Spending for consumer digital healthcare companies is set to explode in the next few years; the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology is currently reviewing the requirements for data sharing with the Department of Health and Human Services, and their initiatives will unlock a wave of data access never before seen in the U.S. healthcare system.

Already, startups and large technology companies are jockeying for position over how to leverage this access and take advantage of new sensor technologies that provide unprecedented windows into patient health.

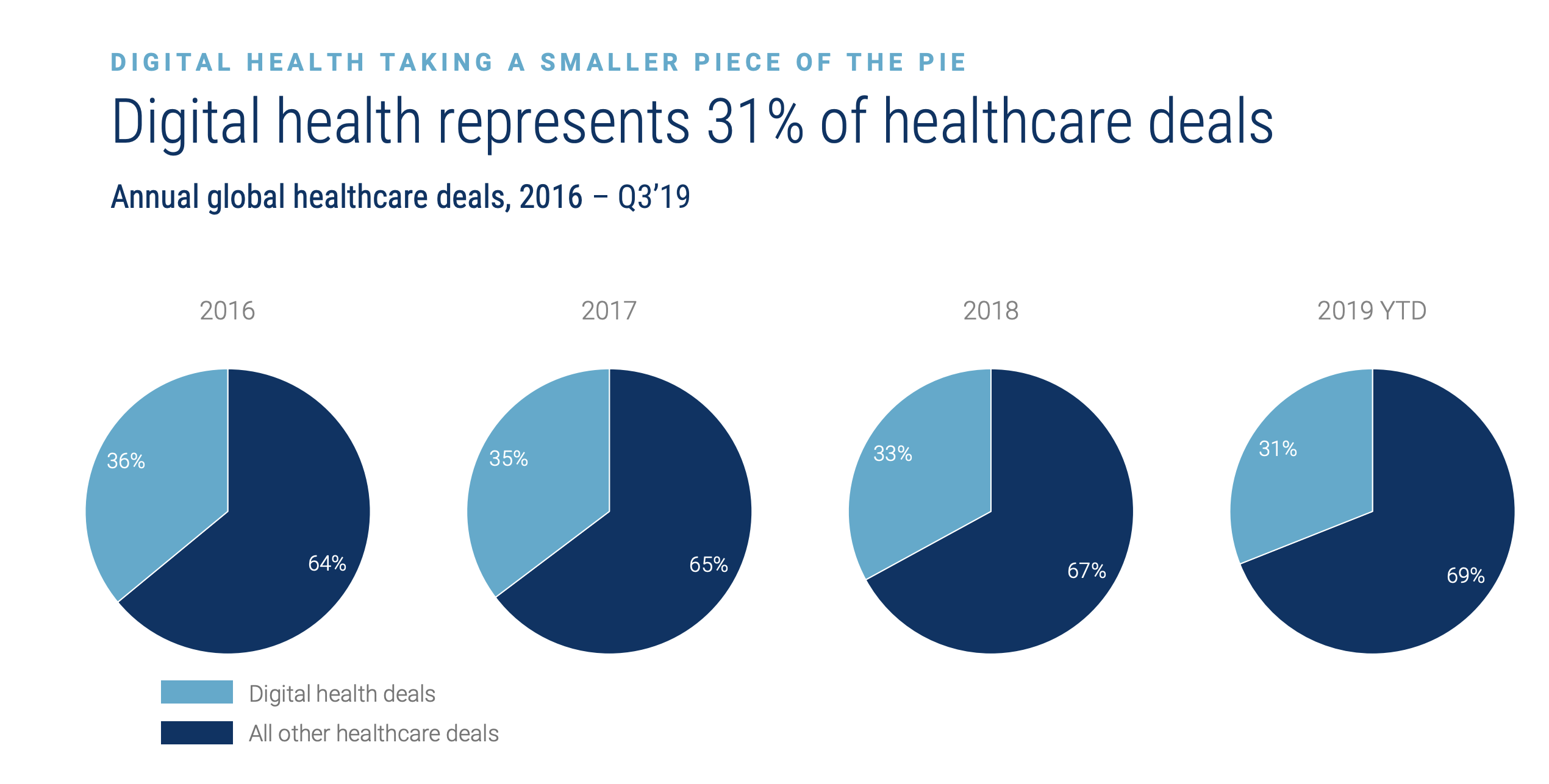

Venture capital investors are expected to invest roughly $50 billion in approximately 4,500 startups in the healthcare industry, according to data from CB Insights. In all, there have been 3,409 investments made in the healthcare market through the third quarter of 2019, with 31% of those deals done in what CB Insights identifies as digital health companies.

The explosion of data is unprecedented and already companies like Apple and Google are jockeying for control over how that data will be served up to healthcare practitioners and patients.

Chart courtesy of CB Insights

Apple and Google are setting out two divergent paths for handling patient data. For patient advocates, there’s a clear winner, and as startups look to play in these emerging ecosystems, it’s what the patient wants that may matter most.

“The second that this data hits those shiny Silicon Valley apps, instead of being under HIPAA that’s covered, you become a user and you have no rights,” says one patient advocate.

Last week, after reports in The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, Google confirmed the details of a partnership with religiously-affiliated hospital and assisted living network, Ascension, a deal that involved the movement of millions of patient records into Google’s infrastructure.

The Alphabet subsidiary had first announced the agreement in its July earnings call, but the precise details of its work with the hospital records of Ascension patients were undisclosed until a more detailed description of the project was leaked by a whistleblower.

Google was not only moving patient records onto its cloud infrastructure, but was also developing tools to “help Ascension’s doctors and nurses more quickly and easily access relevant patient information, in a consolidated view,” the company confirmed in a blog post.

For the source of the Journal’s reporting, there were too many pieces of information about the project that both the Google engineers who were working on “Nightingale” and the doctors and patients in the Ascension healthcare system were kept in the dark about.

As the whistleblower wrote in a Guardian editorial late last week:

With a deal as sensitive as the transfer of the personal data of more than 50 million Americans to Google the oversight should be extensive. Every aspect needed to be pored over to ensure that it complied with federal rules controlling the confidential handling of protected health information under the 1996 HIPAA legislation.

Working with a team of 150 Google employees and 100 or so Ascension staff was eye-opening. But I kept being struck by how little context and information we were operating within.

What AI algorithms were at work in real time as the data was being transferred across from hospital groups to the search giant? What was Google planning to do with the data they were being given access to? No-one seemed to know.

Above all: why was the information being handed over in a form that had not been “de-identified” – the term the industry uses for removing all personal details so that a patient’s medical record could not be directly linked back to them? And why had no patients and doctors been told what was happening?

I was worried too about the security aspect of placing vast amounts of medical data in the digital cloud. Think about the recent hacks on banks or the 2013 data breach suffered by the retail giant Target – now imagine a similar event was inflicted on the healthcare data of millions.

Google insists that no patient data is being used to sell ads, or being coupled with either its own consumer data or data from other customers it may be working with in healthcare (a list that includes the Cleveland Clinic, Hunterdon Healthcare, and McKesson).

However, Google’s handling of patient data — through its own work with other partners and through DeepMind Health (a division of a Google spinout which the search giant recently acquired) — has been controversial.

In 2018, the search giant’s work with the U.K.’s National Health Service was criticized for not adhering to data governance standards and potentially breaking the law. And, earlier this year, Google was sued for allegedly mishandling patient data by including too much potentially identifiable patient information used in a study conducted by the University of Chicago Medical Center, Google, and the University of Chicago.

In each instance, Google insisted that it followed all appropriate regulations, but the problem that the company faces is growing concern from a new crop of lawmakers and concerned consumers that the regulations which exist on the books are no longer appropriate.

Technology is coming for healthcare data

The news of Google’s work with Ascension and the concerns it has raised among consumers is just one example of the company’s broader efforts to capture more of the multi-trillion dollar healthcare market.

Google kicked off November with a $2.1 billion bid for Fitbit — a deal that would potentially put an incredible amount of currently unregulated consumer health data squarely under the magnifying glass of Google’s mammoth data analysis tools.

Coupling that information with health data that hospital systems manage through Google’s cloud tools would give doctors a potentially more holistic view of patient health. Conceivably, one that could be created with or without a patient’s approval, depending on whether Google designs a system that’s opt-in or opt-out for data sharing.

In many ways, Google’s designs for greater access to consumer health information simply mirror what every other technology developer in the healthcare industry is hoping to achieve.

As digital diagnostic tools from toothbrushes to wearable watches have opened a new window into consumer health, technology can potentially encourage patients to pursue preventive healthcare measures rather than seeking care after they’re ill, steps that can drive down costs for everyone.

“All of us… we’re pursuing the same thing,” a prominent healthcare executive at a multinational medical device manufacturer told TechCrunch. “We see a healthcare system that’s highly inefficient with a lot of waste that is very much episode-related, where we all know health is dynamic and continuous.” Gaining “better insight into health and disease drivers and interventions at the right place and the right time is the holy grail.”

Even as consumers (and tech companies) get increased access to digital biomarkers that can present one window into patient health, researchers and drug developers are hoping to access the same tools for clinical trials and studies that can offer valuable information for drug discovery and development.

That’s why Apple launched the Apple Research app to compliment its Apple Health app, earlier this month. Just as Apple has a HealthKit suite of tools for developers looking to use health data from Apple devices to develop new services, the Research app uses Apple’s ResearchKit tools to collect data for clinical health experimentation and data aggregation.

The opt-in studies that Apple is including with the Research app center around women’s health, heart health, and hearing. Through a study with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the research app will be collecting cycle tracking logs to study women’s health; while working with the American Heart Association and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Research will collect data during workouts and heart rate and activity data to try to determine waring signs of atrial fibrillation or heart disease. The final inaugural research study comes from the University of Michigan and the World Health Organization to collect data about sound exposure from the iPhone and Noise app on Apple Watch, along with surveys and hearing tests.

Apple has also recently announced an agreement with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to give VA patients access to their health records through Apple devices and the Apple Health app.

Google’s parent company, Alphabet, has similar research initiatives in place through the work of its healthcare-focused subsidiary, Verily. That South San Francisco-based company has developed a clinical wearable device that’s being used for several research initiatives with healthcare companies.

Meanwhile, Facebook the social media giant whose reputation is probably the most tarnished by a slew of privacy scandals, began taking its own tentative steps into healthcare this Fall.

Using anonymized data from its collection of profiles, Facebook is working with the American Cancer Society, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop a series of digital prompts that will encourage users to get a standard battery of tests that’s important to ensure health for populations of a certain age.

The company’s initial focus is on the top two leading causes of death in the U.S.: heart disease and cancer — along with the flu, which affects millions of Americans each year.

Users who want to access Facebook’s Preventive Health tools can search in the company’s mobile app to find which checkups are recommended by the company’s partner organizations based on the age and gender of a user and where to get them.

The approaches differ in one crucial area — the ability to opt in or out of the services provided. That one feature is a simple first step to putting patients — the object of most healthcare practices — into an agent responsible for their own care.

Where is the patient?

For years, insurers, corporate providers and the government (the payers) and medical providers and pharmaceutical companies (the caregivers) have been urging patients to take more control over their health.

For medical providers consumers represent a source of income that’s potentially unrestricted by the bureaucracy and red tape that’s associated with reimbursement from an insurer. If more patients can decide what they’re willing to pay for over-the-counter, the better.

Meanwhile, payers see better patient engagement and greater personal investment in healthcare as a way to reduce costs for care by engaging in preventive care rather than diagnostic care.

However, the ability for patients to better inform themselves and potentially seek higher quality, lower cost treatment options is dependent on their ability to access their own data and determine how it gets used by the other stakeholders in the healthcare system.

Right now health advocates say that patients are completely unable to take those steps because they don’t control how their health information is distributed and in many cases (outside of Apple’s work with the VA) have little to no easy way to access their medical records.

The desire for transparency and access extends far beyond simply seeing their own records. Patient advocates argue that any developer working on tools to assess or diagnose conditions, or prescribe therapies, open up their methodologies to assessment by healthcare advocates and regulatory agencies.

“Without transparency, it is not possible to know what harms may be for patients affected by ‘black box’ algorithms developed through Project Nightingale,” says Andrea Downing, co-Founder of The Light Collective. “Patients affected by this deal should have a right to be represented when decisions are made by big tech and health systems.”

Downing should know. In 2013, she was a spokesperson for plaintiffs in a Supreme Court case that determined human genes could not be patented, opening the door for broader access to genetic testing for certain conditions.

While that landmark case settled one question over who owned naturally occurring genes, patient data issues abound in nearly every other aspect of digital health and diagnostics.

At the end of last year, Facebook was charged with misusing sensitive health data that was being distributed by private groups. The allegations against the company centered on the push Facebook had made among users to set up private channels where people who were being treated for certain conditions could share information and provide support.

That data, allegedly, was then opened up via Facebook’s application programming interfaces to be used by third parties without the group’s approval.

“What I found that the vulnerability affected all closed groups on Facebook,” said one security researcher who uncovered the alleged abuses. “You could scrape the names and lists of all the real names in these groups and reattach to employer, email, address all without consent.”

As more and more companies enter the digital health space, the critical thing to consider is building a patient-first product, according to consumer advocates like Downing. And the first step is not to do what Google did, says Downing.

“The way I put is no aggregation without representation,” she says. “We want to be part of these deals. We see the need for life-saving data sharing to happen… [but] there’s such little trust right now with big tech, because they’re a business and they want to make money.”