First Amendment protections are a solemn oath designed to preserve a functioning democracy; they in no way logically extend to protecting the capacity to inflict harm on vulnerable citizens for mere amusement. For good reason, New York City Councilman Peter Vallone is considering criminal charges against Hurricane Sandy prankster Shashank Tripathi who spread malicious rumors about power outages over Twitter (under the handle, @ComfortablySmug).

While some argue that being a jackass isn’t illegal, since the Constitution’s inception, courts have held that all rights carry the burden of caring for our fellow man. Thomas Jefferson himself said that citizens have “no natural right in opposition to his social duties.”

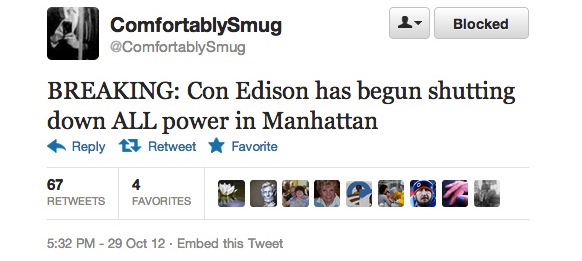

During the height of chaos, Tripathi tweeted widely spread rumors about blackouts.

During a storm, scared citizens act erratically, and could have made life-threatening decisions based on the fact that there would be no power. Tripathi, to his credit, apologized and resigned as Congressional candidate Christopher Wright’s campaign manager. “During a natural disaster that threatened the entire city, I made a series of irresponsible and inaccurate tweets.” Still Vallone worries that without legal punishment, less responsible jackasses with a smartphone will repeat rumors for attention. “I think the consideration of criminal charges will assure this kind of stuff doesn’t happen again,” he told Buzzfeed.

The case against criminal charges was well-argued by TechDirt founder Mike Masnick in the beautifully titled, “Being A Jackass On Twitter Shouldn’t Be Illegal; Public Shame Should Be Enough.” Masnick argues that public shaming has clearly worked, and that legal action would snowball into unnecessary censorship.

Yet, the public shaming case doesn’t acknowledge when there should be limits on free speech. For nearly a century, the Supreme Court has held that citizens who shout “fire!” in a crowded theater are responsible for the deaths caused by the ensuing stampede.

The same holds true for “public hoaxes,” like when in 1938, a negligent reading of H.G Wells’ War of the Worlds, led New Yorkers into mass panic over a fake alien invasion. “Families rushed out of their homes, traffic jams clogged the streets, church services were disrupted, and chaos ensued,” writes lawyer and radio producer, Justin Levine. “Hospitals treated people for shock and hysteria, while police switchboards were so swamped with calls that they could not conduct regular business.”

The Federal Communication Commission again upheld the rule when a radio announcer caused panic after imitating an official warning of a nuclear attack during the first Gulf War.

The case against public shaming is that, during a crisis, Twitter isn’t a magical marketplace of ideas, where citizens are given sufficient time to weigh competing claims and come to a reasonable conclusion. Adrenalin is pumping, there’s not enough time for credible sources to sniff out the truth, and people get hurt.

For those worried about snowballing censorship, constitutional law expert Richard Delgado provides a nice legal bright line, saying that unprotected utterances “invite no discourse, and no speech in response can cure the inflicted harm.” By the time New Yorkers knew the truth, faint counter-whispers against the rumor on Twitter may have been too late to make up for the harm done.

Twitter is a powerful tool of free speech, but thinking that social media is an oasis of truth is a fantasy. We live in a society, and our actions can hurt. It belittles the First Amendment to confuse the solemn obligation of enlightened discourse with the capacity to cause panic for mere amusement.