Throw half a dozen entrepreneurs in a room together with a whiteboard, and they’ll be able to come up with a thousand business ideas in a couple of hours. It’s the nature of entrepreneurship. Our brains are wired to keep an eye on what could be better and how that gap in the market can be turned into an opportunity. In other words: Ideas are cheap, and nothing is so awesome that it couldn’t possibly be improved. However, not all problems are worth solving.

There are two common problems with the problem slide. Some founders are tempted to go way into the weeds on this slide, explaining the competitive landscape, market size, customer segments, value propositions and more. I understand the temptation — the problem formulation does touch a large number of aspects of the business — but this is neither the time nor the place.

The other common issue I see in pitch decks is the absence of a problem slide. This happens particularly often with founders who believe that their solution and product slides are so good that the problem itself is obvious and a slide talking about it is redundant. That is a mistake. Even if the problem is universally understood, it’s helpful to see how a founder frames the problem. There are some elegant ways of doing that. Let’s talk about them.

What is the problem?

Being able to clearly outline the problem is a crucial first step toward explaining why people might want a solution. Explaining succinctly and clearly what the problem is can be surprisingly hard for some companies, while others have a much easier path toward a problem statement.

A few examples:

- Internet connectivity is poor in many parts of the world. (Solution: Iridium’s satellite hotspot.)

- Satellites, once launched into space, are either stuck in their predefined orbits or need to bring complex propulsion systems and fuel with them. (Solution: Atomos space tug boats.)

- Training staff is hard and expensive to do consistently. (Solution: Gemba’s VR training platform.)

- Dry cleaning is inconvenient and slow. (Solution: Presso’s at-home dry-cleaning robot.)

- Smoothies and protein shakes separate after 20 minutes, so having them at the gym is hard. (Solution: BlenderCap.)

Now, we can argue about what the market size, customer segment and sensibility of each of these problems are, but all of the above are real problems that companies are working to solve.

Who has this problem?

However you choose to frame the problem statement, the issue you are addressing is being experienced by someone, and it helps to explain to your investors how you are thinking about your user base.

Heads up: Don’t go too far into the weeds here; if you need to break down several different customer segments, that might be what a user persona or a customer archetype slide is for. If you feel the desire to hold up the lens of marketing, then your go-to-market slide is the right place for that. In broad strokes, however, you’ll want to give your investors an overview of what you’re doing here.

You can tell this story by using a single example: “Linda often works on the road but can’t always get reliable internet.” Or by hinting at the market size: “20% of all work-from-home workers lose productivity due to unreliable internet.” What direction you choose depends on how you tell your overall story; some narratives work better with a single example that follows the story of the startup you’re raising money for from slide to slide.

How are they currently solving this problem?

It’s pretty rare that a startup comes across a real problem that people aren’t currently solving in any way. In fact, whenever I’m presented with “people aren’t currently solving this because there is no solution” in a pitch deck, that’s an enormous red flag. If people aren’t experiencing enough pain to solve the problem, why would they start solving it now?

For the smart mug Ember, for example, the problem might be “my coffee goes cold when I’m working.” There’s an existing solution: Make new coffee or put your cup in the microwave for a few minutes. The former takes a few minutes and is wasteful with your coffee. The latter takes a minute but may ruin your flow of work.

Here, we can argue whether anyone truly needs an electric coffee mug (I have one, I use it every day and I love it, but I’m a particularly gear-forward nerdy weirdo), but the point is: Ember can clearly point to a problem that many people are experiencing and have existing solutions for. The question becomes “Is Ember’s solution sufficiently better than the existing solution that people are willing to pay $130 to not have to stumble over to the microwave every couple of hours?” That’s a market sizing and go-to-market question; don’t waste your time with that on this slide — that’s a different part of your narrative.

What are they willing to sacrifice for their current solution?

Assuming you found customers who have a current solution to a problem, you can discover what they are currently willing to sacrifice to “solve” their problem. Some problems are solved with money. Others are solved with time. Others again are solved with inconvenience or suffering the pain without solving the problem.

Imagine having to send a letter. The solution to writing an address on the envelope is simple: You use a pen.

Now imagine having to send 30 letters. You could use a pen, but now you might want to load your envelopes into a printer instead and use a mail merge software package to print each of the envelopes.

Now imagine having to send a hundred letters. Perhaps a label printer starts to make more sense because envelopes jam in home printers frustratingly often.

Ten thousand letters? Forget about it — it’s time to start outsourcing and using a direct mail provider. That is a huge financial outlay, but letting machines take care of the printing and shipping makes more sense than stuffing envelopes by hand.

The opportunity for a startup is solving a problem in a way that is — in one dimension or another — better than the existing solutions. That doesn’t necessarily have to mean that it has to be cheaper or even faster or smaller or more convenient than the existing solutions, but it has to be more “right” for the target audience than their current options.

What’s wrong with the way they are currently solving this problem?

User research is an essential part of your customer discovery journey. Talking to a lot of different customers about how they solve particular problems is helpful.

Imagine the “problem” you are solving is that offices look sad and lifeless. The solution you’ve come up with is an elegant way of hydroponically growing plants in a way that looks beautiful and needs very little maintenance. To figure out if that even makes sense, you need to learn a lot about how offices currently deal with plants.

Some offices have an office manager who buys plants and sometimes waters them. That only works if they remember to water the plants and know enough about plants to choose the right ones based on the temperature and lighting in the office building. Some offices are effectively “renting” the plants, and the service contract comes with someone who looks after them. Other offices may have landscapers on staff. Some might decide to order posters with photos of plants or use silk or plastic plants.

All of these solutions have their own pros and cons; price, convenience, longevity, sustainability, etc. Be aware of all of them, and perhaps highlight the one that is most relevant to your value proposition. Careful, though, again: Your full competitive breakdown goes on the competition slide. Your full differentiated market segmentation goes on the go-to-market slide. And if you have a distinct value proposition, well, you can break that off onto a separate slide, too.

Got some good examples?

As part of our Pitch Deck Teardown series, we’ve seen some incredible problem slides. Here are a few examples:

Forethought

Problem slide from Forethought’s Series C deck. See Forethought’s full pitch deck teardown here. Image Credits: Forethought

The problem of bad customer service costs a lot of money. There’s no argument that that’s a huge problem. Forethought elegantly hints at its market sizing here, along with the problem (and a little about its value proposition).

Alto Pharmacy

Alto Pharmacy’s problem slide is hard hitting and data driven. See the full pitch deck teardown. Image Credits: Alto Pharmacy

Alto Pharmacy leans into inefficiency and waste as the biggest problems in its market, with 90% of scripts being picked up in retail pharmacies, 33% of scripts never getting collected and a -5 NPS score for the largest pharmacy meaning that, well, there’s a lot of room for disruption there.

Dutch

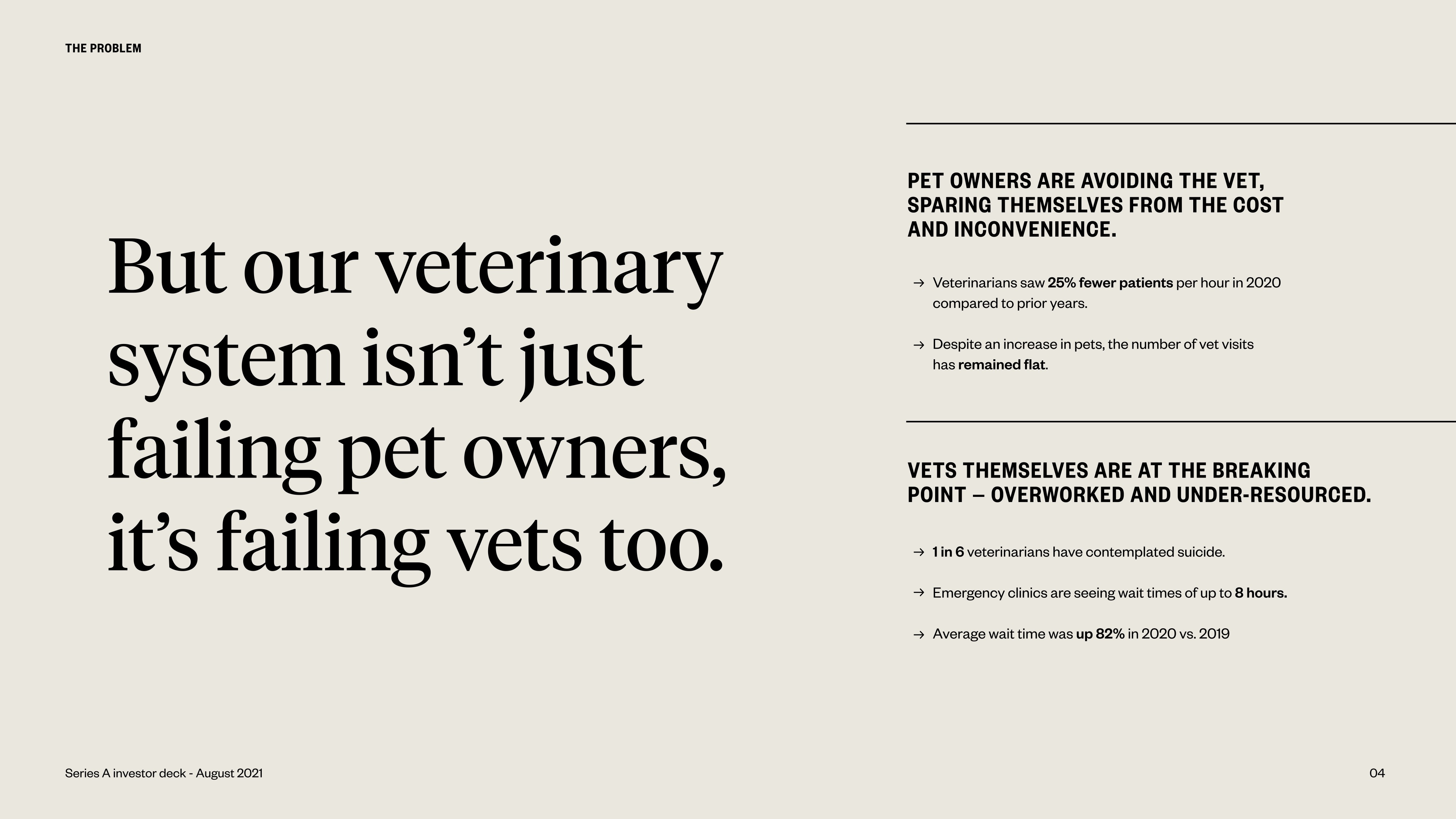

Dutch’s problem slide takes an elegant tack. See the company’s full pitch deck teardown. Image Credits: Dutch

Dutch takes a different approach, highlighting the high cost and low convenience of going to the vet. It also defines its audience (“pet owners”) and a value proposition for veterinarians.

Think company-sized, not product-sized

In the context of fundraising, remember that a feature is not a product. You may create a tool to help people write canned responses for their emails. “Tom sends 900 emails per day, and he finds that he is often saying the same things again and again. He is copying and pasting snippets of text from a Word document he created, but that’s not efficient.”

On the face of it, that’s a real problem worth solving. But is Tom willing to pay for it? Creating it as a standalone company might make sense. Still, it is hard to imagine it being a billion-dollar company. If you get successful enough, other companies will launch templating systems for an email in their core offering. At that point, your business will become irrelevant overnight. To wit, Gmail has templates built-in, and most customer relationship management (CRM) software has snippets and templates built-in, too.

Use great examples!

When telling the story of the problem, it’s helpful to have some examples of how people are currently solving the problem: “Company X had to hire four full-time staff and buy $50,000 of telecoms equipment to set up their SMS infrastructure” is a great way to bring Twilio to life.

“For your web shop, the running of server hardware is painful and unpredictable. If you have a sudden spike in traffic, it can take weeks to get extra capacity, and you might lose millions of dollars as the web pages are unavailable,” is a compelling argument for Amazon Web Services (AWS).

“Linda needs to hire an assistant to deal with her workload” is an excellent argument for automatic account reconciliation and reminder-sending software solutions.

Your job as the founder is to draw a solid, realistic picture of the problem you’re about to solve, explain the pressing need people have for addressing the issue and give an indication of how prevalent the problem is. Don’t forget to include the risks or costs of what happens if the question remains unsolved. If your “problem slide” ticks all of those boxes, you’re on the right path.