It’s hard to imagine a bigger game than Horizon: Forbidden West. The second in the open-world series following the adventures of Aloy, future cave woman, in a post-apocalyptic landscape populated by robot dinosaurs, it’s literally difficult for me to think of things the developers could include that they didn’t at least try to. In an age of enormous games, this one attempts to be the most enormous of all — and whether it succeeds depends largely on your appetite for the type of game it offers up so very much of.

I’ll save you a little time with a TL;DR: If you liked the first game, and the prospect of a lot more of it sounds good, stop reading and start playing. If you’re looking for something different, however, this definitely ain’t it. And as a showcase of the “next generation” it’s a baffling mix of gorgeous graphics and decade-old gameplay concepts that haven’t been given so much as a fresh coat of face paint (unlike everyone else in the game).

Horizon: Forbidden West (hereafter referred to as HFW) is a game large enough that by the time I’d started putting together this review, more than 20 hours into it, I had not yet even encountered the things the review guidelines warned against including. When I finished the intro, I realized that what I thought was the intro was actually just the intro to the intro; now I see that at that moment, I was only just beginning the real intro, and after 15 hours had arrived at The Game.

(Minor spoilers for HFW follow, along with major spoilers for the previous title.)

But I’m getting ahead of myself. HFW is the sequel to Horizon: Zero Dawn, a PS4 flagship title from Guerilla Games that adopted the now familiar open-world scheme pioneered and repeated regularly by Ubisoft. Look at the map, go to a point of interest, unlock new quests and collectibles to get you to the next part of the map, rinse and repeat for about a hundred hours.

Yet in spite of the open-world fatigue already setting in back in 2017, the original game provided something fresh — largely because of a highly original setting and story. People wanted to explore the vast world, not simply to check things off a list, but because every location they visited or enemy they overcame added new tidbits to the surprisingly rich and complete lore.

The trick Guerilla had to pull off was to continue to make that story interesting after the big reveal: that humanity had essentially destroyed itself, leaving behind an AI to manage the terraformation of the ruined Earth — an AI that self-destructed, along with the fragile balance of mankind with machines. After the revelation of thousands of years of history, of Aloy’s identity as a clone of the system’s designer, and her victory over the rogue AI element Hades, what possible surprises could remain?

I’ll steer clear of spoilers, but suffice it to say that the story continues, perhaps without quite the aplomb of the original but with an expanded and satisfying scope that answers many questions and confirms many speculations. And it does so at great, great length and with a truly stupefying amount of distractions.

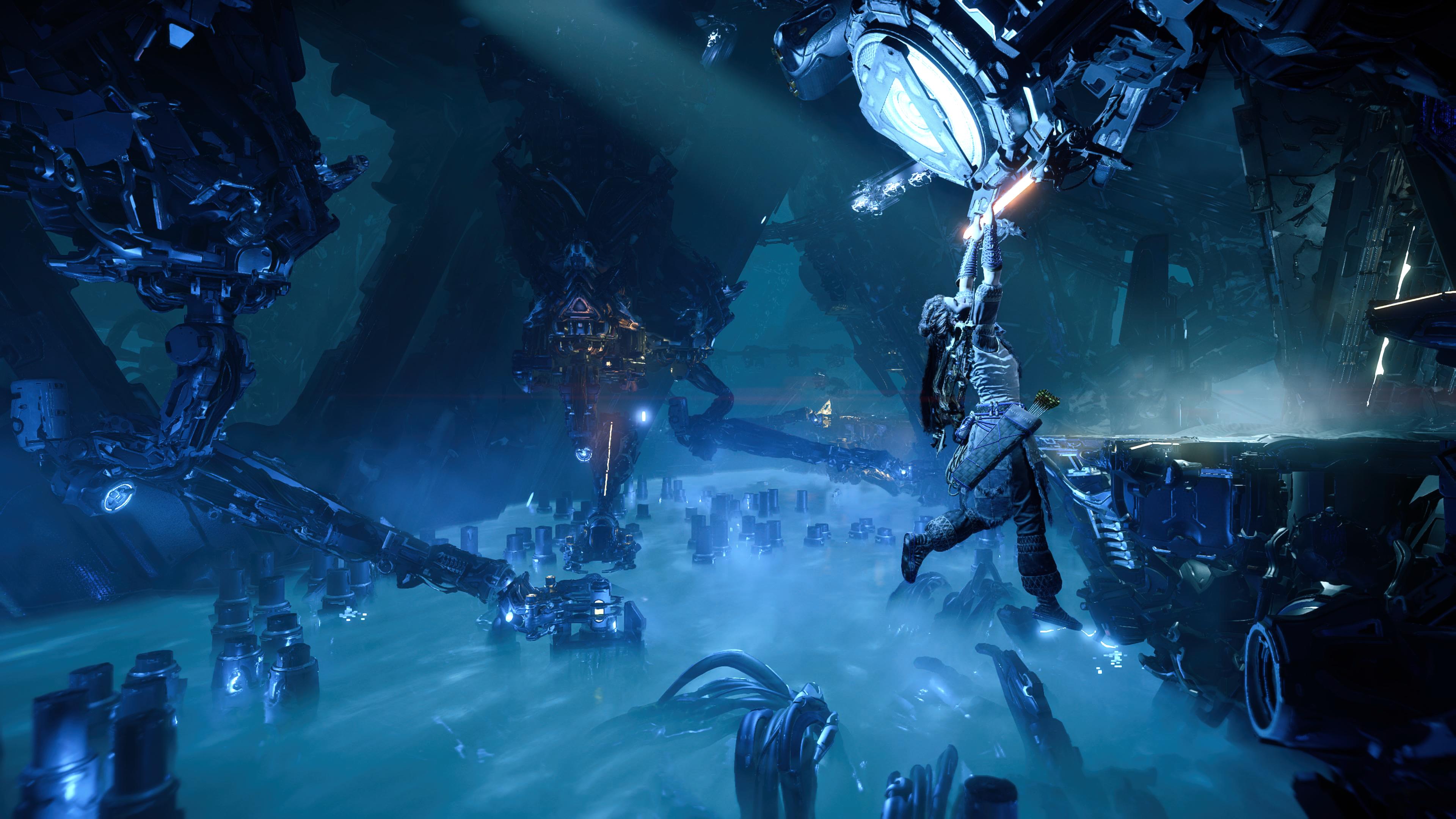

An eye-watering showcase

Image Credits: Sony

It has to be said right off the bat that HFW looks phenomenal. The world is beautifully sculpted, large and varied. A dozen times I stopped at some vista I’d arrived at as part of the normal course of things, thinking “now this is the header image,” before finding another even more amazing view half an hour later.

Each environment you travel through is convincingly rendered in extreme detail, from tribe towns to the many natural biomes and ruins. Funnily enough it’s the “modern” areas that feel the fakest. I played the game on PS5 in “Performance” mode, which aims for a higher frame rate, rather than the 4K resolution, which added a bit of detail but was fatal to playability. Even at 1080p, sometimes I could barely believe what I was seeing (by which I mean the opposite: that it was very believable). The draw distance and realistic fog and lighting are particularly lovely.

If you can wait to play this on PS5, I’d recommend it. I didn’t play on PS4 but I expect it will be considerably less enjoyable, given how large a role the graphics and short load times played in my opinion of the game.

The characters too are the best I’ve seen, with the possible exception of God of War — but that game had a much more limited cast. In HFW, you have dozens — hundreds — of NPCs wandering around, offering quests, getting attacked, and so on, and they’re all extremely well rendered. The people you chat with to take on jobs or buy items are all highly individual even within regions. And the characters you travel with along the way are more detailed than the main characters just about any other game.

[gallery ids="2268350,2268351,2268347,2268349,2271776"]

The level of care put into making the future a diverse place is also easy to appreciate. All different kinds of folks are to be found in every part of the game: the sunny plains peopled by frond-wearing leafniks don’t tend toward anything but a slimmer body type… probably because they spend most of their time gardening, compared with the beefy beer-swilling miners of Chainscrape. Bigotry is on display between clans and lifestyles, to be sure, but no one discriminates based on race, gender or age. I will say the tribal paint and style occasionally rubbed me the wrong way, but I don’t know if I’m being oversensitive here. It’s sci-fi fantasy cave-dweller stuff, to be sure, but I’ll leave it to others (Eurogamer’s Malindy Hatfield raises an eyebrow) to discuss whether it feels inappropriate.

Sadly, the graphics are really where the “next generation” thing starts and ends. The other aspects of the game, while more numerous and better rendered than ever before, are almost exactly what we’ve been playing in open world games for a decade and more.

(However, I would like to thank the developers for the wide and granular set of accessibility and difficulty options. Whatever my criticisms, the game is an impressive and exciting world that should be able to be enjoyed by anyone, and they’ve done a lot to make that possible.)

World of Side Quests

Sorry… our princess is in another castle. And can you grab me 7 weasel hearts, I mean apex burrower circulators? Image Credits: Sony

To give you a starting idea of what it’s like to play HFW, there are 17 categories of quests.

Your usual “main” and “side” quests, sure, but also “errands,” “contracts” and self-assigned “jobs,” rebel hideouts and camps (tracked separately), combat challenges, hunting sites… the list goes on.

The map is littered with icons representing the haunts of various robosaurs, which you’ll need to harvest in order to craft and improve the dozen or so weapons you’ll want to have on hand at all times — depending on the dominant element of the region you’re in, your armor’s bonuses, your chosen upgrade path, etc.

Then there are the ancient ruins, full of block-pushing and platforming that would be right at home in an N64 game; the futuristic dungeons known as Cauldrons, which are largely linear obstacle courses that grant you new dino-hacking abilities; dozens of side quests that grant skill points and new items (some useful, many redundant); the requisite tabletop game-within-a-game with collectible pieces. There’s even an attempt at a sort of kart racer, riding through the wastelands blasting away at your fellow racers and collecting pickups like new weapons and speed boosts.

Everywhere you go, quests and landmarks spring up like the invasive red sprouts taking over the land. It seems around every corner some caravan has been attacked, a loved one is missing, a town threatened, a glow in the hills feared. Aloy cheerfully agrees to help everyone despite a hard deadline being placed on the end of the world.

It helps that every interaction and every quest is fully and quite well voiced and acted; while frequently a matter of “go here and fight this,” these have the advantage of names and faces and consequences, however fleeting. I helped a small town of the leaf-loving farmers fight off some raiders after locating some metal they needed to make weapons, a quest out of the RPG bargain bin if I ever heard of one. But I enjoyed it because I liked how the world-weary town chief, who looked and sounded like a real dude, extemporized philosophically about the meaning of the white flowers his townsfolk plant when they die, and gave me his (terrible) bow at the end of it all.

There are dozens and dozens of such experiences, each one as skippable as the next, but each also given a level of detail that would only be gestured at in most other games. They may not be particularly original, or even well written, but they’re fleshed out to a remarkable degree. I suppose it’s only fair to say that this does also seem like something of a next-generation feature. (Some other open-world games, like Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, have done this to some degree but it hasn’t landed the way it does here.)

Image Credits: Sony

Sure, in God of War every quest would actually matter — but here I find we have the ultimate and much improved form of the side quests we’ve been enduring for decades. You’re not taking orders from a community board and turning the mollusc scrapings or raccoon tails in to a faceless Adventurer’s Guild. You’re helping this guy, whose realistic face and matching voice make him seem like an actual character, find out what happened to his wife. It feels different, even if it’s fundamentally the same “kill 8 were-rats in the cellar” fare.

That said, for those who found the last game’s interminable clan warfare and familiar RPG conflicts unbearable, be warned there’s a lot more of it here. What’s in the Forbidden West? Drama! The main quest suffers from side quest syndrome as well: Wherever you need to accomplish something significant, there’s some warchief or mayor who wants to you clear out those robo-cattle rustlers first, or oust a rival, or retrieve the whatsit from the ruins.

Yeah, yeah… Image Credits: Sony

It’s not that these are all bad, exactly — like the others, they’re well acted and detailed, though indifferently written — but there’s a constant sense of “come on, let’s get on with it!” as yet another two-minute conversation begins between some town elders on how this flame-haired outlander doesn’t respect their traditions…but honored Makito, our people need such and such… and so on and so forth. Like a network TV show (and the original game, and most open-world games), HFW doles out its enjoyable main story beats a handful at a time between large portions of filler.

Part of my annoyance at this, however, is down to the fact that I was reviewing the game under time pressure. This is not a game to play four hours at a time, but 45 minutes: sit down, finish that side quest you’re near, make some progress toward the next main story goal, harvest a few critters and upgrade your bow, then shut it down and go to dinner. You could probably do that for a year straight and never run out of things to do. It’s when you spend too long in the game at once you start seeing the time suck for what it is.

But the game remains the same

Image Credits: Sony

Where I found myself losing my patience with HFW, despite its beauty, was in the stale AI, combat and progression systems.

The AI really is disappointing, recalling the dumbest humans and wildlife of any generation you’d like to sample. Guards go from half-blind automatons to eagle-eyed killing machines and back; allies have a death wish but unlimited health; the critters compete to throw themselves under the feet of your robotic steed, which itself stops short every 40 feet when it encounters a pebble it can’t step over. The robotic dinos are at least convincing as wild monsters, though simple.

Combat is more strategic than tactical, since after the opening gambit of taking a pot shot or two or a sneak attack, it feels sloppy and chaotic. That can sometimes be fun, but the inability to lock onto an enemy and the extremely large durations and areas of effect of many incoming attacks (and their habit of coming from offscreen) mean you spend a lot of time blindly rolling around the battlefield before spinning around to take a few potshots. When you take aim, it can be very hard to tell whether the glowing thing you’re aiming at is a weak spot or just plain glowing — and while you’re trying to take a precise shot, you lose all peripheral vision and another enemy blindsides you. Fortunately you’re quite durable as long as you don’t get one-shotted (which does happen).

Improving in this game is almost all stats: No matter how good you are, you won’t stand a chance with your starter bow after a few hours because its base damage is too low. Improvements to weapons and armor are all “number go up”: +10% ice damage, +12% plasma defense, and so on.

Damn if it doesn’t look good, though. Image Credits: Sony

The skill tree you invest in is very traditional: a mix of numbers and situational skills like firing three arrows at once or temporarily doing more elemental damage. I rarely used these skills in my playthrough as in the chaos of combat I couldn’t remember which was equipped on what weapon or even how to activate my selected “valor surge,” a sort of ultimate. I realize that sounds very noobish, but to me it’s more a question of having too many tools with unclear benefits. It’s nice to have a super-arrow I can shoot from stealth, but it’s less than useless in a boss fight. Conversely, investing in melee seems equally worthless when you rarely can get enough hits off on a tough enemy to make it worthwhile before being slapped across the landscape. So you have to be a generalist, and end up having choice paralysis.

And throughout the game there’s a sense of old-school gaming “logic” clashing with the next-gen visuals. Missions are rigidly defined and scripted, no out of the box thinking wanted or allowed. There’s really no freedom to do things your own way — there’s almost always one way to do everything. And though you have many optional activities, those activities have no options.

In these ways HFW feels very much like the games we’ve all been playing for 20 years, the final and grandest version of a proven and enjoyable, if tired, set of gameplay elements.

To me this is a warning for the next generation of gaming, which we hear a lot about in terms of new levels of freedom, interactivity, AI and other aspects, but so far have received mostly the same old thing with a highly attractive coat of paint on top. The graphics are welcome, for sure — it makes the characters more real, the world more convincing. But the game remains the same.

That said, it’s a fun game and a substantial romp that fans of the original will love. With huge games coming out every month or two, however, I hope that one will come along that one-ups its predecessors not simply in scope and visual richness, but in ideas and rewarding gameplay.