Financial projections are essential for any business, but in the case of tech startups, a financial model is one of the most important and overlooked tools available to a founder.

Venture-backed startups work on risky, aggressive capital deployment, often operating at a loss for years as they pursue expansion and market dominance. This means that runway is a critical KPI that founders need to keep an eye on for every single financial decision.

Aggressive spending should translate into aggressive growth: Revenue might jump 20% or 30% month over month, which makes runway estimation an ever-moving target. Being able to expand the team a month earlier can make a tremendous difference in the long run, or cutting down expenses quickly can save the company from running out of money.

When milestones and deadlines are directly driven by your finances, you put yourself in a great position to iterate.

However, few founders build themselves the tools to help make those decisions. We connect with hundreds of founders every month, and the most common mistakes we see include:

- They created a financial model only to satisfy investors but don’t use it for their day-to-day operations.

- They are using a revenue-driven financial model, rather than a driver-based model.

In the fast-paced world of startups, quick and educated decisions are critical. Take a look at this example scenario.

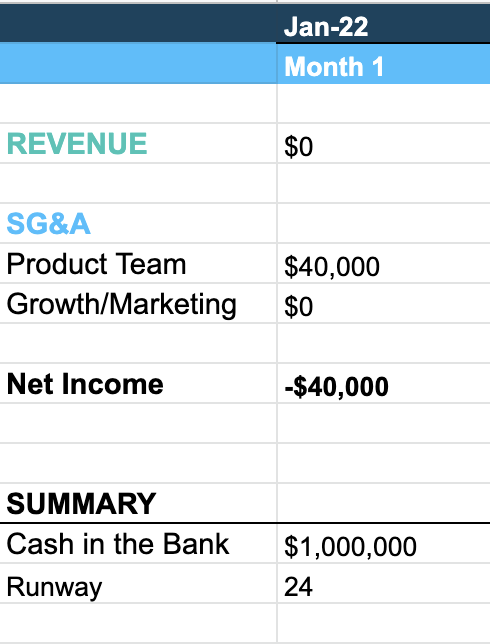

A company is looking to raise a $1 million seed round to finish building and launching its product. It can set a burn rate target of $40,000/month so that the capital lasts roughly 24 months.

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

A safe cushion is to assume that new investor negotiations will take about six months, so by month 18, the company should be in a position to begin pitching to the next round of investors.

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

Where does the company need to be when it wants to raise money? How much of the product should be ready? How much revenue will it have? How many customers? How much will it cost to bring those customers?

The founders need to make sure their capital deployment takes all of those variables into account. A miscalculation can translate into spending too little (and failing to launch the product on time) or spending too much (and not being able to close the next round before money runs out). The stakes are high.

The problem is, in my experience, seed-stage founders are rarely thinking of these targets when they define how much money they want to raise or how they want to spend it.

Creating a model that you actually use

The most common problem I see is entrepreneurs think of the financial model as “homework,” so they prepare it to satisfy an investor request or to fill a slide in the pitch deck.

At the pre-seed or seed stage, it’s impossible for the model to predict revenue accurately. So for an early-stage company, the model should serve two main purposes:

- Oversight of the runway and letting you make financial decisions to ensure you reach your next funding milestone.

- Laying the grounds for the future of your business: understanding how fast your company can grow and which KPIs affect it.

Runway

Any sophisticated investor will understand that at the seed stage, there isn’t enough information to come up with accurate revenue projections, so the projected revenue of the financial model is not what they are after.

What they want to see is that the founder understands at least the basics of their business’ financials. The importance of the model at this stage is, again, that delicate balance of capital raised, burn rate and runway.

I’ve seen many founders target an arbitrary number for their round without actually looking into how long that capital will last, or whether or not traction will suffice to secure additional capital.

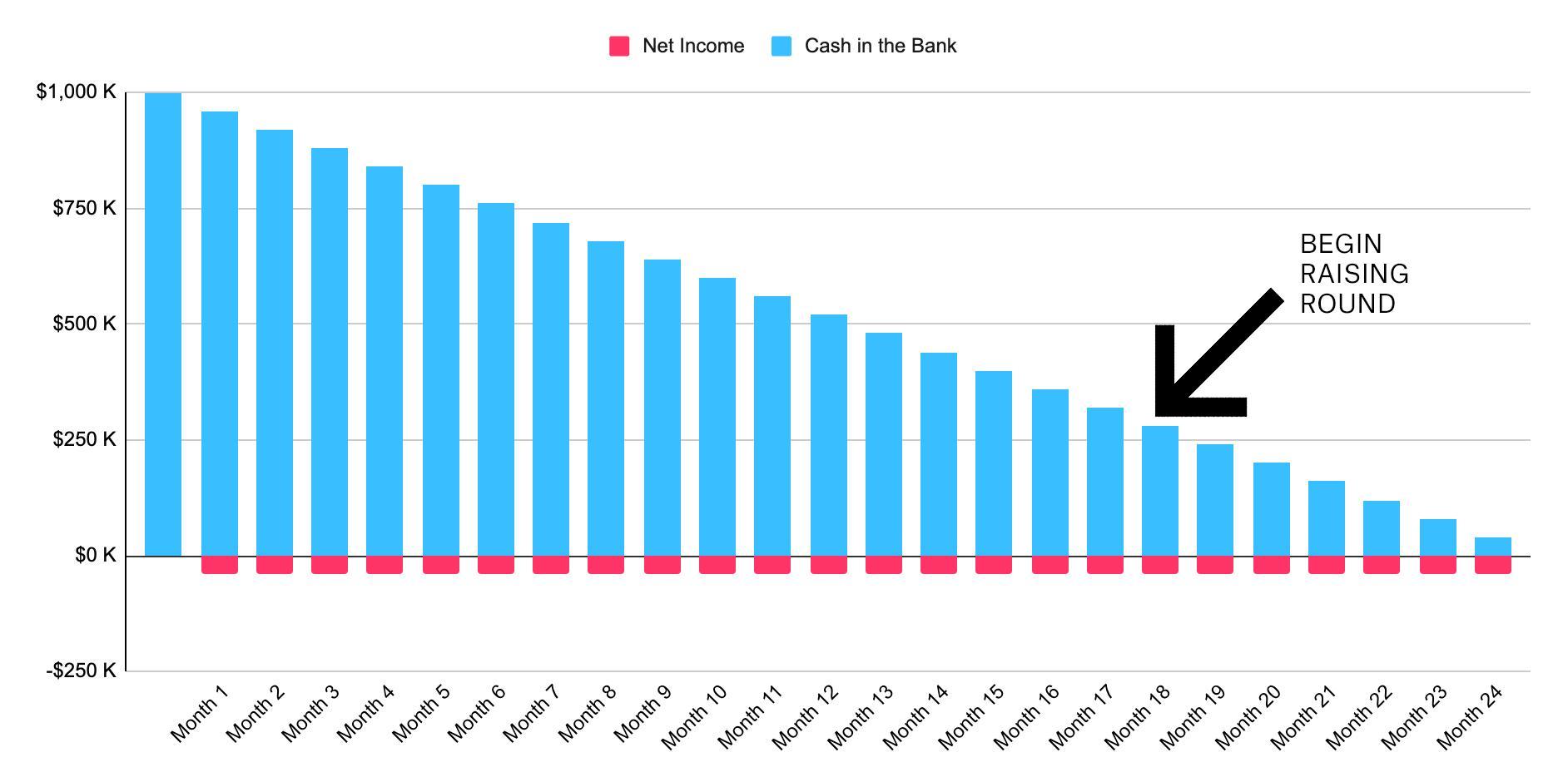

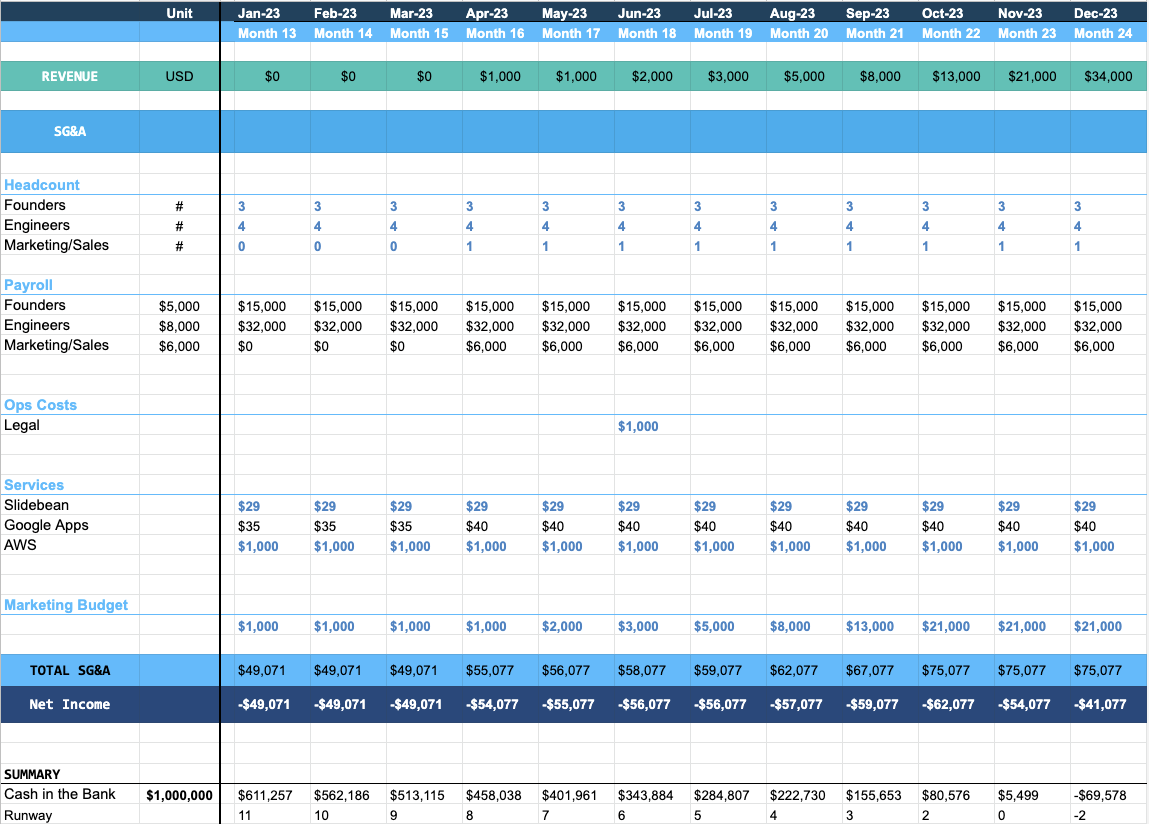

Year 1:

A simple financial spreadsheet. The blue numbers are inputs and black numbers are formula results. Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

You can create a relatively simple spreadsheet that accounts for:

- How quickly you scale your team and their salaries.

- The services you’ll be paying for — if you are keeping track of your headcount, you can use it to estimate the cost of your SaaS platforms more accurately.

- When you plan to launch the platform and how new revenue affects your runway.

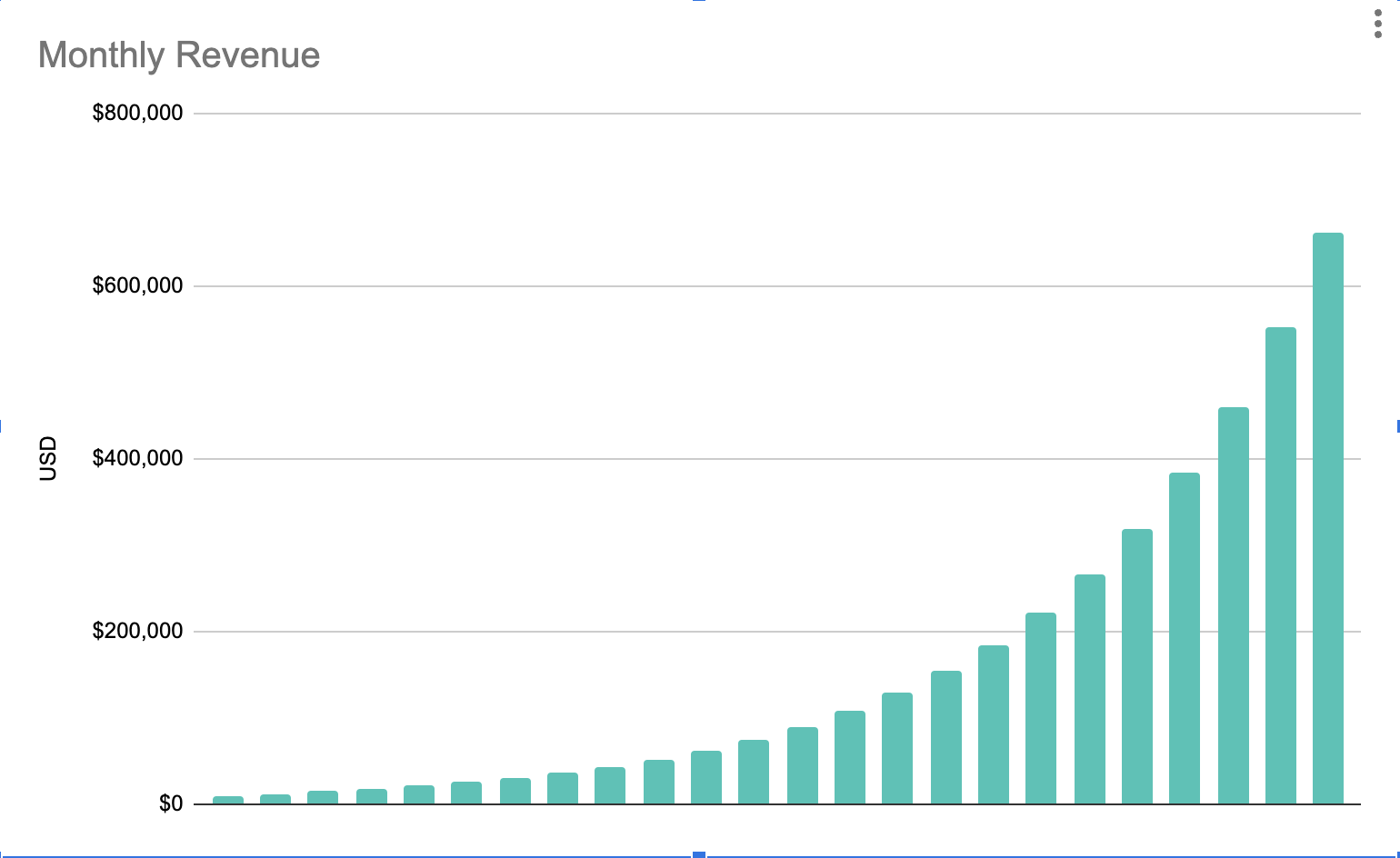

Year 2:

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

In this scenario, for example, the company is bound to run out of capital by November 2023, which means they ought to start raising capital around May or June.

Now, is the company ready to raise their next round of capital?

KPIs and fundraising

For a SaaS business, a common milestone for a Series A round is annual run-rate revenue of $1.5 million to $2 million. This means that it first needs enough seed capital to reach that milestone.

Different startups will have different requirements, but it’s key to ensure the money will last long enough to reach your next milestone.

In our scenario, this company will be approaching fundraising with $2,000/month in revenue and an operating cost of $55,000+, which might not be enough to get the next round of investors excited.

So now the spreadsheet becomes a tool to model scenarios. For example:

- Is there a way to launch the product sooner by perhaps ramping up engineer hiring earlier?

- Is there a way to build the product with fewer employees?

- Is there a way to increase revenue faster?

When milestones and deadlines are directly driven by your finances, you put yourself in a great position to iterate. There’s nothing like the pressure of running out of money. And if you can have visibility on that 12 months in advance, you can plan accordingly.

Evolving the model

As you continue to use a spreadsheet like this for your day-to-day decisions, you’ll soon find other ways to calibrate the model to reality and make even more informed decisions.

By the time the company reaches Series B, the financial model should be able to accurately predict revenue for a month with a margin of error of less than 5%. This means that the operations team should be using it regularly for all financial decisions (hiring, expansion, growth budget). It also means the model will be a determining factor in the company’s capacity to raise that Series B and any future round of funding.

The sooner you start building this tool, the better.

Again, understanding what happens with the company’s financials considering these assumptions is extremely valuable and essential. Moreover, once you are able to convert the first few customers, you will have a real CAC number to plug in to your spreadsheet to use for future assumptions.

Working with variables like this from the get-go will provide you with a learning curve and allow you to add more complexity to your assumptions as the business evolves.

Growth-based models versus driver-based models

Another incredibly common mistake I see founders make is having their models scale on growth rate rather than by an expense driver.

For example, a founder might assume that they will launch their product, make $5,000 in revenue in the first month and then scale that growth by 20% month over month for the next 24 months. That’s fantastic hockey-stick growth but shows little to no understanding of the actions, strategies and expenses that will cause the company to grow every month.

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

In this scenario, for example, there’s an exponential growth in revenue. So is the marketing budget scaling exponentially as well? Is the sales team also scaling exponentially? If growth is exponential and expenses are linear, this might reflect a lack of understanding of what the growth drivers are. Still, most models I come across use a similar approach.

More importantly, it’s easy to just assume 20% month-on-month growth. It’s much harder to understand what is going to drive it and budget for accordingly. This is why I believe the best approach to modeling is driver-based.

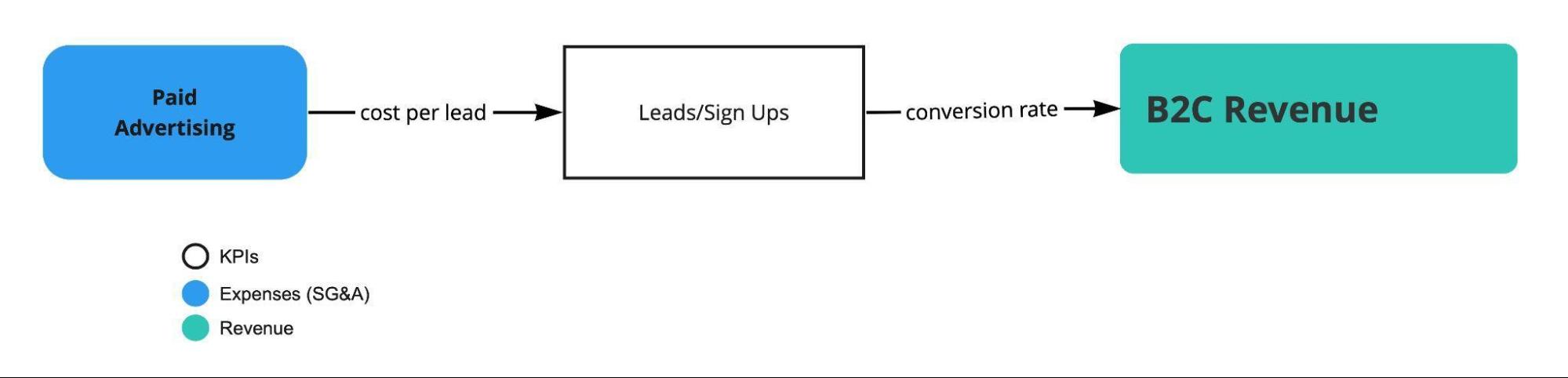

In a B2C SaaS business that plans to grow via search ads, for example, you would build the model using the paid advertising budget as a driver. That “paid advertising” budget is an expense. That budget is then converted into leads or sign-ups at a cost per click. Likewise, those leads are converted into paid customers at a given conversion rate.

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

The advantage of breaking this down is not only that you are already accounting for that expense, but it will also estimate conversion based on two very universal KPIs: CPC and conversion rate.

You can find benchmark references for what those numbers might be and estimate using real-life data. And the moment you launch your platform, you will have real numbers to plug in to the model and confirm that your scaling assumptions still make sense, or if your budget is enough.

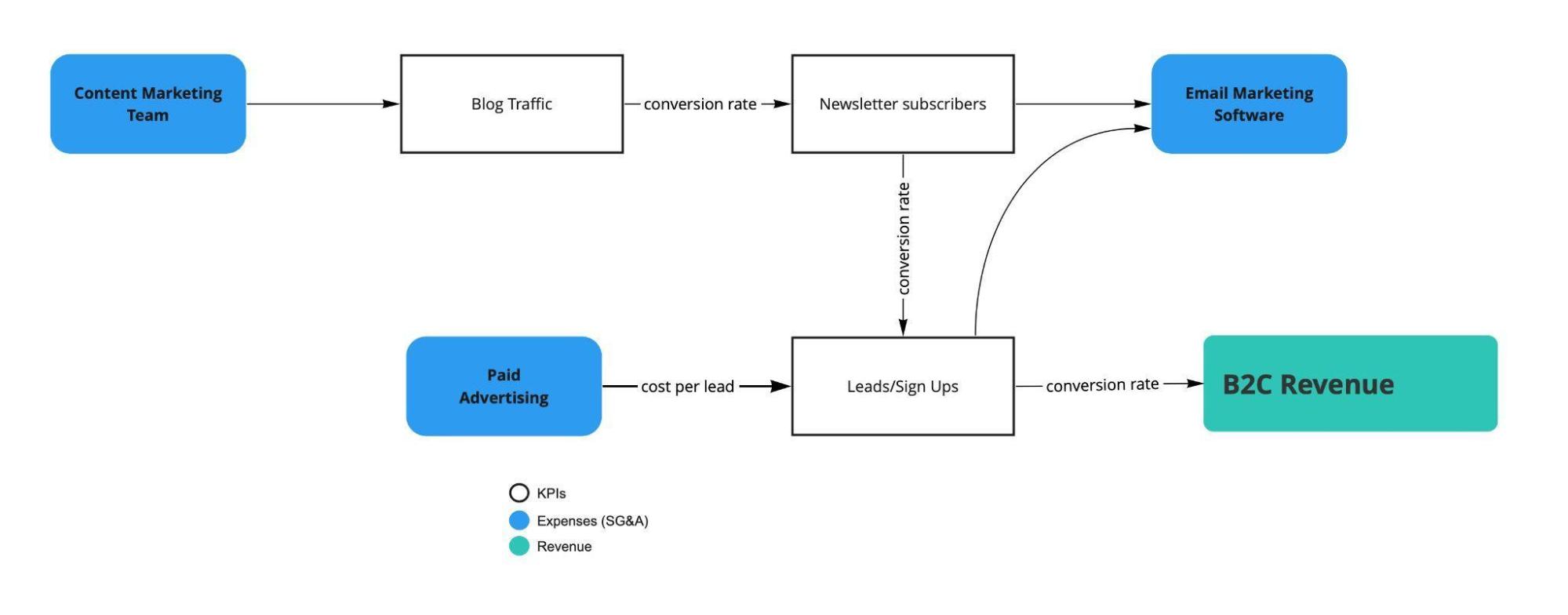

All these numbers can be used to estimate many other factors about the business, such as:

- You could sum the total number of leads across time to estimate how much your email marketing software will cost in the future.

- As you experiment with new channels, you can add them into the same funnels or even create new funnels.

Image Credits: Jose Cayasso

Here’s a basic financial model template, very similar to the one we used in this article, that you can use as a starting point for these estimations.

Once again, the key is to understand that there are no direct controls to change your revenue estimates. Everything is controlled from your drivers, which in this case are expenses you need to account for.