The SPAC route to listing on public markets was incredibly popular in 2020 and 2021, but many companies that took this avenue didn’t exactly fare well after going public. So why did consumer car rental marketplace Getaround decide to list by merging with a blank-check company?

To answer that question, we need to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

In hindsight, the 2020-2021 SPAC boom was unable to materially diminish the rising unicorn backlog. In 2022, unicorns continued to be minted faster than M&A and public offerings could convert their illiquid equity into liquid capital. It’s become a difficult time for high-priced startups: The traditional gateway to the public markets — the venerable public offering — remains closed, would-be acquirers are looking to trim costs instead of getting adventurous with their balance sheet and SPAC performance has proved abysmal.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Per SPAC Insider data, companies that merged with blank-check companies recently have seen their value fall sharply. SPAC combos worth $300 million to $2 billion in pro forma equity are off around 71% on a median basis since 2009, to pick a data point. Smaller blank-check combinations are down even more over the same time frame, while larger deals did slightly better.

Given such dreadful post-combination performance, why would Getaround hold to its course and complete its SPAC deal? If it hoped to avoid the fate of other companies that went the SPAC route, it did so in vain. The company closed yesterday at $1.37 per share and is off another 20% today at just $1.10 per share.

Despite its falling value, there’s a simple argument for Getaround’s SPAC deal. Let’s talk about it this morning, as the situation — and what the company chose — might help us understand a bit better if we could see more blank-check combinations in 2023.

Despite its falling value, there’s a simple argument for Getaround’s SPAC deal. Let’s talk about it this morning, as the situation — and what the company chose — might help us understand a bit better if we could see more blank-check combinations in 2023.

C.R.E.A.M.

Getaround raised lots of capital while private, but by this October, it was somewhat low on funds. This is our read of its financial reports through Q3 2022, which you can find here. With cash, cash equivalents and restricted cash of $30.8 million by the end of the third quarter, Getaround’s aggregate cash balance had halved since the start of 2022, when it had around $64.5 million on hand.

What’s more, the company had negative operating cash flow of $63.2 million in the first nine months of 2022. (A bridge loan of $27.1 million helped it avoid a more irksome cash crunch before the SPAC deal closed.) If we compare the company’s 2022 cash burn and its cash balance at the end of Q3, it is not hard to see that Getaround needed to raise cash to keep going.

If you agree with our argument thus far, we can also agree that the company’s choice in late 2022 was not whether to raise capital but simply which mechanism to leverage in order to boost its cash reserves. This is where our work gets a bit more speculative.

Here’s how we vet Getaround’s options after rereading its operating results through the third quarter of this year:

- Equity raise from private investors: Unlikely, given modest revenue decline in the first nine months of 2022 compared with the same period in 2021.

- Debt: Unlikely or too expensive to be feasible, as the company’s growth profile is limited, and its asset base modest partly due to its asset-light business formula.

- Sale of the business: Possible, but given the choice to raise capital via a SPAC, perhaps not too likely.

What options does that leave Getaround with? Raising cash by another method or shuttering the doors when its accounts run dry.

And what method of raising capital was available to the company? A SPAC. Which worked, by the way, as far as raising cash is concerned: as Getaround noted, the transaction for the “pioneer of the digital carsharing transformation” saw it raise “approximately $228 million.” That’s a lot of money.

Could the company have raised that amount of money from other means at a pro forma equity valuation — at least originally — of $1.18 billion. Probably not.

For Getaround, then, the SPAC route makes good sense from a cash management perspective. It got the bag, went public in the same movement and can now execute its operating plan without going-concern worries. Not bad, yeah?

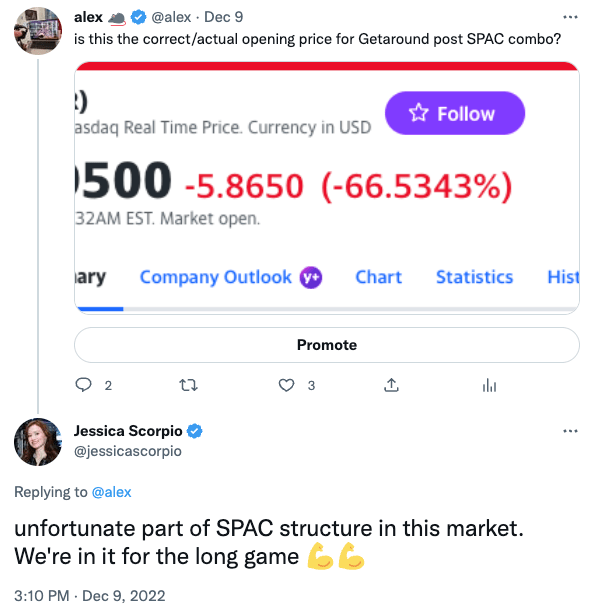

Our read of the situation fits neatly into what one of the company’s co-founders, Jessica Scorpio, told your scribbler on Twitter the day Getaround completed its SPAC deal and began to trade:

There are downsides to consider. With much of Getaround’s value now deleted, the company has less currency to play with when it comes to compensating employees. Retention could become an issue.

The obvious rejoinder to that concern is that, with layoffs in tech rising generally today, staff are more likely to stay put than in recent years. That could provide Getaround with some breathing room to rebuild its worth and therefore its employment value proposition. We’ll learn more on that front when Getaround drops Q4 2022 numbers in early 2023.

Sticking to criticisms of the deal, if any retail investor bought into the company’s debut and got their face ripped off, well, that’s not good.

For now, the Getaround SPAC deal is best understood through the lens of “cash rules everything around me,” as without cash, a business instantly asphyxiates. Getaround isn’t, per our understanding of the deal and the company’s financial position pre-deal, in such danger right now.

Perhaps the company will prove the markets wrong, return to growth and move toward profitability, rebuilding its equity value in the process. We’ll see, but if your options are SPAC or die, choosing to live just makes sense.

With so many VC-backed private tech companies on a timer while tech valuations remain depressed and IPOs far off, perhaps this actually isn’t the last SPAC deal we’ll see in the foreseeable future. Other former startups might also need the cash badly enough to brave the blank-check gauntlet.