We are heading toward climate disaster, and experts predict that by 2030, the effects will be irreversible. The built environment — building, using and dismantling buildings — have a huge impact on climate change. In fact, the International Energy Agency estimates that real estate is responsible for around 38% of total global carbon dioxide and 36% of total global energy consumption.

TechCrunch+ caught up with Antony Slumbers — the man behind the Trillion Dollar Hashtag — to learn more about what challenges are facing real estate and whether there’s hope. Spoiler alert: There is hope, but we’ll need to act sooner rather than later.

Slumbers told me that there are four major challenges to real estate:

- Decarbonizing it.

- Adapting to the impact of the move to hybrid, distributed and remote working.

- What to do with surplus obsolete buildings.

- Figuring out how to navigate the societal challenge of the three points above.

“This really is not an easy problem to solve,” Slumbers said. But there also might be huge potential here: “When you’re talking about the largest asset class in the world, and a fixed timetable, you have the single largest opportunity space in the world, and huge boom time for prop tech.”

Decarbonizing real estate

The viability of humanity living within planetary boundaries rests on the action we take in the next seven years, according to a recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. There’s a rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a livable and sustainable future for all.

“Climate change will and is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every reach of the globe, and it will lead to an increase in global warming in the near term,” Slumbers said. “And we’re likely to reach 1.5 degrees between 2030 and 2035. To keep within the 1.5-degree limit, emissions need to be reduced by at least 43% by 2030.”

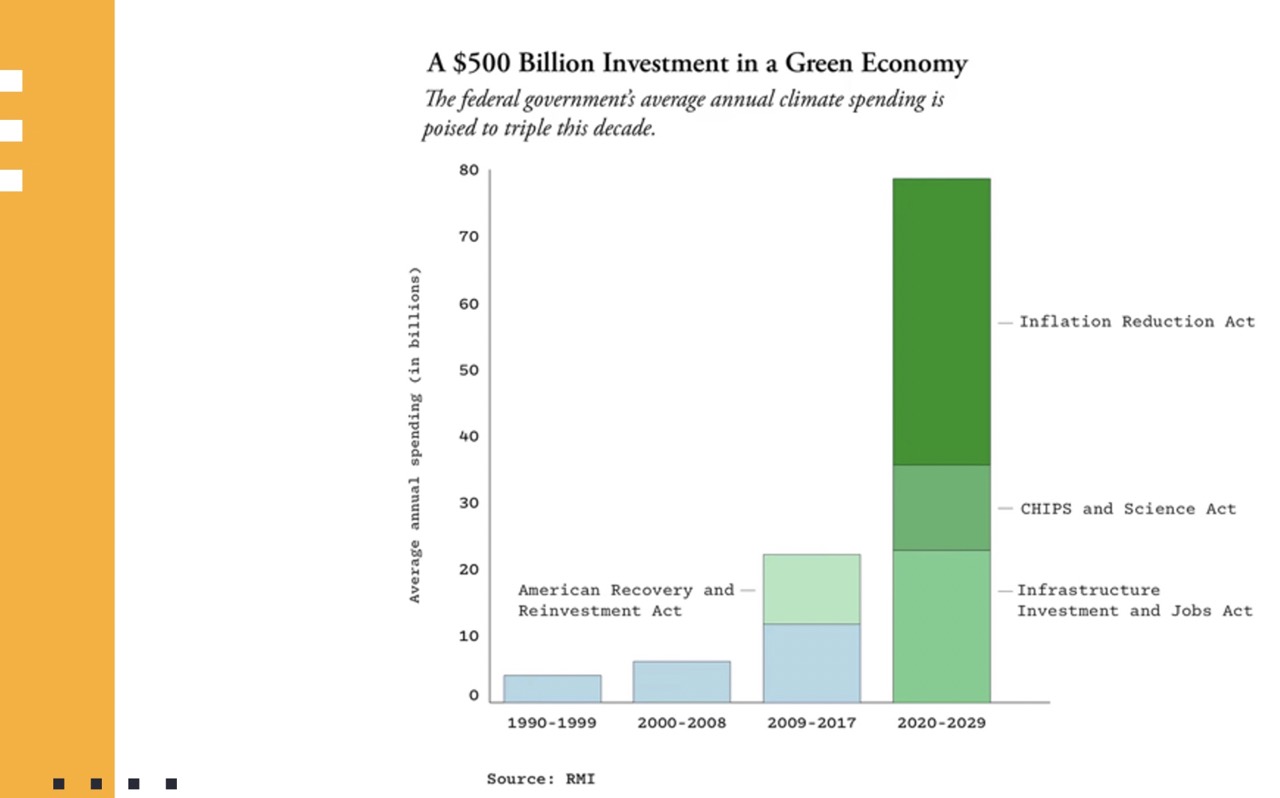

Spending on green buildings and property tech is skyrocketing, opening opportunities for startups in this space. Image Credits: Antony Slumbers

It turns out, we aren’t doing great on this front.

“Following the easing of COVID restrictions in 2021, demand in buildings increased by nearly 4%, and it actually grew by 3% against 2019. We are meant to be halving energy consumption, but we’re not halving anything. We’re going in the wrong direction,” Slumbers said.

In the U.K., the Climate Act is gunning for net zero by 2050, but 85% of the commercial real estate in the U.K. does not meet the standard that the country is meant to hit by 2030. That’s a problem: It won’t be possible to find tenants for a building that isn’t up to snuff, which is going to have huge financial and social repercussions. Buildings that aren’t green are facing a “brown discount”: huge losses of value because they become a lot less desirable.

Shifts in working patterns

Slumbers argues that it was a lot easier to understand what an office was for in 2019: It was a physical space where employees would go to work. It was the primary location of work where employees would interact and collaborate, and a critical component of corporate culture. It included resources, amenities and specialized spaces to do stuff. But there was a dark side.

“Commuting has always sucked. It hasn’t just sucked since after COVID: Everyone has always hated commuting,” he said. “The longer the commute, the more people hate it. We always were really irritated by distractions and interruptions and bloody noise and open plan offices. We didn’t have any privacy.”

When the COVID pandemic hit, there was a sudden and immediate shift away from offices, which brought its own challenges. Post-pandemic, the pendulum swung the other way a bit. Long term, it seems reasonable to assume there will be a hybrid model: Some work is done at home, and other work is done in offices. All of this involves change, however, and you know what humans are bad at, and corporations are even worse at? Change.

“Yes, we didn’t like commuting and all that, but all this working-from-home stuff just seemed a bit too difficult. And then boom! We all got sucked into this black, black hole,” Slumbers said.

The challenge was poorly managed companies, with cultures of closely monitoring employees and managers doing busywork. With everyone suddenly working remotely, it quickly became obvious what worked and what didn’t.

All of this means that the needs of buildings, and what we need from offices and workspaces, is going to continue changing. Employers might love the platonic ideal of an office, but they’re not going to pay a fortune for swanky spaces nobody is using. Even TechCrunch+’s parent company, Yahoo, is getting out of its San Francisco lease. That means that a lot of commercial real estate is suddenly careening toward obsolescence.

“There are two routes for obsolescence. One, you’ve got unsustainable buildings and no economical way of making them sustainable. Alternatively, they’re not fit for purpose; they’re incapable of providing what people want,” Slumbers said.

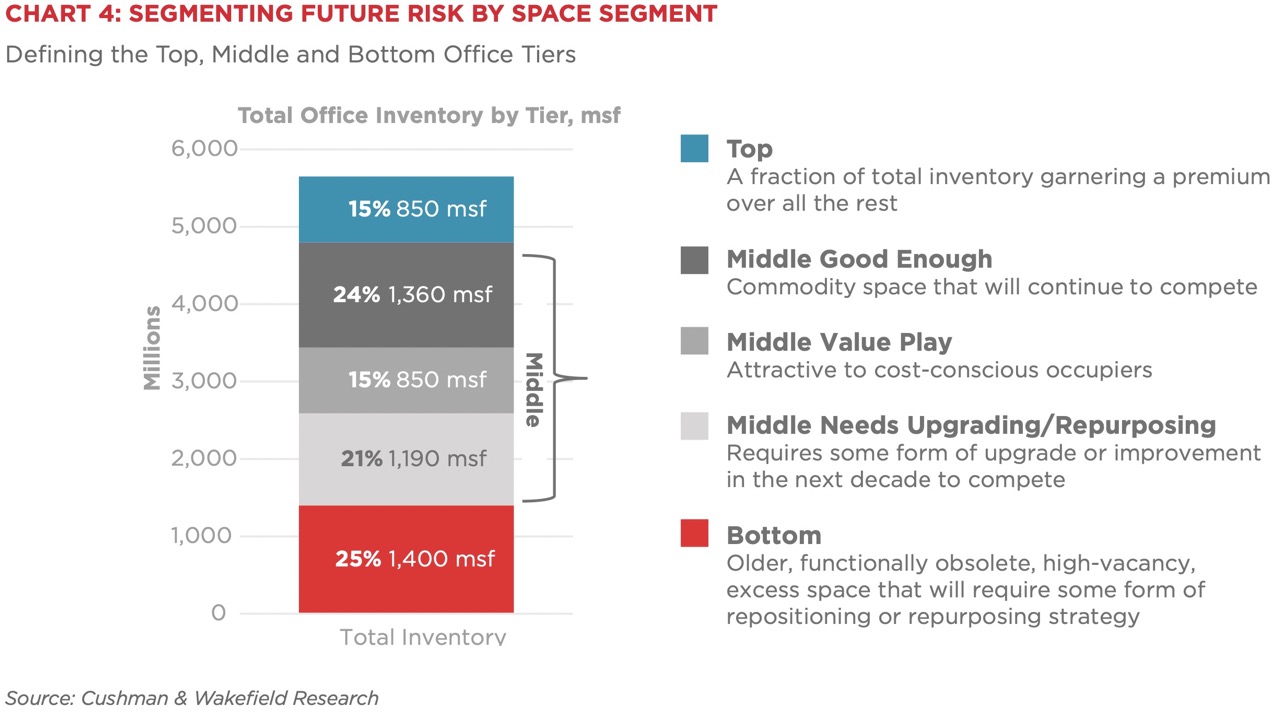

He pointed to a Cushman and Wakefield report in the U.S. and Europe, which concluded supply and demand issues will lead to 330 million square feet of empty office space by the end of the decade. “[That] sounds [like] quite a lot. But actually, they’ve got much, much bigger problems than that because they looked at the whole market, and … only 15% of the entire U.S. office stock was in the top category.”

Almost 60% of U.S. office space isn’t good enough — that’s going to be a problem. Image Credits: Cushman & Wakefield Research Obsolescence Equals Opportunity report

In Europe, 76% of office stock will be at risk of obsolescence. He argues that there are four options for obsolete spaces, roughly breaking down into repositioning the use cases, repurposing the spaces, refurbishing them to be fit for purpose or tearing the buildings down altogether.

“I think mostly, we’re going to refurb and repurpose,” he said. “There are lots of ways we can repurpose space: For office spaces, we could put co-working spaces in there. We could create educational facilities, we could do health care facilities. We can have community or cultural centers. We could have data centers or technology hubs. You could have storage or warehouses. We can do urban farming, or sports or recreational facilities.”

Putting it all together

All of the above represents formidable shifts in what we need from our urban landscapes.

“The bad-news way of looking at it is that these challenges threaten to undermine the economic vitality and social cohesion of cities and may lead to a decline in public services and quality of life for residents,” he said. Without bold actions [and] strategic planning, cities may struggle to adapt to these changes and remain competitive in the rapidly changing global economy.”

But there are other ways to look at it, too. “The creative, visionary, innovator way of looking at it would be to say, ‘Wow, here is an opportunity to create more livable, sustainable and human-centric cities by embracing technology, investing in smart infrastructure and fostering a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship.'”

It would behoove the world of property tech to think of building systems and taking a holistic approach: This could be boom times for the sector, as all eyes are on climate and the built environment.

“We need to prioritize sustainability. We need to promote active transportation. We need to encourage remote work but also incentivize people to come back into city centers. We need to foster inclusion. We need to support affordable housing. We need to foster community, prioritize accessibility.”

Rethinking the way commercial spaces can be used is an extraordinary opportunity for those with an entrepreneurial bent — and now might just be the time to start planting some seeds on that front.