Nothing has been automatic about the success of Automattic.

Today, to those who haven’t been paying attention, the company looks a bit like an overnight success story. WordPress, the open source software behind the company, is now estimated to power roughly 42% of all websites on the internet. Automattic’s e-commerce plugin, WooCommerce, which it purchased in 2015, is believed to run more than a quarter of all online storefronts.

The company has 1,700 employees in a distributed, asynchronous, global workforce, and has raised nearly $1 billion, according to Crunchbase, most recently at a $7.5 billion valuation.

Automattic founder and CEO Matt Mullenweg at TechCrunch Disrupt 2014. Image Credits: TechCrunch

But reaching this point has taken 16 years — or 18, if you count from the founding of WordPress. And over those many years, the company did pretty much everything wrong, if you ask the venture capitalists.

Automattic focused on media at a time when that industry was being demolished by the internet. It eschewed the kinds of walled gardens that turned Facebook, Apple and Google into monopolistic powerhouses and built its business on top of a volunteer-run, open source infrastructure that gave many investors serious pause.

Its workforce has always been fully remote and distributed — 16 years before last year’s pandemic spread that model throughout the corporate world. Automattic’s founder, Matt Mullenweg, was barely of American legal drinking age (21) when he began building, at a time when venture capitalists wanted “adult supervision” at their companies.

But in retrospect, doing everything wrong was exactly the right strategy — a fact that’s just now becoming apparent.

“With exponential growth, things look small until the end,” says Mullenweg. In his reckoning, Automattic isn’t yet close to the end, but the curve is starting to become visible.

It all began with a blog post.

The jazz saxophonist who started a weblog revolution

Massive changes often begin as ephemeral, uncertain ideas. The technology is unstable and experimental; the audience unclear; and the commercial applications murky or completely unknown.

Back in 2003, that was the context for the so-called weblog, which would shortly be elided to blog. Blogger had just sold itself to Google — for an undisclosed and presumably small price. The year before, political bloggers at Instapundit and Talking Points Memo had shaken up American politics when they managed to intensify attention on a story about Trent Lott, forcing his resignation as the minority leader in the U.S. Senate. Yet, traditional media remained the undisputed king of communication, and the era of professional blogs (including the one you’re reading) was still a distant dream.

One early adopter was Matt Mullenweg, a 19-year-old jazz enthusiast in Texas. In a blog post that’s still online, he wrote:

My logging software hasn’t been updated for months, and the main developer has disappeared, and I can only hope that he’s okay.

What to do?

Mullenweg himself didn’t necessarily look like the person to come up with a solution. His interests were eclectic and wide-ranging — while he imagined himself as a future jazz saxophonist, he was also studying political science at the University of Houston, and spent a good deal of his time working on his photography (to this day, Mullenweg’s Twitter handle is @photomatt). His tech hobbies, including open source software, were inspired by his father’s job as a professional programmer, but Mullenweg didn’t yet seem certain about following his father’s profession.

Nevertheless, his post got the attention of a few other developers and the group set out to create the open source WordPress project, focused on blog publishing. The first version of WordPress was released in May 2003 and became the official version of b2, an older project that had been abandoned.

Mullenweg became the center point of a growing community. An October 2004 Houston Press profile of him noted that WordPress was running more than 29,000 blogs. Mullenweg’s own blog was the third most popular in the world, and all the attention he received resulted in an offer to leave college and become a senior product manager at CNET, a San Francisco media company. WordPress, though, was still referred to as a “hobby.”

The good side of spam

CNET turned out to be the perfect employer. The company’s job offer allowed Mullenweg to spend 20% of his time working on WordPress and also let him retain ownership of source code he wrote while at the company. The role also gave him an inside view of the internal systems of a large media organization.

One of the things he saw would turn out to be a major problem across the internet: spam. CNET’s sites that allowed comments were inundated. Battling the bots gave Mullenweg an idea for a commercial product. Akismet, a spam filter, wasn’t just for WordPress; it worked with most popular blogging software. When Mullenweg left CNET less than a year later to found Automattic (inscribing his name in the company’s with an extra “t”) and sell Akismet, his first hires were WordPress contributors.

“We’d already been working together for a year or two at that point. It was an experiment to see if we could support ourselves during the day,” says Mullenweg.

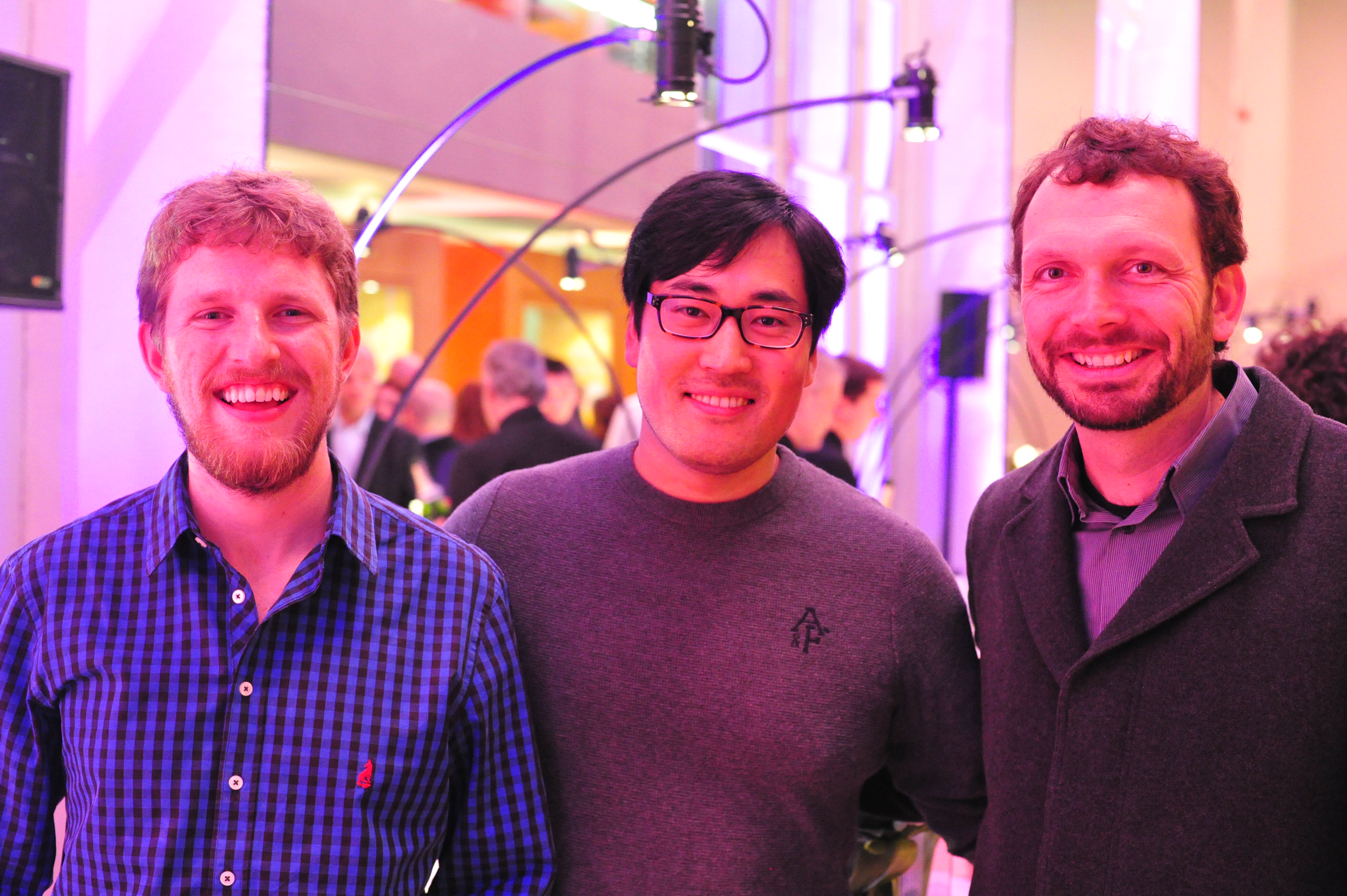

Automattic founder Matt Mullenweg (left) in 2006. Also pictured are Tom Conrad, former CTO of Pandora (center), and Scott Beale, founder of Laughing Squid (right). Image Credits: Matt Mullenweg

Akismet established a freemium model that remains essentially the same today: Free for personal users with a small number of comments, and paid for enterprise users with unlimited needs.

A few months later, Automattic launched WordPress.com to a limited audience. It offered fully managed WordPress hosting, allowing customers to focus on their content rather than managing their web servers. To become an early user, the company auctioned a set number of “golden tickets,” a wink to “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.” Mullenweg recalls, “The tickets were selling for $80 on eBay, so that told us something about the pricing.”

Even when the tickets sold out, the company still didn’t anticipate a moonshot future.

“If I’m really honest, at the very beginning I thought a great outcome would have been selling to Yahoo or Google for probably $20 million to $30 million,” he said.

Testing the boundaries of entrepreneurship

Mullenweg quickly decided that Automattic had more potential than he’d initially thought. But to many outside observers, the company looked unlikely to succeed. Automattic was taking shape around two untested ideas, each of which gave potential partners and funders pause.

First, Automattic was building a commercial counterpart to an open source project. While that model has proven wildly profitable, back in the early 2000s, there were few role models to follow. Worse, open source itself didn’t have the greatest reputation, either.

“One assumption of open source at the time was that it couldn’t innovate. Proprietary would innovate and open source would copy,” recalls Mullenweg. Partly due to investor reluctance, companies based on open source codebases remained either small or ended up subsuming the project that had given birth to them.

Second, Automattic’s employees were spread around the world and worked asynchronously, since much of WordPress was developed by volunteers coordinated over the internet. At the time, Silicon Valley’s idea of cutting edge was bringing down cubicle walls and having employees work side by side in open offices; Automattic’s work style simply looked bizarre.

The final challenge was two-fold: Mullenweg was only 21, with no prior successes under his belt, and youthful founder CEOs weren’t yet in vogue with venture capitalists (Mark Zuckerberg, who perhaps more than any entrepreneur changed this perception, had only started Facebook the year before).

“I’d met my business soulmate”

Michael Arrington, founder, TechCrunch (left), and Om Malik, partner, True Ventures (right), attend the TechCrunch 9th Annual Crunchies Awards at War Memorial Opera House on February 8, 2016 in San Francisco, California. Image Credits: Steve Jennings/Getty Images

Around the time Mullenweg was starting Automattic, Om Malik, a journalist and blogger, introduced him to Toni Schneider, a Yahoo executive who’d landed at the tech giant through an acquisition.

Schneider was immediately impressed by Mullenweg. “He listens more than he talks, but when he talks he’s incredibly sharp, with a long-term vision,” says Schneider. “He was 21 and he said he wanted to work on WordPress for the rest of his career. In Silicon Valley, you’re constantly surrounded by people jumping from one thing to the next every year.”

Mullenweg’s persona tends to shine through when talking to anyone who knew him at the time. Continuing in his description, Schneider used the word “calm” three times — and indeed, the same word pops up regularly in relation to him.

Today, of course, the prospect of a 21-year-old founder with a calm, stable persona and good listening skills would likely be aggressively pursued by venture capitalists, who would also be extremely unwilling to let such a founder step aside for a more experienced CEO.

But it shouldn’t be said that Mullenweg wasn’t unwilling to give up his position. For his part, he says, he instantly knew Schneider could teach him to someday lead a large organization.

“I’d met my business soulmate,” he says.

Six months after Automattic was founded, Schneider was hired as CEO, a position he would hold from 2006 to 2014.

Ignoring the ad economy

Automattic co-founder Matt Mullenweg (left) with then-CEO Toni Schneider (right) in 2010. Also pictured is Chang Kim (center), who was a product manager at Blogger.com and is now CEO of Tapas Media. Image Credits: Matt Mullenweg

Mullenweg was able to secure both Schneider and an initial seed investment from Polaris and True Ventures (which Schneider would later join as a partner, a title he retains to this day), but Automattic still needed to find its place in the world. Initially, the startup focused on turning WordPress into the leading blogging platform.

“We were late; there were others ahead of us,” says Schneider, naming Blogger and Six Apart, which published the Movable Type blog platform, as examples of the hot names of the day. “We had ground to make up, and it wasn’t clear early on that blogging would be a big business,” says Schneider.

As it turned out, blogging wasn’t a huge business — at least not in the way that WordPress’ rivals wanted it to be. After acquiring Applied Semantics in 2003 and DoubleClick in 2007, Google was raking in advertising revenue through its search and display advertising businesses. Its ownership of Blogger led most of the industry to conclude that they needed to compete by monetizing blogs with ads.

In retrospect, advertising was the wrong direction for the ecosystem. It was a business model that would only work years later, in the more constrained, predictable environment of social platforms like Facebook and Instagram. These platforms would provide uniform content types and large quantities of users, and precise targeting and analytics could combine to make advertising effective and profitable.

Automattic didn’t follow the zeitgeist. “When we asked our users, ‘Who wants ads?’, 20% said that’s great, [but] the others didn’t want ads,” says Schneider. WordPress was, after all, a community-driven project, so the community’s voice won out.

Without advertising, the company began looking for other sources of subscription revenue beyond its original offerings of Akismet and WordPress.com. “Automattic as a business didn’t begin to take off until we went beyond blogging to small business websites and enterprise hosting with [WordPress] VIP. Those are stronger businesses than personal blogging,” Schneider said.

This was likely the point that Automattic became, to outside observers, a somewhat confusing company. Each new product had its own business model and subset of customers and its acquisitions of blog-commenting software IntenseDebate in 2008 and survey product PollDaddy added even more facets to the business.

Each new business added revenues and buttressed the wider WordPress ecosystem but made it harder to understand exactly what Automattic was or what it was trying to become.

Let everyone else get distracted

By the time the 2010s rolled around, attention had mostly shifted away from companies like Automattic. Facebook, and later Twitter, were convincing many media followers that walled gardens were the future.

Automattic did almost nothing to follow the new trends.

“Matt’s leadership is slow and cautious. We definitely had pressure to try and build some of those things,” says Schneider. “A lot of founders and entrepreneurs I work with — and I’d put myself in this — are the type of personality that likes the shiny new thing. Matt’s not like that. His attitude was, ‘This is great, everyone will get distracted and sooner or later we’ll be the last one standing.’”

There was good reason for Automattic to stand its ground: The open web continued to grow. Mullenweg points out that even though social was growing, all the links posted on social networks lead back to websites — many of which were published with WordPress.

Schneider recalls one point at which he worried that the company might lose out.

Backstage at Disrupt SF with Jack Dorsey, co-founder of Twitter, with former TechCrunch reporter Colleen Taylor. Image Credits: TechCrunch

“With Facebook, it wasn’t like people abandoned their WordPress site. [But] with Twitter, there was a lot of overlap. The comments and interactions moved from the comment section of blogs over to Twitter, because it was just a quicker, better, more fun way to have a conversation. We tried all these things to shore it up and make it better, but at some point we realized, that’s okay,” says Schneider. “I think what we realized was that there’s always going to be a huge need for people to own their own web presence.”

The VIP (business) line

As the rush to social platforms went on, a new trend came to light: Large companies were finding and using WordPress without ever hearing from Automattic.

“We had to show people, like Time Magazine or sites for CBS Local, that you could use WordPress as a full-featured content management system,” says Paul Maiorana, who was working in enterprise sales for Automattic (he’s now CEO of the WooCommerce subsidiary). “The perception lingered that it was just a blogging system.”

WordPress VIP CEO Nick Gernert was working at Voce Communications (a part of Omnicom, one of the largest marketing and design agencies) before joining Automattic in 2013. He recalls, “The amount of WordPress that was being deployed by companies within Omnicom was significant — Merck, Capital One and similar. But there was no connection to Automattic.”

Many of these companies were beginning to migrate away from the proprietary software they’d used to manage their web presence earlier in the 2000s. “We did the numbers, and it was something like 26% of the Fortune 100 had WordPress somewhere in the organization,” says Gernert, although WordPress was usually a secondary or tertiary solution. Automattic decided it could claim more of that business.

Almost since WordPress.com was launched in 2006, Automattic had offered a “VIP” pricing level that had greater support, security and technical guarantees than the basic paid tier. As demand increased from larger publishers, WordPress VIP became a full-fledged and independent business line: A fully managed service that helped large companies with their hosting, source control, development environment and combing through the confusing mass of thousands of plugins and themes available in the ecosystem. (It’s probably useful to note that TechCrunch is run on WordPress VIP).

In addition, the company launched Jetpack in March 2011, which brought some of the cloud-native features of WordPress.com to self-hosted WordPress.org installations. Or as Mullenweg described it in a blog post at the time:

Now you can have your cake and eat it too — host your own blog, completely under your control and with the freedom of the GPL [the open source GNU General Public License], and still get all the cloud goodies of our hosted service. It’s the best of both worlds, the decentralized and the centralized, the control and the convenience, the peanut butter and the chocolate.

It was around this point that Automattic began letting some of its divisions operate more independently. VIP had been the first to build its own leadership structure, and Jetpack, which had been intentionally given a separate identity, organically followed the same path. Still, it would take until 2018 before Automattic named the first CEO of a subsidiary (again choosing VIP as the first).

New competition arrives

Squarespace CEO and founder Anthony Casalena (right) in an interview with former TechCrunch editor John Biggs in 2012. Image Credits: TechCrunch

Most of the tech world had moved on to social networks, but Automattic did face a handful of serious direct competitors. Among these were drag-and-drop site builders like Squarespace, Wix and Weebly, which had been founded contemporaneously with Automattic and had grown to millions of paying subscribers by the early 2010s.

These companies had several advantages over WordPress.com. Their software was proprietary and focused on narrower use cases, which allowed for an easier, more intuitive experience for new users. Vitally, since every customer paid a hefty monthly fee, the site builders were able to enormously spend on marketing.

Automattic, for its part, had no marketing department, spent nothing on advertising, and happily informed users of multiple options to use WordPress for free. By the mid-2010s, heavy advertising from Squarespace and Wix had made those brands feel ubiquitous, even though WordPress was powering many more websites.

But the competition had one weakness: They had to stay focused on narrow, highly profitable niches, such as small business websites. Both Automattic and the WordPress community, by contrast, wanted their software to solve any use case that could be dreamed up, and they had the developers to do it.

“We had many more places to go to expand the business, and I think that’s what we’re seeing today. Automattic is growing in all different directions simultaneously, while Wix and Squarespace are beating each other up,” says Schneider. “The businesses that are more focused on selling one type of thing might scale more quickly, but if a new type of commerce comes along, they have a really tough time.”

“What we chose, and what we choose today, is to focus on usage and market share and community over the short-term optimization of revenue optimization or thinking quarter to quarter,” says Mullenweg.

The Automattic flywheel

The mid-2010s brought some of the most significant events in the company’s history. First, in January 2014, Automattic raised a huge $160 million venture round led by Insight — the only money it had taken since 2008.

Mullenweg, in an interview with TechCrunch at the time, explained that he realized the company had become “capital constrained,” having only raised $12 million previously. Later that year, Mullenweg replaced Schneider as CEO, coming back as head of the company. Schneider, who had been moonlighting as a venture capitalist with True Ventures, began working at the firm full time.

Mullenweg plotted to expand the range of Automattic’s offerings. Most notably, in 2015, Automattic acquired WooCommerce, an e-commerce plugin for WordPress that had gained widespread attention in the ecosystem. The acquisition went largely unnoticed.

Just as Facebook and Twitter had sucked up the oxygen in the room while Automattic was growing beyond blogs, Amazon was taking most of the attention in shopping. WooCommerce would quickly turn into a giant within Automattic, claiming a larger share of all e-commerce sites than the much better-known Shopify (see part three of this TC-1 for more on WooCommerce).

Acquisitions like WooCommerce revealed a new trend: The WordPress open source ecosystem was producing innovative startups that had modeled themselves off Automattic and usually had extensive interactions with the company. When Automattic wanted to acquire a startup from the ecosystem, it was often easy to slot into the company’s roadmap.

“The cool thing about our M&A is our pipeline. It’s different. We look at WordPress innovation out in the world and say, ‘That company would be awesome, it fits with our business model, and if we bought them, we’d have little to no integration risk,’” said Mark Davies, who joined Automattic as chief financial officer in 2019. Plus, “there’s no business risk, because we know what we’d do if we bolted it into the Automattic flywheel.”

WordPress for (almost) everything

WordPress branding. Image Credits: WordPress.org

WooCommerce wasn’t the only big addition to Automattic’s product lineup. Within the WordPress project, work was underway to modernize the platform’s codebase and content management system (CMS), including the multiyear effort to build a new system called Gutenberg (which we will explore more in part two of this TC-1).

The work was messy and, as usual for open source projects, not popular with everyone, but Mullenweg’s evangelization of the updates carried along enough of the community. The number of use cases for WordPress continued to grow, and with it, the proportion of the internet using it. In 2013, WordPress was reportedly powering 20% of the top 10 million sites. That number hit 25% in 2015 and 30% in 2018.

Another driving force was the fragmentation of software used by larger organizations. For years, most companies had built their entire web presence on a single tech stack, such as Adobe’s website and design tools. But as the web became more complex, large organizations began piecing together different technologies, offering Automattic an opening.

“The old paradigm was, I got my one license, they were OK and at least I’ve got it all. We’re looking at it now and thinking: ‘It’s a much more integrated future,’” says Gernert, WordPress VIP’s CEO. Today, companies like Facebook, Salesforce and Credit Karma now use WordPress for parts of their web presence.

Acceleration after “steady, steady, steady”

The spotlight has at last begun to swing back toward Automattic over the past few years.

Walled gardens, previously the darlings of tech investors, are facing headwinds. Social networks, from Facebook to TikTok, still attract massive user numbers, but their reputations have declined sharply.

Similarly, in the e-commerce world, Amazon has passed its peak popularity among merchants due to its authoritarian store policies and reports that it is using its own platform data to copy their products.

“There’s a huge amount of criticism and pushback to these big centralized players, because of the privacy violations that have risen to the forefront, because of all the ad tracking, because [of] all the awful things that happen on these networks at scale,” says Schneider. “We’ve been saying this all along: You want to have an open, distributed platform, not just for the heck of it. And that’s playing out now.”

And as the internet evolved, Salesforce saw promise in Automattic. In 2019, Salesforce invested $300 million for a 10% stake in the company.

By the standards of the internet giants, Automattic has always grown at a slow and steady clip, but the company has now started to expand at a faster pace. “Our margin is accelerating massively: It’s 600 basis points of gross margin in two years. Our growth rate is accelerating — we’re actually growing faster as we’re bigger, which kind of shows the scale,” says Davies.

Schneider says that the Salesforce investment, along with the increasing separation of Automattic’s businesses into separate operating units like WordPress.com, WordPress VIP, Jetpack and WooCommerce, helped drive the company’s acceleration. Later, COVID-19 also pushed the company’s growth as more of the world moved online.

“Before, it was steady, steady, steady. Now, these factors have really put it into a different gear,” he said. “But it’s not a surprise to anyone around the table. It’s not, ‘Oh my god, we’ve found this new product … ’ When I look at the company today, it’s much bigger, but it’s not that different. We haven’t pivoted, we haven’t changed anything. We’ve stuck to our guns, stuck to the open-web approach.”

Mullenweg and Automattic never followed the rules or the reigning paradigms in tech. Yet, Automattic has cash, a growing user base, an expanding product lineup, and we haven’t even covered its acquisition of Tumblr, Parse.ly and a myriad of other businesses. It’s the media conglomerate that few have heard of even as they regularly land on sites powered by WordPress.

For all those diverse products, however, Automattic’s relationship with the open source WordPress project remains critical for its long-term success — the subject of part two of this TC-1.

Automattic TC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Open source development

- Part 3: Acquisitions and future strategy

- Part 4: Remote work culture

Also check out other TC-1s on TechCrunch+.