Ever since they were discovered over 100 years ago, superconductors have seemed a bit magical.

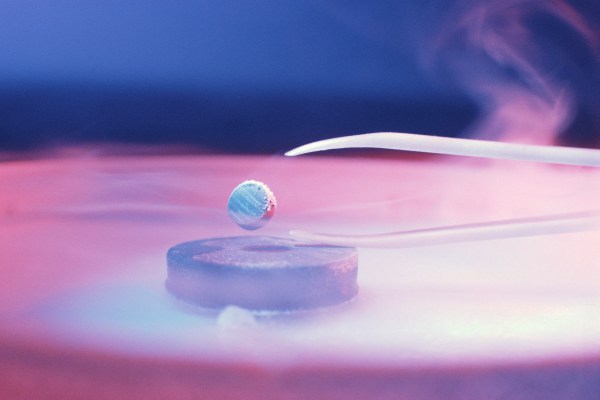

You might have seen one on YouTube, levitating above a pool of liquid nitrogen, shrouded in vapor as the super-chilled seventh element boils off. Or maybe you’ve been inside a much larger one that was cooled by liquid helium, generating tremendous magnetic and radio waves that allowed doctors to peer inside your body as part of an MRI.

Even with their delicate temperature requirements, superconductors have become key players in science, medicine and technology. So you can imagine the excitement when earlier this month, a team of scientists led by Ranga Dias, a professor at the University of Rochester in New York, claimed in a paper that they’d created a room-temperature superconductor, one that exhibits the same magical properties at 69.8 degrees Fahrenheit, to be exact.

If the claims are true, and if scientists are able to refine the product further, it could become a truly transformative technology. Fusion reactors, which rely on superconducting magnets to confine the blazing hot plasma, would grow smaller and cheaper. The electrical grid would stand to be transformed, as lossless superconductors would make transcontinental power lines a reality. Maglev trains might stop being the butt of jokes and become a real alternative to air travel.

In order to capitalize on their research, Dias and Ashkan Salamat, co-author on the paper, founded a company called Unearthly Materials.

I recently stumbled upon a YouTube recording of a virtual talk Dias gave to a Sri Lankan scientific society and university in which he claimed to have raised a $1 million seed round and a $20 million Series A for Unearthly Materials.

In his presentation, Dias claimed to have prominent investors, too. The $1 million seed round featured Union Square Ventures’ Albert Wenger, Spotify’s Daniel Ek, Dolby chairman Peter Gotcher and Wise co-founder Taavet Hinrikus. The Series A included Breakthrough Energy Ventures and Open AI’s Sam Altman; Ek and Hinrikus followed up.

Though its website is spare, and LinkedIn lists just six employees, Unearthly Materials is not exactly a secret. But at the same time, the company isn’t tracked on PitchBook and doesn’t appear on Crunchbase. It’s unusual for a widely publicized startup to raise $20 million without writing a blog post or issuing a press release.

Holy grail of materials science

“Superconductor” is one of those rare scientific terms in which the definition is plainly obvious. It’s called that because it’s truly a super conductor: Electricity flows through without any resistance. When that happens, superconductors also expel powerful magnetic fields.

Those two qualities are why superconductors are incredibly useful, but the low temperatures they require have made them unwieldy and expensive to use. Room-temperature superconductors would flip the script, ushering in a range of new use cases. They’re a sort of holy grail for materials scientists and electrical engineers.

The material Dias and Salamat describe in their new research paper works at room temperature, albeit with an important caveat. To superconduct at room temp, the material needed to be squeezed between two diamonds at a pressure of 145,000 psi. That’s a lot less than previous candidates, which required 100 times as much pressure, but it’s still about 10 times more than the deepest part of the ocean.

When Dias and Salamat submitted their new paper to Nature, the journal put it through a rigorous peer-review process, where researchers selected by the journal poke and prod the results until they’re satisfied. Dias told TechCrunch+ that he and his co-authors shared the recipe for the new material, presumably with Nature and its peer reviewers. “We have had independent observers present for our experiments, and multiple colleagues in the field have reviewed our work and rejected doubts and criticisms on the record,” Dias told TechCrunch+ in an email.

Those doubts and criticisms aren’t unfounded. This isn’t the first time Dias and Salamat have claimed to develop a groundbreaking superconductor. In 2020, they published a paper about a different room-temp superconductor. It also made it into Nature and underwent peer review. When it was published, it made a splash. Dias was named to a Time 100 list alongside Rishi Sunak, Alex Stamos and Amanda Gorman. Some even suggested he might win a Nobel Prize for the work.

But no one was able to reproduce the results, and researchers not involved in the original research or the peer-review process raised enough concerns about the data’s integrity that Nature retracted it over Dias and Salamat’s objections.

Because Dias and Salamat’s claims in their most recent paper echo their retracted 2020 work, still more scientists have begun scrutinizing the pair’s previous work.

In remarkably short order, red flags started popping up. Less than a day after the new paper was published, one of their previous collaborators found data in a 2009 paper that was “remarkably similar” to data Dias published in his thesis; the collaborator has asked the journal to retract that paper, too. Another stumbled across some lines that looked very similar to ones he had written in 2007 for his doctoral thesis. Sensing something was off, he compared Dias’ 2013 thesis against his own using a plagiarism checker. An investigation by Physics Magazine compared the two documents, finding “dozens of paragraphs that match word for word and two figures that have striking similarities.” Dias has apologized and is reportedly working to amend his thesis.

Given the controversy around the 2020 paper, many scientists will remain skeptical about the most recent results until they’ve had a crack at repeating the experiment themselves. But without access to the new material or highly detailed instructions for how to make it, they won’t be able to truly vet the new claims. It’s unlikely that other academic labs have received the recipe in sufficient detail to fully replicate the results, either, based on Dias’ statements to other outlets, including The New York Times and Quanta. Dias said that intellectual property concerns are preventing him from doing so.

Without other labs verifying the claims, it’ll be harder for investors to vet Unearthly Materials.

Who’s who list of investors

“We are growing this company with the very much focus [sic] on how we can bring the material to ambient conditions, [to] develop this technology,” Dias told his virtual audience on March 31, 2021. “We recently raised $20 million just to focus on the science part of this. These are the investors that we use for this kind of technology.”

Dias was speaking alongside a slide with three columns, one for Unearthly Materials’ seed round, one for Series A and one for Series B. The seed and Series A columns were populated with investors including Ek, Wenger, Altman and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. The final column was blank, implying that a $250 million Series B was up next.

When I began reporting this article, I started by emailing a couple of the listed investors. Based on Dias’ presentation, Unearthly Materials would have closed the deals with investors in 2020 or early 2021, yet I hadn’t found any details about the rounds. When someone raises $20 million, they usually tell the whole world about it. I wanted to make sure those figures were legit.

Furthermore, Dias and Salamat’s 2020 Nature paper had been retracted in September 2022, so I was curious about how investors were reacting to the new paper’s claims. Did they have access to the raw data? If not, how would they vet the material? Would the retraction factor into any decisions to participate in a Series B? But my first questions to them were more pro forma: Could they confirm their investment and the size of the round?

The answers were surprisingly mixed. Breakthrough Energy Ventures, Bill Gates’ climate tech fund, said it had not invested in Unearthly Materials and asked me to let them know if I found any other claims of investment. Albert Wenger, who is managing partner at Union Square Ventures and was listed as a seed-stage investor, confirmed that he had made a personal investment in the company, not one on behalf of USV.

Peter Gotcher, who was also listed at the seed stage, confirmed that he, too, had invested in Unearthly Materials. Sam Altman, Taavet Hinrikus and Errol Damelin have not responded to inquiries.

When I reached out to Dias asking him to clarify, he told me via email that investors in his presentation were merely “prospective investors.” “We regret this and have spoken to those involved,” he said.

“Those involved” do not appear to include Daniel Ek, whose name appeared as an investor in both the seed and Series A rounds. A source close to Ek told me that neither Ek nor anyone from Prima Materia, his investment firm, ever met or even considered an investment in Unearthly Materials.

So what happened to the $20 million round? “We ended up closing the round with slightly less,” Dias said. Exactly how much less he didn’t say. The company has yet to file a Form D with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and the only records I’ve found appear to cover the $1 million seed round. How much did those documents say Unearthly Materials raised? $160,000.

It’s possible that the startup has raised more than that, but it’s unlikely to be anywhere close to the $20 million Dias claimed. Unearthly Materials fundraised off the original paper, which is now retracted. The new paper has presumably undergone more pre-publication scrutiny, giving the company fresh ammunition. But enough scientists remain skeptical that investors probably should be, too.