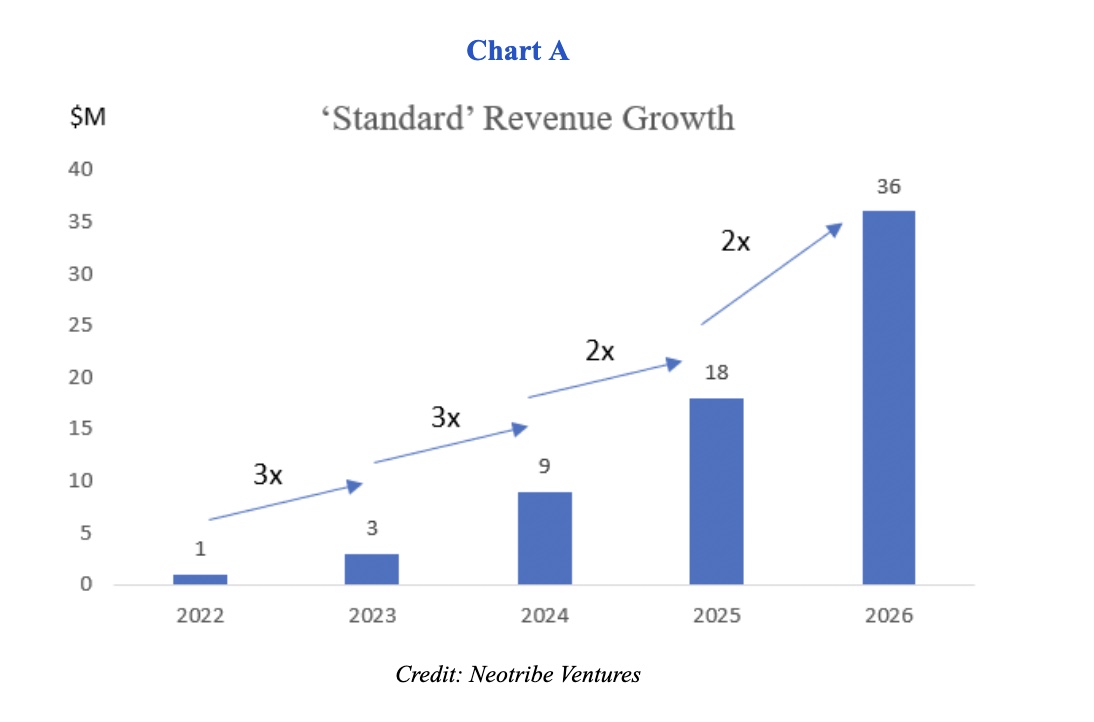

Over the last several years, VC money has been abundant and relatively cheap. This created an environment where everyone’s motto became, “growth at all costs.” Seemingly, the recipe for a successful venture-backed company became very cookie-cutter: Raise capital every 18 months; invest heavily in go-to-market; grow revenue at a “standard” rate that triples in year one, triples again in year two, and then doubles thereafter.

These “VCisms” borne out of an era of plenty have permeated boardrooms and investor meetings everywhere. In fact, the question, “How long do you expect the capital raised to last you?” essentially became a test of intelligence. The only right answer was 18 to 24 months, without any consideration of the specific circumstances of the company.

People may not be saying it aloud yet, but these VCisms are starting to feel outdated. Growth at all costs doesn’t work when capital isn’t readily available or when it is very expensive from a dilution perspective. And, raising capital every 18 months feels very onerous when it no longer takes one month to raise a round and instead takes three to six months or longer.

Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

It’s time to ask ourselves if these VCisms are still relevant or if it’s time to change. First, let’s take a look back.

How did we get to a “growth at all costs” mentality?

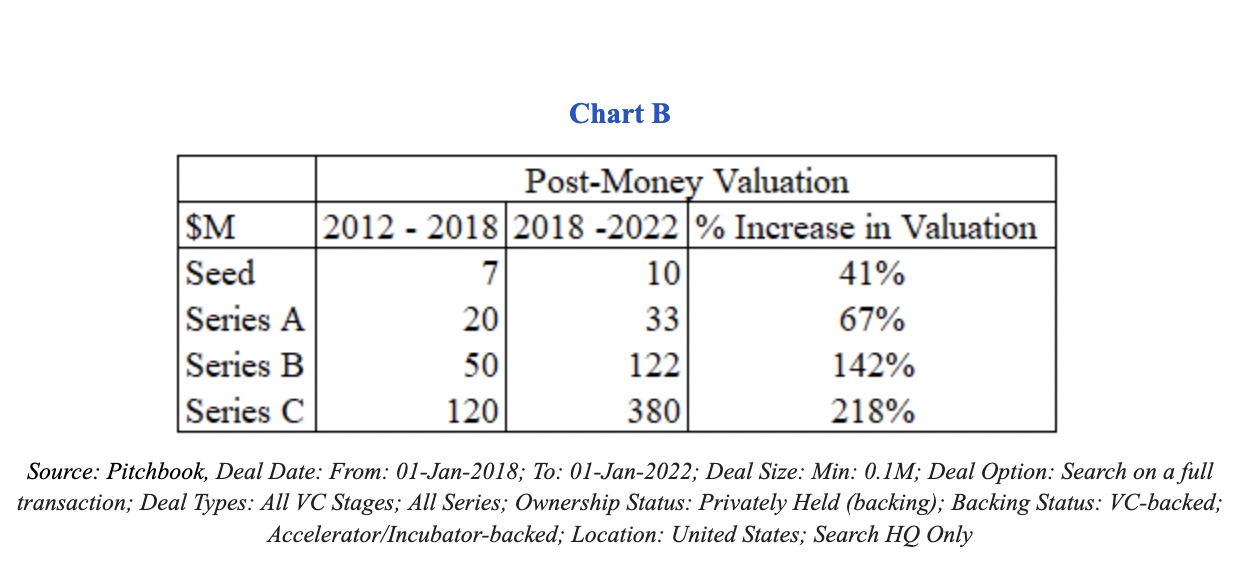

At this point, it’s common knowledge that the cost of capital has declined in recent years. This is mostly discussed by referring to the increased valuations companies were receiving at varying stages, as shown below in Chart B.

Source: PitchBook data from 2012-2022. Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

The sooner we start having company-specific conversations and acknowledge that the cookie-cutter recipe for success isn’t sufficient, the better for all parties involved.

Across all stages, companies were seeing higher post-money valuations, anywhere from about 40% at the earliest stages to over 200% in the growth stages in the 2018 to 2022 period, compared to 2012 to 2018.

Put another way, over the last three years, a company could raise the same amount of capital for less dilution.

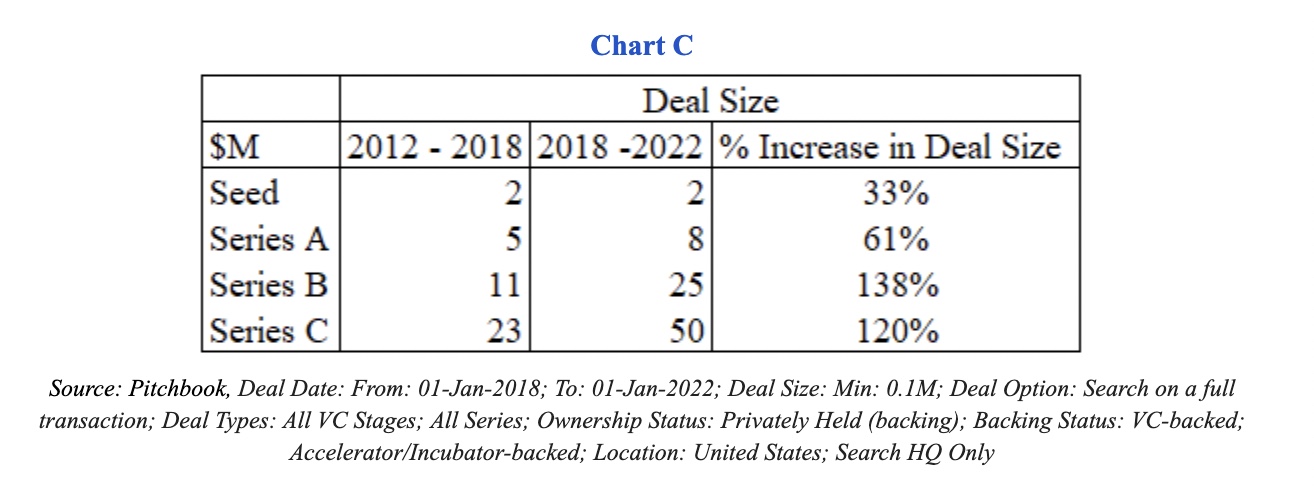

But what isn’t talked about often is the fact that the data shows us that companies did not, in fact, raise the same amount of capital. They raised more capital at each stage — significantly more. As Chart C shows, the median Series C more than doubled in size over the last several years compared to the 2012 to 2018 time frame.

Source: PitchBook data from 2012-2022. Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

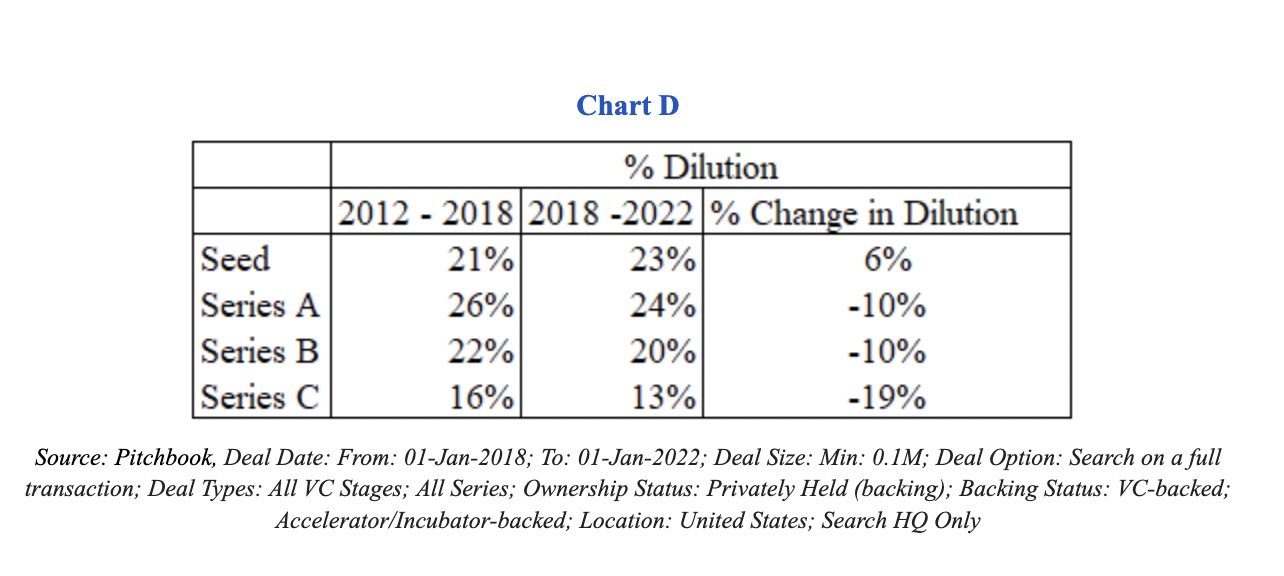

On average, companies saw slightly less dilution, as shown in Chart D below.

Source: PitchBook data from 2012-2022. Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

For example, existing equity holders (seed and Series A investors and founders) saw dilution of a median 22% during subsequent Series B rounds between 2012 and 2018, while their equity was diluted by only about 20% between 2018 and 2022. That’s only a 10% difference.

Notably, companies received more than twice the capital for this dilution (i.e., $25 million versus $11 million, as noted in Chart C) in the past three years. This capital could be used to fuel growth with marketing and by hiring salespeople.

If investors saw similar levels of dilution, does that mean that they saw similar returns?

Definitely not.

Let’s compare the two time periods. Between 2012 and 2018, the median valuation of a Series C company was $120 million. Assuming an investor received 15% ownership in a seed round for around a $1 million check, and then saw their stake being diluted in each round thereafter, the data indicates that their ownership after the Series C raise would be about 7.2%.

Therefore, the investor’s return, on paper, would be: 7.2% x $120 million = $8.6 million. The multiple of the return would be about eight times given the initial check size.

Now let’s compare this to the 2018 to 2022 time frame, when the median valuation of a Series C company was $380 million. Again, assuming an investor received 15% ownership in the seed round (this time with a check of about $1.3 million based on the data) and subsequently saw their stake getting diluted, their ownership after the Series C round would be about 7.9%.

Therefore, the investor’s return, on paper, would be: 7.9% x $380 million = $30.2 million. The multiple in this scenario given the initial check size is about 23 times — nearly triple the return investors saw between 2012 and 2018!

To be clear, founders and company employees benefited from this enhanced valuation environment, too, which is why the cycle of raising large rounds of capital frequently began to become the norm.

Does “growth at all costs work” when costs are rising?

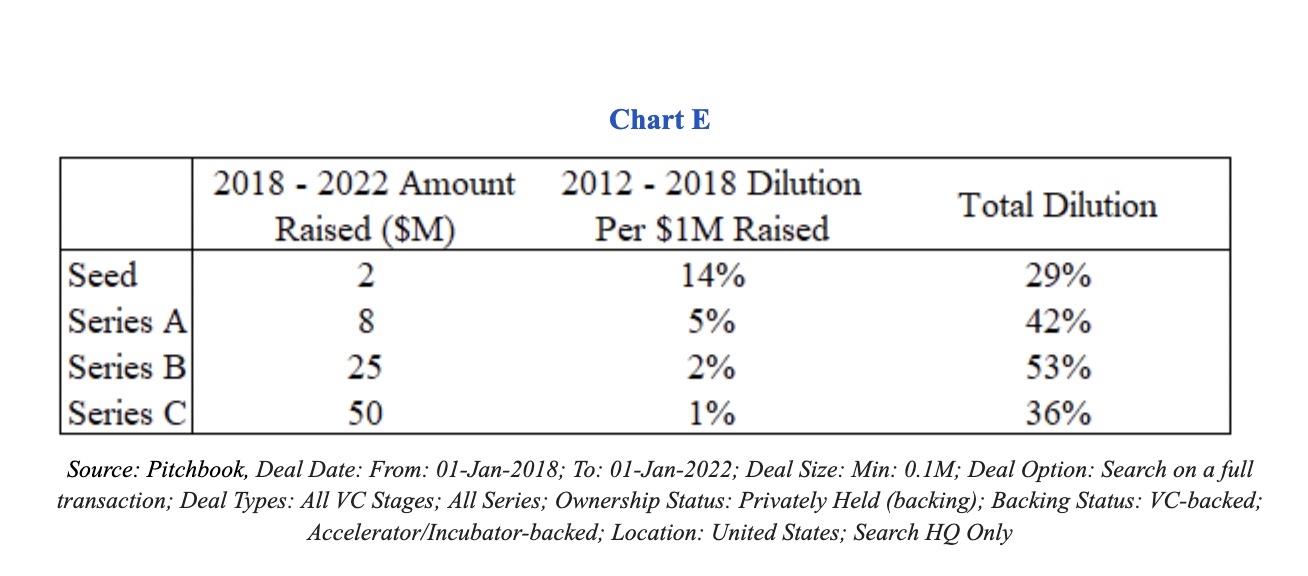

Let’s look at the historical data below (Chart E) to get some footing. If a company were to raise the same amount at each stage as the median during the 2018 to 2022 period, but do it in the valuation environment from 2012 to 2018, the founders would see significantly higher dilution.

Source: PitchBook data from 2012-2022. Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

In other words, if capital is more expensive, then you must either raise less capital or see significantly more dilution. The data shows that instead of getting your stake diluted about 20% at the Series B stage, equity holders would see 53% dilution for the same amount of capital raised. The short answer, therefore, is no.

If the environment today is more similar to the 2012 to 2018 time period than the last three years, “growth at all costs” will morph to “growth at reasonable costs.”

Founders will not want to see such a high level of dilution, and investors won’t either.

If we use our same assumption from above, after accounting for the subsequent dilution through the Series C, an investor’s 15% ownership will decrease to a measly 2.6%. Owning 2.6% versus 7.2% of a $380 million company translates to about $10 million of value compared with nearly $30 million of value.

Is planning for slower growth allowed?

As capital becomes more expensive, companies will face two options: Continue to raise sizable rounds as in recent years at the cost of much more dilution or raise less capital and grow at a more modest pace.

As we just learned, the potential increase in dilution may not be tolerable to investors or founders, so the answer is, yes, though it’s going to be an adjustment for investors, founders and employees alike.

If a company decides it wants to continue raising meaningful amounts of capital, as in our example above, in order to achieve its revenue growth targets, an investor will now have an estimated ownership of about 2.7%.

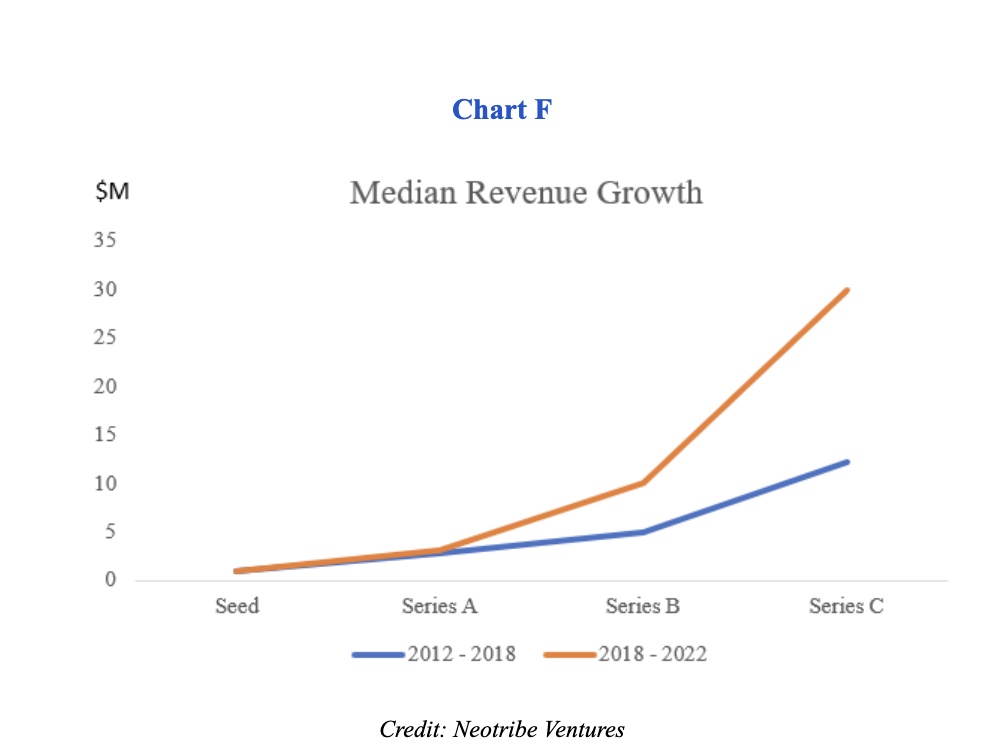

Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

As shown in Chart F, assuming the company follows the same trend as companies in the 2018-2022 time frame, its revenue at the Series C stage will be $30 million. Using the median valuation multiple of 10x from that period, we can assume a valuation of $300 million, and consequently, value to the investor of: 2.7% x $300 million = $8.1 million.

If the company instead decides to raise less capital and follow the median revenue trajectory from the 2012-2018 period, we can assume it’d have revenue of $12.2 million. Using the same multiple of 10x, we have a valuation of $122 million. Given that the company grew without raising as much capital, the investor will now own about 7.2%, which implies a value of $8.8 million.

While it may feel counterintuitive, given the recent market environment, the value of the equity for all parties — investors, founders and employees — in this scenario is higher in the more conservative growth scenario.

Using history as our guide, it is possible for equity owners to generate more value with more conservative growth, assuming they are able to reduce the impact of dilution. Therefore, this is a scenario all companies must consider when setting future budgets.

How can founders use this information for budgeting?

Let’s use an example to help you use this information. In this case, we have an enterprise software company that closed its seed round in June 2022. There is a high probability that its current financial plan has it running out of capital between December 2023 (i.e., 18 months) and June 2024 (i.e., 24 months). Why? Because, as noted, that’s the rule of thumb we’ve all lived under for the last several years.

Now, this company is looking to re-forecast its budget given the change in the environment. Let’s assume the company has runway through March 2024, the midpoint of our range. As we noted earlier, fundraises are taking longer to complete on average, and, if a company is low on liquidity, investors can be punitive with valuation. Therefore, the company wants to formally launch a fundraise with at least nine months of liquidity remaining. This implies it needs to start the fundraise in June 2023.

We should note that it’s common for enterprise software companies to see a majority of their sales in the fourth quarter, when their potential customers have money to either spend or lose once the new year comes.

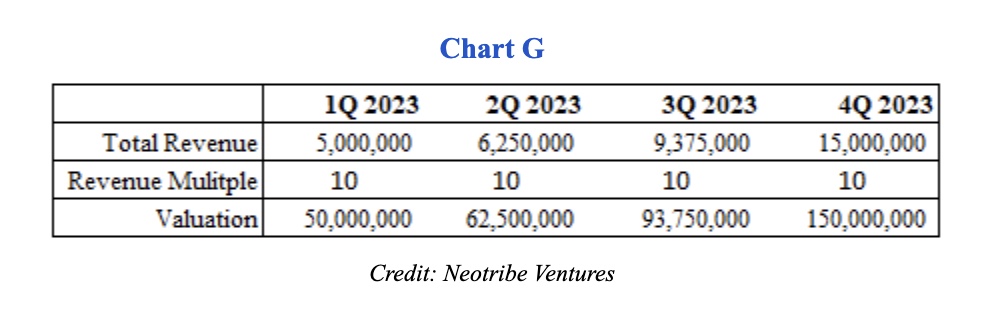

Let’s assume our company is still in “growth at all costs” mode: It wants to triple revenue in the year and is spending more aggressively to achieve this.

Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

As shown above in Chart G, based on this plan, our company is likely raising off revenue of about $6.25 million, which is the 2Q 2023 number. Continuing to use our 10x revenue multiple, this implies a valuation of $62.5 million.

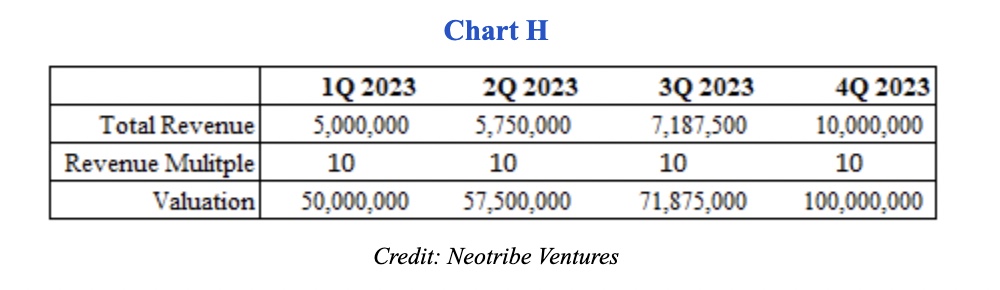

Consider what would happen if the company instead decides to limit sales and marketing expenses to extend runway and take advantage of 4Q growth (Chart H).

Image Credits: Neotribe Ventures

In this case, while its total growth in 2023 will be lower, the company could be raising capital off 4Q 2023 numbers instead. This implies a valuation of $100 million, or 60% higher, for its financing. By extending runway and waiting to launch the round until after it closes the books on the fourth quarter, the company can meaningfully impact its valuation in the next round.

The net result in this scenario is that the company may want to budget for a 27-month runway. Currently, 27 months still feels uncomfortable to say out loud (or type), but it may be the best path for this company.

Of course, there are many caveats. Investors may give companies credit for their future revenue targets, in which case, more aggressive targets can lift valuations. That said, companies should expect investors to be very skeptical about go-forward plans in this new environment.

Both investors and founders should be open to discussions

In volatile environments, canned responses or advice won’t hit the mark. The sooner we start having company-specific conversations and acknowledge that the cookie-cutter recipe for success isn’t sufficient, the better for all parties involved.

Revisit the VCisms you are holding as truth and determine if they are still applicable for your company given your cash runway, sales efficiency metrics, VC relationships (their ability to bridge you) and other considerations. Come up with different scenarios for your financial plan and don’t be afraid to make changes. Consider a “growth at reasonable costs” mindset, where you, in conjunction with your board, get to determine the definition of reasonable.

VCisms will likely never die, but it is time for a new era.