict that it will involve even more highly personalised digital offerings that give readers the news that they are most interested in up front, as well as increasingly targeted advertising.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) are usually centered around diversification – either geographically or to a different industry – and, of course, they always aim to generate increased profits. The selling company may well have a good reputation, but they’re frequently distressed assets with a falling market value – think Microsoft’s purchase of the ailing Nokia in 2013.

This is why the FT’s acquisition by Nikkei is particularly different to other mergers – especially in media; it’s rare for one successful company to buy another successful, growing one. People usually think of the disastrous AOL-Time Warner merger, rightly recognised as one of the worst M&A deals ever. However, media buyouts have a long history of being risky and ultimately unsuccessful; just look at Vivendi’s acquisition of Seagram in 2000, which saw the merged company lose $15 billion in just one quarter in 2002.

The primary reason why the FT and Nikkei have been such success stories is because both offer unique content you can’t get elsewhere easily stored behind early-adopted paywalls, delivering impressive results in circulation and revenue growth. The paywall meant therefore that people either sign up or stay ignorant. The FT’s digital subscribers have risen 14 percent year on year to “almost 520,000” making up 70 percent of all subscribers, with Pearson citing a “new access model offering paid trials” as a reason for the increase.

Given this very strong digital performance, it’s no surprise Nikkei – which already boasts 363,492 online subscribers – would be interested in buying the 127-year old newspaper. Both outlets have already transitioned extremely successfully to the digital media era, unlike many of their competitors.

At first, the valuation of $1.3 billion may seem inflated, coming in at around 16 times the FT’s earnings (and over treble the valuation of Vox Media); however, this price illustrates that publishing brands with a genuine global cache don’t come up for sale that often. Pearson was in an uncommon position of strength, owning two such brands in the FT and the Economist, and it is no surprise that both have sold for more than commentators initially predicted.

What Nikkei is really banking on in the future with this acquisition is the growth of revenue from the digital audience of the FT, which currently accounts for 70 percent of the total paying audience and which is only likely to rise year on year. The FT is a genuine trendsetter and was one of the leaders of the initial wave of paywall, introducing theirs in 2001, a little after the Wall Street Journal. Other major publishers instead placed their faith in online advertising, which did not deliver the profits expected.

On the flip side of the FT deal, questions will turn to why Pearson would want to sell such a successful commodity. John Ridding, CEO of the FT, suggested Pearson was shifting focus onto “being the world’s best learning company.” However, this year Pearson sold off its only consumer edtech proposition Family Education Network to Sandbox Partners, and also sold off its school software business PowerSchool.

Former Pearson chief executive Marjorie Scardino famously said that the FT would be sold “over my dead body.” It was also Scardino who oversaw the transition from the pink pages of the print edition to, by the paper’s own description, a “multi-channel, digital-first news organisation” – not an unusual statement to hear in the BuzzFeed Age, but one that showed they were at least heading in the right direction.

And the FT really has been winning at digital, especially for the age of the company. Given this situation for Pearson, it seems logical that Nikkei would step in and snap up the FT.

While the buyer of the FT was quite a surprise, the even bigger shock is that we all witnessed something that doesn’t happen very often: two powerful, growing media companies concluding a deal that left each stronger than they were before.

It’s rare for this to happen, and it might actually show other companies that such deals are possible and can come with immense benefits for both parties. Likewise, it will be very interesting to see how the Economist fares following its sale.