If you are running R&D at a large appliance manufacturer, you have a challenge.

You typically make products in enormous quantities at pretty slim margins. In order to recoup your development, tooling and launch marketing costs, you need to create and sell a huge number of products. To ensure that that’s possible, you’d probably end up doing a bunch of user and market research to ascertain that you have the highest chance of success with your products.

That makes sense, but the very business model itself means that it’s hard to do something truly risky, which in turn means that mainstream manufacturers rarely come up with anything genuinely innovative.

If there was a mushroom fruiting appliance, would a lot more people regularly be growing mushrooms at home? There was only one way to find out: to build one and to try and sell it.

That’s where FirstBuild comes in. If you’re a small appliances nerd, you may have seen its Opal nugget ice maker, the studio’s first big breakthrough; the Mella mushroom fruiting chamber; its indoor pizza oven; or the Arden indoor smoker. I spoke with André Zdanow, president at FirstBuild, to figure out where these ideas came from and how the studio is working to try to replicate those successes.

“The most famous example is probably the Opal nugget ice maker. At first, it wasn’t actually a product at all — it was a technology being worked on in the refrigeration division of GE Appliances,” Zdanow said, explaining that it turned out to be a head-scratcher. They wanted to put the “nugget ice” into a fridge but weren’t able to figure out exactly what the market size would be for such a thing. “It’s actually really complicated to put the technology into a refrigerator. In other words, it was really a great idea that engineers had been toying around with for years, but in the context of the focus and economics of a multibillion-dollar company, it wasn’t something that they could focus on.”

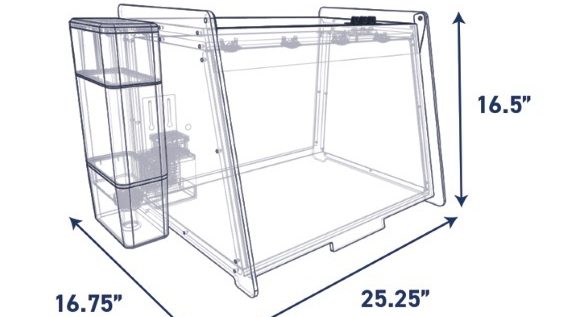

The Opal nugget ice maker was FirstBuild’s first commercial success. Image Credits: FirstBuild

In a parallel universe, that tech would never have seen the light of day, but instead, the engineers came to FirstBuild and wondered what would happen if they put the tech in a separate appliance, rather than into a full-size refrigerator.

“We see lots of people go to the store and buy this type of ice. They call it Sonic ice or hospital ice. We decided to develop a prototype and see if people want it to be just an ice maker,” Zdanow explained. That was the genesis of the FirstBuild lab’s success. “It started with crude concepts that looked like an ice maker but had nugget ice in it. From there, it progressed through industrial design and ultimately to a $2.7 million crowdfunding campaign on Kickstarter back in 2015.”

In terms of market validation, $2.7 million of crowdfunding money is a pretty compelling argument, and the company concluded that this was an opportunity to use FirstBuild as a way to do high-risk in-house R&D, where failure was more tolerated — expected, even — while doing rapid-iteration hardware manufacturing.

“Ultimately, we got the validation we needed. There was a market, customers participated in the development and design of the product, and then they stepped up with their pocketbooks and said, ‘Hey, I will buy that thing,'” Zdanow said. FirstBuild was hyperfocused on the Opal ice maker as a result, and development on other products ground to a halt. “The Opal ice maker became its own enterprise. When I showed up in 2018, FirstBuild was struggling to manage the ice maker, and it wasn’t focused on product development or innovation. It just had become an Opal startup. I showed up, and said, ‘Hey, can I take that nugget ice maker from you? I’ll pay you in royalties.'”

FirstBuild created an indoor open-hearth oven and then repurposed the tech to create an indoor smoker (pictured above). Image Credits: FirstBuild

GE, in turn, had at that point been bought by industrial conglomerate Haier Appliances, and Zdanow was friends with CEO Kevin Nolan. Zdanow told me that Nolan agreed that the large corporation wasn’t that good at entrepreneurship — and Zdanow saw his opportunity. He took the ice maker and built a small appliances business unit within GE Appliances. When the ice maker “graduated” into its own business unit, it showed that the appliance manufacturer could do what it was best at — manufacturing and distribution — and FirstBuild was ready to start looking at what the next thing could be.

“Product ideas come from a number of different places. Some of them could be internal, some are external. But the important thing is that the validation is always with the world at large. Sometimes it’s rudimentary — a ‘wouldn’t it be cool if … ‘ sketch or a concept video. We try to speak with the community at large and figure out if we are looking at a solution for a problem that you have. We want to know if our consumers care about the thing,” Zdanow said.

The heart of FirstBuild is a couple of makerspaces and an appetite for a lot of trial and error. Today, the team enjoys being at arms-length from GE Appliances with a lot of creative freedom to figure out how to do product development. The team ranges from 20 to 25 full-time members, depending on how much manufacturing FirstBuild is doing, and another 20 to 25 hourly workers that largely help with manufacturing and assembly.

An example product

A great example of how products come to life is the Mella mushroom fruiting chamber. I have a lot of experience as a prototype engineer, so I put on a hat from a previous life before the fruiting chamber arrived. I realized that the device itself is exceedingly simple; a halfway decent mechanical engineer with access to a well-equipped makerspace could make one in a day or so. The sides and lid are cut acrylic. The hinges and fans and electronics are all very well designed, but nothing you’d need an advanced manufacturing facility for.

The Mella mushroom chamber is … very simple indeed. Image Credits: FirstBuild (opens in a new window)

The only curiosity was the water tank on the side of the device; that’s a well-designed, sophisticated part with injection-molded parts, sealing rings and design features. A quick look at the FirstBuild website solves the mystery: The well-designed tank is well designed for a reason; it actually belongs to the Opal nugget ice maker — it is the side tank:

Using parts of one product in another. Image Credits: FirstBuild (opens in a new window)

It’s the kind of thing you rarely see in mass-manufactured products, but hardware hackers love this sort of thing. Why would you design a whole new part when there’s a perfectly fine existing part you can adapt? If you’ve ever seen the Ikea hackers website, you know what I’m talking about. When you have the luxury of running a prototype lab and you have access to parts and features from other products your lab is making? Genius.

And, of course, if the Mella mushroom fruiting chamber finds a large-scale audience, it, too will graduate and go through a “design for manufacture” (DFM) process. At the moment, the team can build them by the hundreds or thousands — if it wants to start building them by the tens of thousands or beyond, it stops being efficient to have humans hand-assemble the products.

“We have a micro-factory because we wanted to be able to go from proof of concept to prototype to maybe early production,” Zdanow said. “If we’re going to end-to-end do all the fabrication, we’re best equipped in a sweet spot of 500 to 2,000 units per year. We could hybridize and have sub-assemblies that come from somewhere else and maybe scale to from 2,000 to 10,000 units, but if we do that we are really pushing our limits then. To give you an example: We just graduated another product, an indoor open-hearth oven. We start with flat sheet metal, we cut it and we bend it, we assemble it and we test it. And that really has a cap of 1,000 to 2,000 units when we’re actually running the supply chain through the makerspace.”

Concepts galore

At any given time, FirstBuild is making a ton of products, working on prototypes and creating new concepts. For every success that sucks up a lot of the organization’s attention, the ideation is at risk — but the team is pushing hard to ensure that the pipeline stays active.

“We had two KPIs when we started. We wanted to try to have one product to the validation stage per month. In other words, we wanted to come up with 12 product concepts a year. The idea by year two was we’d like one of those find some some commercial opportunity, or a life beyond our labs. By 2018, we actually set a goal of hitting breakeven. We’re not just a cost center anymore,” Zdanow said. “Opal was a proof of how we take something that is at its production limits, and we move it out. That way we can stay true to our Product Development Innovation mandate — and we’re not allowed to be a cost center.”

Steven Fox and Danny Carballo with the Mella mushroom fruiting chamber. Image Credits: FirstBuild

The mushroom fruiting chamber was an example of a product that hung in the balance for a long time. It isn’t a fully automated grower like Shrooly, for example. It came out of a need the team found. Using spray-and-grow kits from companies like North Spore is a fun and easy way to grow edible mushrooms at home. Mushrooms, however, need the right amount of light, CO2 and especially humidity. The latter, in particular, is tricky: Mushrooms love 85%+ humidity, and humans generally don’t. So, having a grow chamber makes sense, but there’s a huge question there: Are these mushroom kits popular enough to warrant an appliance? And moreover, what is the chicken and what is the egg: If there was a mushroom fruiting appliance, would a lot more people regularly be growing mushrooms at home?

There was only one way to find out: to build one and to try and sell it. The company built a prototype and threw it on Indiegogo. More than 1,200 people voted with their dollars — more than 600,000 of them — and FirstBuild had its answer.

“Almost every week that went by I was like, ‘When are we gonna kill it?'” Zdanow said, admitting he was wrong. “Then we sold one. And then we sold 10. And then we sold 100. And then suddenly we were selling thousands of them.”

The company used the same approach with the Arden indoor pellet smoker. A crazy idea, perhaps — who smokes things indoors? — but again, $750,000 worth of pre-orders on Indiegogo later, it turned out that this, too, was a hit.

“The Arden smoker was multiple years in development. It actually all started out because one of our employees bought an old GE refrigerator and decided to turn it into a smoker,” Zdanow explained, suggesting that the smoker became possible because of the indoor open-hearth Monogram pizza oven the company is moving into production. “To make an open-hearth oven indoors, we had to develop a way to catalyze smoke and make it safe — it is an oven without a door. The FirstBuild team was having fun using this old GE refrigerator as a smoker. We would have barbecue Wednesdays. Then it started getting rainy and cold, and someone had the idea: ‘What if we just cannibalize the catalyst out of the indoor hearth oven and put it on the smoker?'”

The FirstBuild team with the Mella fruiting chamber. Image Credits: FirstBuild

The team built the smoker so they could continue with the barbecues, and people kept asking whether they were going to launch it as a product. The product development continued, and over the years, the team came up with something that could potentially work.

“We built some foam-core mock-ups and invited community members in. We asked what they wanted — ‘How big do you want it to be? Do you want it in the wall? Do you want it on the counter?’ and it continued to be a labor of love. Over a couple of years, we locked in that design we really honed in on how the product performed. We brought in experts in smoking,” Zdanow said, which reminds me that the GE connection means that the team knows how to make appliances — and has access to a bunch of experts.

The team suggests that part of its superpower is to great opportunity due to its location. The first makerspace is on the University of Louisville campus, which means it has access to a lot of young engineers. They can help manufacture, prototype and develop. FirstBuild’s more experienced engineers have come through the Edison training program. The makerspace has a commercially rated kitchen on site as well, so it can test things out.

“I can take a product off the factory and walk into our commercial kitchen, which has a health rating, and we’ve got people that are certified food handlers. We can put it to work, host an event with something that we just built in the back,” Zdanow explained. “It’s about that essence of co-creating. We start that process and engage in that process continually online both on our platform and on social like YouTube and Instagram. But where the rubber meets the road is when we have an opportunity to work with consumers.”

A hackathon at the FirstBuild space. Image Credits: FirstBuild

By keeping a prototyping mindset, the FirstBuild team is able to go from ideas to prototypes in consumer homes in about 100 days. That’s almost unheard of in product development circles — tooling for injection molding alone can take almost that long.

In a nutshell, the team has built a machine that can create functional prototypes, and then test whether the market wants it. If the answer is yes, the team can choose to do small-batch manufacturing or go through another design-for-manufacture sprint to put the product into scale production.

And Zdanow and his team, in turn, have the ultimate dream jobs for people who love doing product development, so there’s that.