It appears battery startup SES’ investors are quite happy with its first earnings report. The company went public in February via a SPAC merger, and to no one’s surprise, reported a loss.

And its investors don’t seem to mind. Its shares, while still trading below its SPAC merger price, were up 16.7% at $6.15 at the time of writing, outpacing broader markets gains earlier in the day.

The company posted an operating loss of $19.2 million in the first quarter quarter. General and administrative costs accounted for much of that, at $15.1 million, while R&D ate up another $4.1 million. It reported a net loss of $27 million, or $0.12 per share.

At the end of the quarter, SES had $426 million in cash and expects to have enough runway to enter commercial production in 2025.

Battery startups like SES all lose money, and it looks like the company is losing just enough to stay in the race, but not so much that it would burn through its reserves before it has a commercial product. Developing and commercializing a new battery is a long, expensive game and investors seem to be happy with SES’ balancing act. If it spent too much, it would risk bankruptcy, of course. And if it didn’t spend enough, it would risk falling behind its competitors.

Investors also appear to be rewarding other battery startups that have gone public via SPAC in the last year, including Solid Power, which is up 10%, and QuantumScape, which is up 13%.

The balance of general expenses versus R&D suggests that while work continues on its lithium-metal technology, an increasing amount of the company’s cash hoard is being spent on building larger scale facilities in the ramp up to commercial production.

Indeed, in an interview earlier this week, CEO Qichao Hu told TechCrunch the company is continuing to develop its Shanghai Giga site and another facility in Korea, which was announced earlier this year. Currently, the Shanghai site has an annual production capacity of 0.2 GWh, which Hu said is “more than enough” for what they are making right now.

“In March, we started building cells for Hyundai and Honda out of our Shanghai facility, and for GM out of Korea facility,” he said.

The company is testing these cells in-house and then sharing the data with partners. By first quarter next year, Hu expects to begin shipping cells directly to automotive companies so they can do their own testing.

“To serve different OEMs, and also for geopolitics, the Shanghai facility can serve the China-inclusive markets, and then Korea will serve the China-free markets, especially North America and Europe,” he said.

“For now, at least A sample, B sample, C sample, we plan to do everything in-house,” Hu said. “When we get to the really large scale, the tens of gigawatt hours, then we might partner with someone like LG or larger.”

A hybrid approach

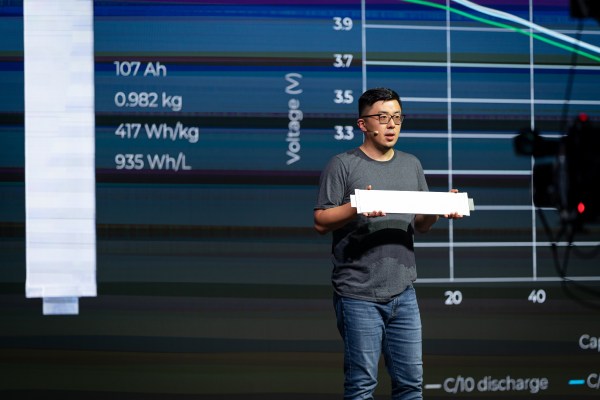

Unlike some other startups that are going all-in on solid state batteries, SES is developing a lithium-metal battery that ditches the graphite cathode while tweaking the typical liquid electrolyte. In SES’ battery, the electrolyte is what’s known as a solvent-in-salt, meaning it’s mostly made of salt with some liquid solvent interspersed. The company says it is non-volatile and “self extinguishing” in the event of a fire.

To eliminate graphite, SES paints the anode side with a proprietary coating to allow lithium to accumulate when the battery is being charged without forming harmful dendrites that can puncture the separator and cause a short circuit.

SES claims that its hybrid lithium-metal approach allows it to hit manufacturing milestones faster than all-solid-state lithium-metal competitors since its similar to the way batteries are made today.

The company is developing its technology to accept a range of different cathodes. There’s been a lot of talk in recent months about automakers seeking alternative (read: cheaper) cathodes that omit nickel and cobalt, which were already expensive before they recently shot up in price.

The main alternative is lithium-iron-phosphate, which is cheaper but also heavier and stores less energy. SES has a parallel development track for that material.

Confronting inflation

For battery companies like SES, the future is both winsome and worrisome. After slogging through lean years of grinding R&D work, the frontrunners are being lavished with funding, which frees them to start chasing the scale needed by the automotive industry.

But commodity prices are rising, thanks in part to Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine, and also due to the stunning surge in demand driven by the sudden shift to electric vehicles. Meanwhile, automakers are expecting battery costs to continue dropping from about $100 per kWh at the cell level to $80 and eventually $60.

Better manufacturing can help bring costs down by limiting the number of cells that have to be scrapped, but the looming squeeze has Hu considering other revenue options, including battery as a service.

“If the price target keeps coming down, and the raw material price goes up, this is not sustainable for anybody. To make it more sustainable, we have to make the end user pay more, because the [cost of the] raw material is going up,” he said.

“For example, in an internal combustion engine car, when the price of oil goes up, you pay more at the gas station,” he explained. “That’s normal. Every raw material is going up. Also, to make these batteries safer, the cost is higher, so users should pay more. But of course, we have to do it in a way that so the cost of total ownership is higher, but the cost of entry is lower. So then you lease the battery.”

The battery-as-a-service approach is being tested by Chinese automaker NIO and Vietnamese automaker Vinfast, but SES appears to be the first battery startup to float the idea. Whether it catches on with consumers, though, remains to be seen.

While people have grown accustomed to mileage limits associated with leasing vehicles, they don’t often like restrictions on their daily activities. Mobile phone plans, for example, have moved away from buckets of minutes, texts and data to unlimited plans.

With EVs, consumers still have concerns about range anxiety, and adding more restrictions with mileage limits probably won’t help matters. It may take years for people to get past their anxieties, and commodity prices may have come back to earth by then.