Tech sees differently, and can fuse multiple types of data we can’t even perceive: lidar, IR, ultrasonic and so on. Metalenz, maker of highly compact “2D” cameras for advanced sensing, hopes to bring polarized light into the mix for security and safety with its PolarEyes tech.

Polarization isn’t a quality of light that’s often paid much attention. It has to do with the orientation of the photon’s movement as it waves its way through the air, and generally you can get the info you need from light without checking its polarization. But that doesn’t mean it’s useless.

“Polarization generally gets thrown out, but it really can tell you something about what the objects you’re looking at are made out of. And it can find contrast that normal cameras can’t see,” said Metalenz co-founder and CEO Rob Devlin. “In healthcare, it’s been used historically to tell whether a cell is cancerous or not — the color and intensity don’t change in the visible light, but looking at polarization it works.”

But polarized light cameras are pretty much only found in medical or industrial settings where their specific qualities are needed, and therefore the devices that do it are fantastically expensive and rather large. Not the kind of thing you would want clipped to the top of your laptop screen, even if you could afford the six-figure price.

The advance Metalenz made when I wrote about them last year was reliably and inexpensively manufacturing the complex micro-scale 3D optical features to make a tiny but effective camera on a chip. These devices, Devlin said, are currently coming to market as part of an industrial 3D sensing module, partly in partnership with STMicroelectronics. But the polarization thing has more consumer-relevant applications.

“Polarization in facial recognition tells you whether you’re looking at real human skin, or a silicone mask, or a high-quality photo or something. In automotive settings, you can detect black ice, it’s really difficult with normal cameras but it jumps out with polarization,” said Devlin.

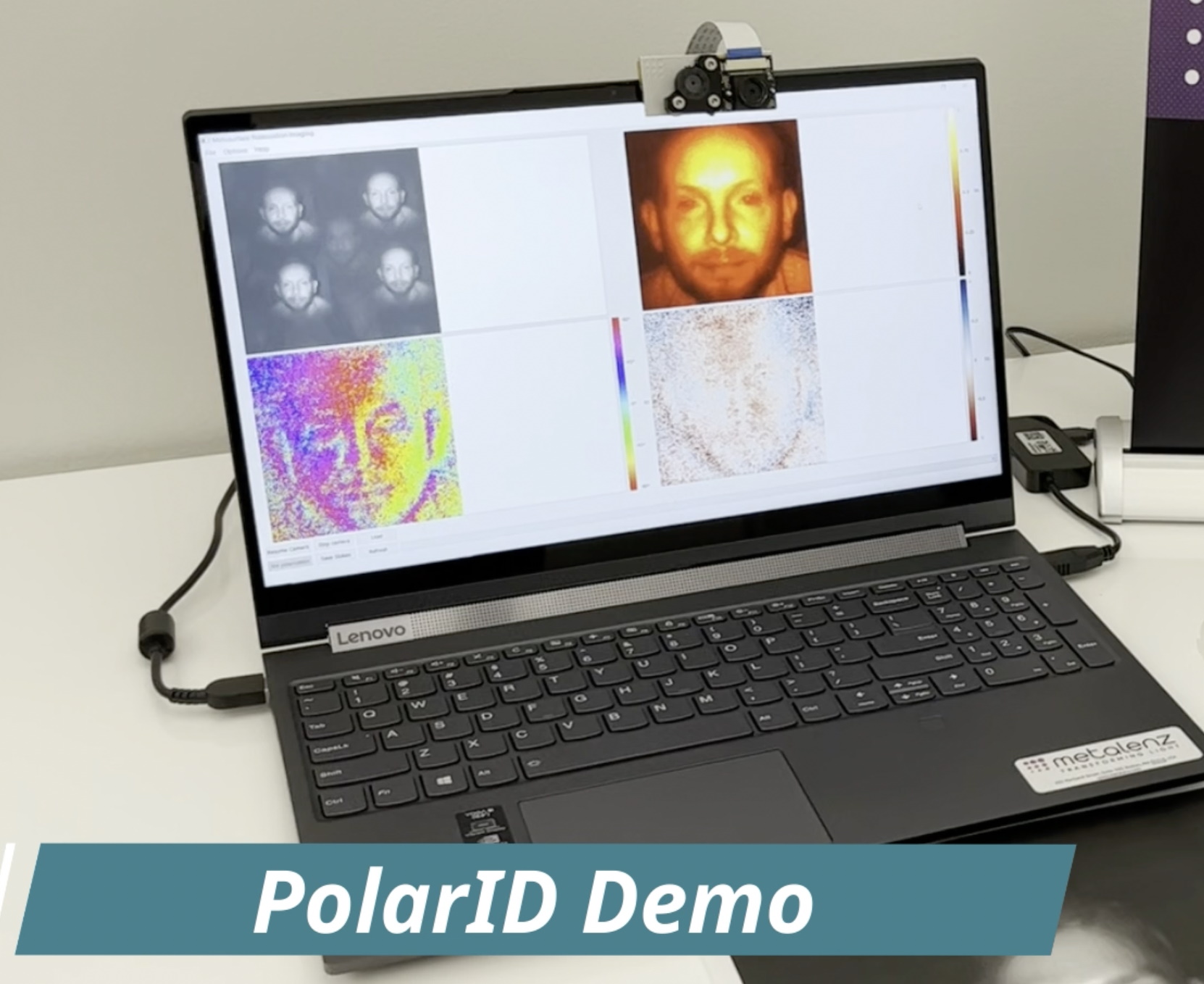

In the case of facial recognition, the unit could be small enough to sit alongside a normal camera in a front-facing array, like the lidar unit in iPhones that currently scans the face using tiny lasers. A polarized light sensor would instead (in this example) split the image into four, presumably corresponding to four different axes of polarization, each of which shows a slightly different version of the image. These differences can be evaluated the way the differences between images taken a small distance or time apart can, allowing the geometry and details of the face to be observed.

Polarized light has the advantage of also being able to tell the difference between materials: skin reflects light differently than a realistic mask or photo. Perhaps this isn’t a common threat in your everyday life, but if a phone manufacturer could get the same “Face ID” type feature, with added anti-spoofing security, and use something less exotic than a tiny lidar unit, they’d probably jump on the opportunity. (And Metalenz is talking to the right people here.)

The automotive and industrial side is also useful, as telling what a given pixel you’re looking at is made of is a surprisingly complex question that usually involves identifying the object it’s part of. But using polarization data you can tell the difference between lots of materials instantly — and in fact this is part of the value proposition of Voyant’s new lidar. You don’t even need a lot of resolution — one polarized pixel for every hundred normal ones would still offer huge insight on a given scene.

All this depends on the ability of Metalenz to make the polarized camera units small and sensitive enough to use in these situations. They’ve reduced the breadbox-scale units used industrially to a cracker-sized one they’ve been testing with, and are working on a Skittle-sized camera stack that could be added or swapped in for other camera units in robots, cars, laptops, perhaps even phones. It’s firmly in the “development” phase of research and development.

Metalenz is currently working off last year’s A round from 3M, Applied Ventures, Intel, TDK and others, the type of crowd you expect to invest in a potentially lucrative new component type. If interest in PolarEyes is anything like what the company had for its first sensor, we can expect another raise to cover the scaling costs soon.