If someone offers you a seat on a rocket, you don’t ask which seat. So goes one of Silicon Valley’s favorite platitudes, one that you can trace back (at a minimum) to former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and former Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg.

The idea is that if you are given a shot at working on something new and big, you just say yes and sort out where you fit in the organization later.

The chestnut can apply in other circumstances. For example, if I was building a Very Cool Company that was perhaps set to break out and become the Next Big Thing, you might be more concerned about getting some of your capital into the business (a seat on my business rocket ship) than precisely how the business is run (asking which seat you are buying).

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Making a big bet on the future without knowing all the details can, per the Sandberg example, work out well. It can also … not. As with many business cliches, the rocket-seat philosophy is frequently over-applied. Instead of being reasonable advice to be bold in the face of uncertainty, it can also be used to make witless choices appear reasonable.

Back to our investing variation of the concept: Let’s say that you were given minimal information on a hot startup, one that was already backed by folks you know, and had to make a call about whether to invest in the business in a short time window.

In our thought experiment here, let’s say that the company was operating in a murky legal gray area, did not have a normal board of directors, and was run, more or less, by one bloke. Is this the chance to snag a seat on the rocket or the chance to put a lot of capital on the grill?

In our thought experiment here, let’s say that the company was operating in a murky legal gray area, did not have a normal board of directors, and was run, more or less, by one bloke. Is this the chance to snag a seat on the rocket or the chance to put a lot of capital on the grill?

In 2021, a lot of investors decided that asking where precisely their capital might sit on various startup rockets was not worth it. Given the competition among investors for deal allocation and a market valuing tech revenue at sky-high levels, the choice might have made some sense.

And some of those wagers might work out. But we’re also seeing an increasing tide of whoopsies from investors, folks now reverting to more old-fashioned investing norms, like expecting reasonable governance and more corporate information.

It’s too late for FTX, it seems. The former high-flying crypto exchange worth a few dozen billion dollars at one point is now in bankruptcy proceedings, and its new CEO is livid with how it was run. We’ll get into the nitty-gritty below, but given the lax investing standards we saw during the 2020-2021 startup boom, the implosion of FTX feels less like an exception to recent norms and more the final result of folks buying not rocket-ship seating, but instead the rights to watch someone who lacks any proper training fly the machine from the wings.

What investors bought into with their FTX stakes

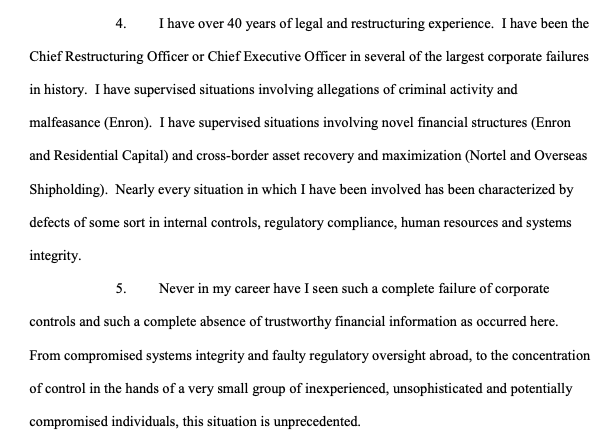

In a filing relating to the Chapter 11 bankruptcy concerning FTX and its myriad subsidiaries, the mood of the company’s new CEO, John J. Ray III, is not hard to parse.

Best known for his work during the aftermath of Enron’s crumbling, here’s a sampling of what Ray had to say about his experience and what he found at FTX:

Image Credits: FTX

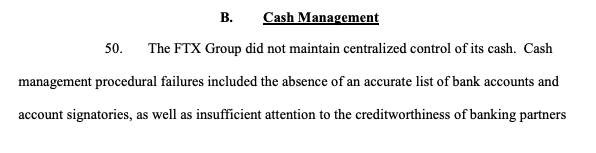

To understand just how broken it appears that FTX was, observe the following excerpts from the same document regarding cash:

Image Credits: FTX

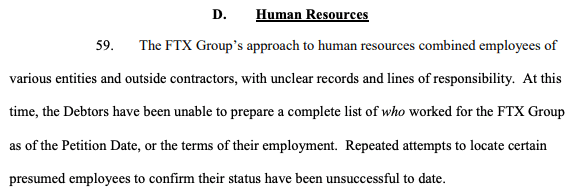

Human resources:

Image Credits: FTX

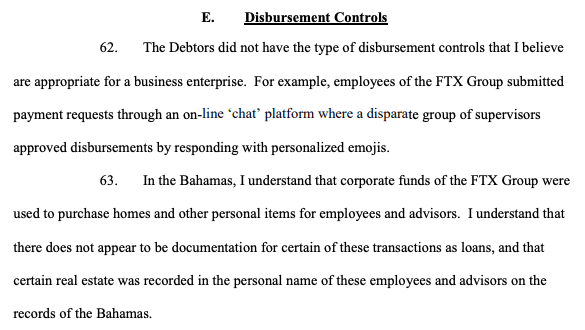

Spending:

Image Credits: FTX

Care of digital assets:

Image Credits: FTX

Care of assets more generally:

Image Credits: FTX

And decision-making:

Image Credits: FTX

What is Ray up to? Getting some governance in place, to start:

Image Credits: FTX

It turns out that some of the bedrock ideas when it comes to building and running companies were, in fact, good ideas. Having a board is good. Having more than one person in charge is good. That sort of thing.

The unicorn era that reached its apex last year was a period of time in which founders were invincible, investors were merely fungible capital sources, a new economy was set to be born, and everyone was in a hurry. Well, this is what comes out of fast and loose investing.

It’s notable how different things were last year compared to prior startup decades. VCs once invested in founders and demanded that they hire an external CEO to help them run the company. Schmidt, whom we mentioned at the top, was one such CEO. Google wound up doing pretty well. So did Facebook, where Sandberg went to be the adult in the boardroom.

Shocking as it may seem, playing League of Legends during investor meetings is not a good measure of business competence or founder trustworthiness. The above filing speaks volumes about FTX, sure, but also how quickly the venture class dropped their own advice to secure a seat on a rocket they were hoping would only go up.

It did not.