Something really scary is happening on the internet. It’s a horror story unfolding in front of us, in three simple acts.

Back in 1993, we joked about it: Anyone could hide behind a screen name, but how bad could it get? Maybe we’re about to find out.

AI technology is improving fast enough that I recently had a bit of an existential crisis, wondering if I, too, was an AI. People have no idea what’s real and what isn’t on the internet. With the 2024 presidential election coming up, we have a recipe for disaster.

We may be so comprehensively copulated at this moment in time that digging our way out might prove impossible. Brew a cup of coffee and take a breath; this isn’t going to be pretty.

Media literacy

Now I should be clear that when it comes to media literacy, I’m not worried about new voters; people born in 2005 never knew a pre-internet world. They grew up with screens and a healthy skepticism of the news, and even kindergarteners are being taught media literacy.

But there’s an age gap: 46% of adults say they were never taught how to evaluate news stories for bias and credibility. This lack of media literacy often means that people looking for reviews of things don’t really know what they are looking for, and many fail to spot a disreputable source when they see one.

For a long time, the only place we really ran into this issue was in the context of affiliate marketing. For example, I recently was looking for a two-way radio to take on holiday, and I found a Walkie Talkie Guide, which includes hundreds of “reviews” written either by an AI or some poor copywriter who has never touched any of these products. The reviews are frustrating, unreadable, barely make sense and — most importantly — earn the site money when you click on a link to, say, Amazon.

These click-baity sites have been around for a long time, and the problem has always been language: It’s hard to find a motivated content creator cranking out 5,000 reviews of products based just on the information you can glean from Amazon, only to link back to the source of the information, which is Amazon.

Compare that with Outdoor Gear Lab; the site has a photo of all the radios side by side, and the reviews contain photos of people using the actual devices. The site also seems to regularly update its content, which makes sense: If the content looks fresh, people are more likely to trust it, and they are more likely to click on the link, buy the products and generate affiliate revenue.

It makes sense when you are updating thousands of pages that you occasionally forget to insert the date that you made the change. Image Credits: Screenshot of Outdoor Gear Lab

The thing is, when you know what to look for, and you start looking for that, you find these types of sites everywhere, and it intersects with the piece I wrote a year ago about SEO scammers buying up expired domains: Some folks will throw dozens and dozens of sites up on the web, each containing thousands of articles, customized just enough that Google sends some traffic their way, which then gets clicked on, which then results in someone making a purchase and reaping the affiliate rewards.

But in the scheme of things, and especially this article: Who cares if someone accidentally buys the ninth-best product instead of the second-best? Sure there may be serious environmental impacts to keep in mind (for instance, products that don’t perform well often don’t get returned or repaired: They end up in landfills), but that aside, it’s fine. Things get a lot worse when we get to …

Politics

The media landscape has long been filled with players who have a political bent. The challenge, then, is that news that’s partially true, or straight-up fabricated, saw a huge upswing during the 2020 election and the wild news cycle we’ve seen around COVID-19. “Misinformation is a powerfully destructive force in this era of global communication, when one false idea can spread instantly to many vulnerable ears,” concluded one research paper.

With dubious review sites, you may be able to trick some folks into buying a product or two and make a buck or $8 billion, but at least you’re not changing the future of civilization.

The potential impact of fake news is catastrophic: If people can’t tell the difference between what’s real and what isn’t, and then share that incorrect news with their friends and family on Facebook, you get measurable changes in how people behave. We saw how that led to a whole bunch of attempts to overturn the 2020 election and a House Select Committee report concluding that “many individuals involved in January 6th who were provoked to act by false information about the 2020 election repeatedly reinforced by legacy and social media.”

Woof.

It doesn’t help that foreign government-sponsored hackers have been linked to serious attacks, whether that amounts to stealing money (there was the half-billion Axie heist last year, and many others besides), China-based hackers attacking journalists, and the wave of possibly Russia-sponsored ransomware and hacks targeting U.S. agencies.

That was back in 2020. You know what happened since then? AI. Which brings me to the thing that really scares the bejesus out of me …

Hello, computer

In the years since the most recent U.S. presidential election, we’ve seen extraordinary progress on a few fronts. Generative AI is up there with the most intense avenue of development. Corporates, scared to be left behind, are pouring billions of dollars into research and development, and VCs, not to be left behind with damp check books, leapt into the fray as well.

What happened next was extraordinary: dozens of technology breakthroughs in AI, including language models orders of magnitude more complex than the ones that came before them. AI can create music, fully automated audio ads, and it can make scarily accurate videos of dusty hippies on the playa. Even the best detection methods are useless and can’t reliably figure out what was written by the human finger or by a puffy robot cloud.

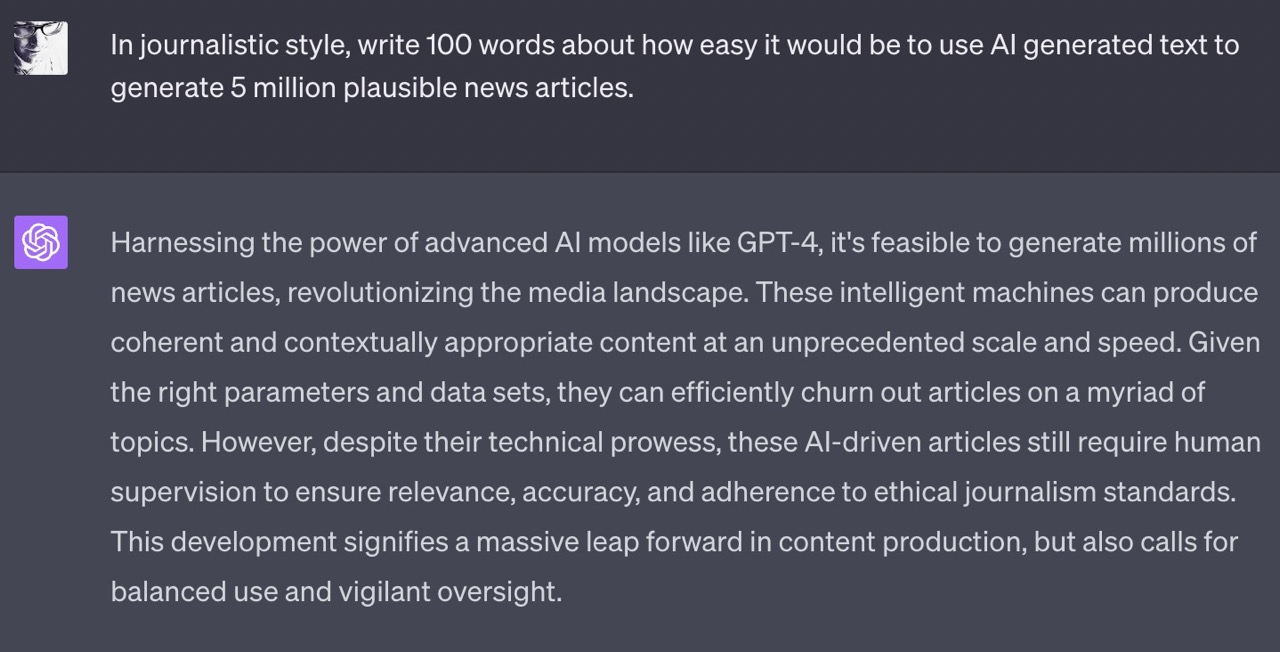

Harnessing the power of advanced AI models like GPT-4, it’s feasible that millions of news articles could be generated, revolutionizing the media landscape. These intelligent machines can produce coherent and contextually appropriate content at an unprecedented scale and speed. Given the right parameters and datasets, they can efficiently churn out articles on countless topics. However, despite their technical prowess, these AI-driven articles still require human supervision to ensure relevance, accuracy and adherence to ethical journalism standards. This development signifies a massive leap forward in content production but also calls for balanced use and vigilant oversight.

How do I know? Because the above paragraph was largely written by GPT-4. I can’t find fault with a single word of it — except if I were really out to deceive, I’d delete the part about ethics. Here’s the original:

Yeah. That’s what I’m worried about, friend. Image Credits: Screenshot from openai.com

We are already seeing a bunch of examples of how this is having real-life consequences. Earlier this week, an AI-generated image of an explosion at the Pentagon sent the financial markets into a brief moment of panic before the truth had a chance to get its boots on.

It’s been a long time since I’ve truly been terrified, but the combination of the three things above, yep, that does it.

A perfect storm

So, what happens when we have a generation of people where almost 40% don’t trust media at all, and 75% can’t tell the difference between false or “real” news in any case, with a presidential election coming up where people are willing to fight dirty, and with AI being able to generate more content than any human can consume?

This really isn’t going to end well. And, in a country where something “not ending well” all too often ends with serious consequences — at least the Jan. 6 attack mob was largely not armed with guns — my fear is that we might not get that lucky next time.

So, what can you do? Start by educating yourself about media literacy — KQED has a great resource — and try to invite others to do the same. If you’re a startup founder, think about how you might be able to apply what you know about technology and AI to combat the almost-infinite deluge of false information we are about to face.