What’s better: growing quickly or making lots of money?

The answer, in startup terms, is both. But because there is a natural tension between growth (which usually comes with incremental costs, often in advance of new revenues) and profitability (allowing revenue to further extend its coverage of operating costs), most startups lean more on the growth side of the equation.

It’s not hard to understand why. Venture investors provide capital that often greatly exceeds a startup’s revenue base, allowing the company to hire and market aggressively — and build, we hasten to add — in hopes of far-larger future scale at the cost of near-term profitability.

The tradeoff between growth and profitability is often detailed in the so-called Rule of 40. Indeed, the rubric that combines a growth metric (measured in year-over-year terms) and a profitability result (measured in percent-of-revenue terms) in hopes of the sum meeting or exceeding 40 has generated derivative metrics for companies of a particular age or segment.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Naturally, the Rule of 40 is not something that applies to, say, pre-revenue startups hoping to raise a pre-seed round. It’s a metric that applies to startups that are generating revenues at a sufficient scale to make the numbers reasonable; no one cares if you can meet the Rule of 40 while tripling your revenue from $1 to $3 per year, but if you are expanding your revenues from $1 million to $3 million per year, the rule is likely something you’ll be measured against.

Now that venture markets are in retreat and public markets have been revalued, there’s been some push for startups to change their posture, trading some growth now for smaller deficits. A flight to quality, some call it.

Now that venture markets are in retreat and public markets have been revalued, there’s been some push for startups to change their posture, trading some growth now for smaller deficits. A flight to quality, some call it.

We’d call it a rebalancing away from quicker growth and staggering losses toward merely rapid growth and less cash burn.

Battery Ventures recently dropped a new report (the “State of the OpenCloud 2022”) that includes some fascinating data on the profit/growth conversation. It’s something that we’ve touched on repeatedly here at TechCrunch as both venture investors and their public-market cognates have shaken up their valuation models.

Below we’re dissecting the data and parsing commentary from Battery’s Dharmesh Thakker, who answered questions for us on a few finer points. To work!

Growth versus profit

Saying that tech companies should focus more on profitability than growth in the near term is controversial; some venture investors don’t consider the change in proffered advice to be real. After all, companies will struggle to generate a venture-style return if they slow their growth and therefore limit their implied future cash flows, right?

Perhaps. There’s good logic to that argument. However, Battery argues with compelling data that at least in the near term, there’s real evidence that to create more value today, at least a slight change in priority among venture-backed companies is reasonable. (Note that we’re discussing cloud companies here, meaning that the following discussion doesn’t apply to, say, biotech companies.)

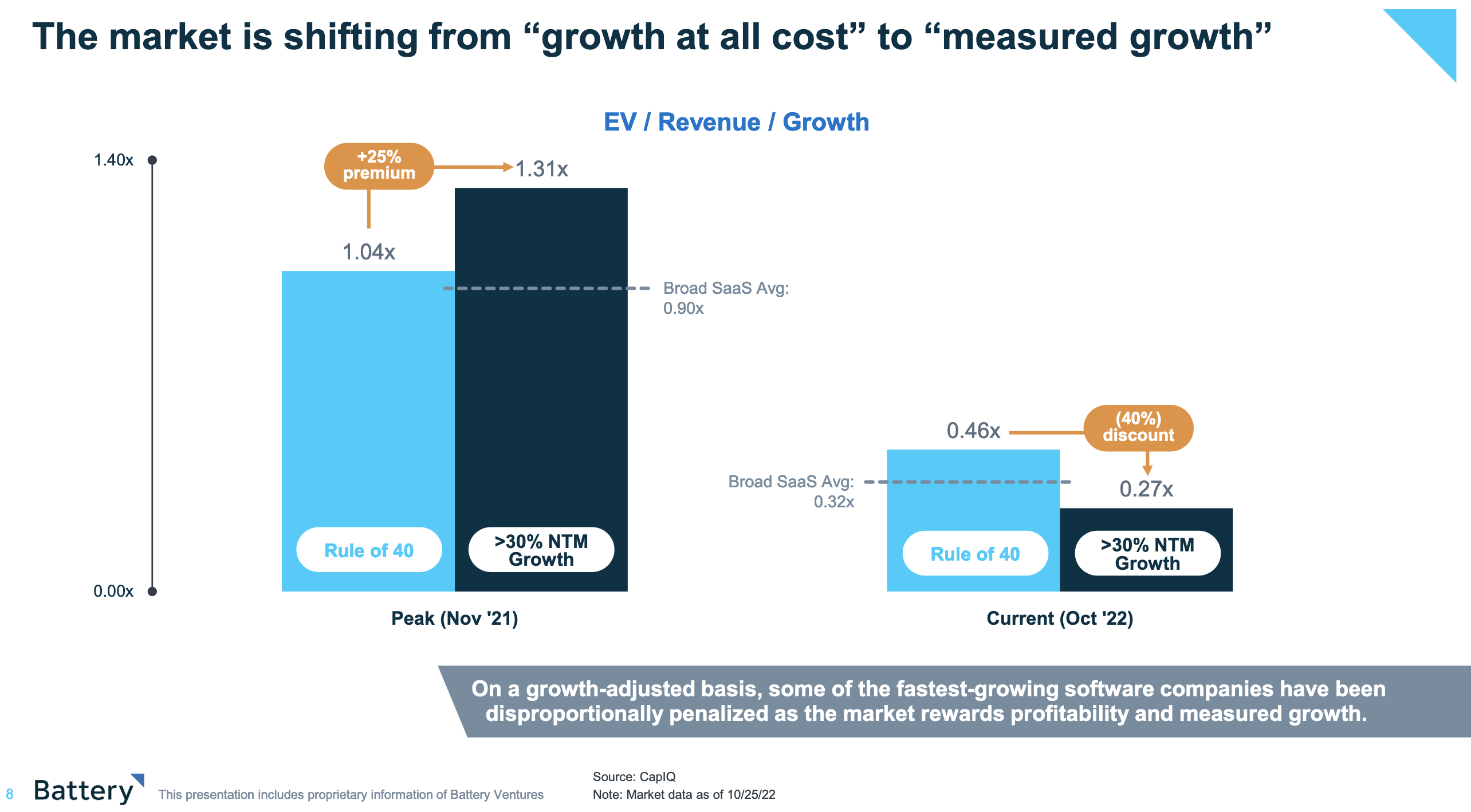

How so? The following chart calculates the same metric against two cohorts of startups at two different times. In each set of columns, we can see companies that met the Rule of 40 compared to those with faster growth rates, and, presumably, less profitability.

Image Credits: Battery Ventures

The metric in use here is company value divided by revenue divided by growth rate. As you can quickly tell, this metric is a derivative of something that we’re intimately familiar with, namely revenue multiples. We often look at companies that, say, are worth $1 billion and have a $50 million revenue run rate. For that company, we could say that it had a revenue multiple of 20x.

There’s great nuance in how to calculate revenue multiples, including, to pick one pertinent example, whether for the company value portion of the calculation we use market cap (share value multiplied by the total number of shares) or enterprise value (market cap minus cash plus debt, loosely). But the chart above, instead of noodling on how to calculate revenue multiples, adds another bit of data: growth.

A company, for example, with a 40x revenue multiple growing at 40% would generate an “EV/revenue/growth” figure of 1.0x. As we can see in the two bars on the left, at the peak of 2021, companies that grew faster than those with more balanced profit and growth were valued more richly.

And on the right, we can see, in contrast, that companies that meet the Rule of 40 are valued more richly than their faster-growing but less profitable peers today. The question becomes whether the information — sourced from S&P Capital IQ — applies directly to startups. Regardless, we can see in the chart both the multiples compression of the last few quarters and the investor shift from preferring growth over profits to a more balanced blend.

Naturally, the two bars on the right side of the above chart will flex with time as investors react to changing market conditions. But for now, it’s clear that not only are tech companies simply worth less than before, but also that investors have changed their tune on what they are willing to pay more for.

New times, new rules

If you are wondering why investors changed their minds, you won’t be surprised to hear that it is mostly due to macroeconomic conditions that look completely different compared to the peak of 2021 and years prior. Battery Ventures general partner Dharmesh Thakker, whose team authored the report we are looking at today, notes the following:

With near-zero interest rates over the last few years, many companies got comfortable raising large amounts of venture money and burning through it quickly to grow to significant scale before optimizing for profits. Now, with interest rates and the cost of capital suddenly much higher, the cost of borrowing and raising more dollars is untenable — and founders are focused on measured growth and efficiency much earlier in their growth cycle.

For late-stage startups, especially those that hope to have a shot at an IPO, it means that priorities need to be reshuffled. The bottom line, per Thakker, is that “the market is sending a clear message to tech companies and founders that growth alone isn’t enough. That growth also needs to be efficient and profitable.”

The investor thinks that cloud scaleups are well placed to adapt to this new context.

“By focusing on efficient sales and marketing, product-led or product-assisted growth, and using open-source and cloud-based R&D, founders are pursuing a faster path to profitability. This will ultimately create higher-quality durable enterprises in the long run. I’m still incredibly optimistic about the cloud,” Thakker said.

Thakker’s optimism about one of Battery’s favorite verticals may be warranted — after all, it’s about a sector that enjoys undeniable long-term tailwinds. But even cloud services aren’t immune to worsened market conditions: Major cloud infrastructure players saw their growth slow last quarter, and rising energy costs are raising questions about cloud service margins in Europe. This means that other sectors might suffer even more, especially outside of the SaaS realm.

As a matter of fact, SaaS is increasingly the domain of product-led growth rather than sales-led growth (although Battery is more agnostic on that front, saying that there’s “no one-size-fits-all” in that respect). But either way, it often delivers higher margins.

In contrast, sectors that are still highly driven by marketing spend might have a harder time than their enterprise peers in achieving the kind of metrics that an IPO will require — a topic on which Battery’s report gave us more food for thought.