It’s a story common to all sectors today: Investors only want to see “uppy-righty” charts in a pitch. However, edtech growth in the past 18 months has ramped up to such an extent that companies need to be presenting 3x+ growth in annual revenue to even get noticed by their favored funds.

Some companies are able to blast this out of the park — like GoStudent, Ornikar and YouSchool — but others, arguably less suited to the conditions presented by the pandemic, have found it more difficult to present this kind of growth.

One of the most common themes Brighteye sees in young companies is an emphasis on international expansion for growth. To get some additional insight into this trend, we surveyed edtech firms on their expansion plans, priorities and pitfalls. We received 57 responses and supplemented it with interviews of leading companies and investors. Europe is home to 49 of the surveyed companies, with six firms based in the U.S., and three in Asia.

Going international later in the journey or when more funding is available, possibly due to a VC round, seems to make facets of expansion more feasible. Higher budgets also enable entry to several markets nearly simultaneously.

The survey received responses from a roughly even split of target customers across companies, institutions and consumers, as well as a good spread of home markets. The largest contingents were from the U.K. and France, with 13 and nine respondents respectively, followed by the U.S. with seven, Norway with five, and Spain, Finland and Switzerland with four each. About 40% of these firms were yet to foray beyond their home country and the rest had gone international.

International expansion is an interesting and nuanced part of the growth path of an edtech firm. Unlike their neighbors in fintech, it’s assumed that edtech companies need to expand to a number of big markets in order to reach a scale that makes them attractive to VCs. This is less true than it was in early 2020, as digital education and work is now so commonplace that it’s possible to build a billion-dollar edtech in a single, larger European market.

But naturally, nearly every ambitious edtech founder realizes they need to expand overseas to grow at a pace that is attractive to investors. They have good reason to believe that, too: The complexities of selling to schools and universities, for example, are widely documented, so it might seem logical to take your chances and build market share internationally. It follows that some view expansion as a way of diversifying risk — e.g., we are growing nicely in market X, but what if the opportunity in Y is larger and our business begins to decline for some reason in market X?

International expansion sounds good, but what does it mean? We asked a number of organizations this question as part of the survey analysis. The responses were quite broad, and their breadth to an extent reflected their target customer groups and how those customers are reached. If the product is web-based and accessible anywhere, then it’s relatively easy for a company with a good product to reach customers in a large number of markets (50+). The firm can then build teams and wider infrastructure around that traction.

But if the product requires selling to businesses, then the expansion process is more hypothesis-driven and therefore self-starting and more hands-on. Here, expansion tends to be defined by a set number of sales or local partners within a market — for example, selling to more than five universities.

How “entering a market” is defined will shape a company’s approach to building a team for the market. Companies need to decide both where and how to expand. For instance, do they need to hire an execution specialist or a head of sales? The answer will depend on how much the product will need to be tweaked versus how directly transferable the product is to the new market. If it is directly transferable, a sales lead might be more logical than a general manager, for instance.

This might also be more preferable if the immediate priority is scaling revenue and building brand awareness in the new market. But how easily you can do this with a small sales team will depend on how difficult it is to service the customers in home markets via incumbent marketing, customer success and other teams.

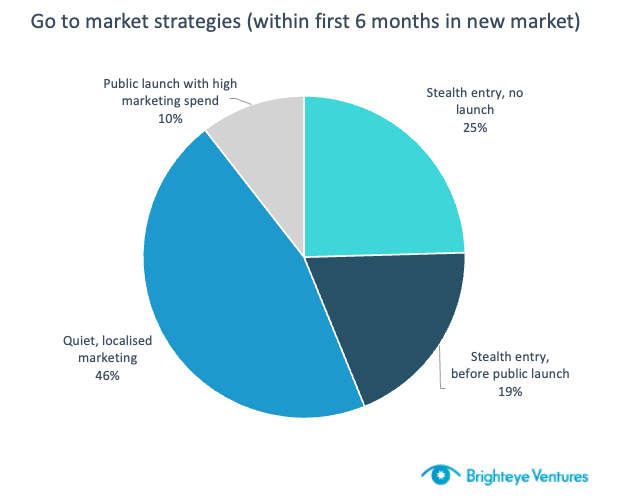

Variation in how you set up an expanding team and enter the market(s) will depend largely on the budget you have available — VC funding aside, this depends on your annual revenue in your home market. This partially explains why many companies pursue a regional approach to expansion, particularly in large markets. The new region acts as a testing ground for your market-fit hypotheses and can be used as a launchpad to expand to other parts of the market. This kind of entry is quite preferred — 71% of respondents opted for a quiet entry without a public launch.

Image Credits: Brighteye Ventures

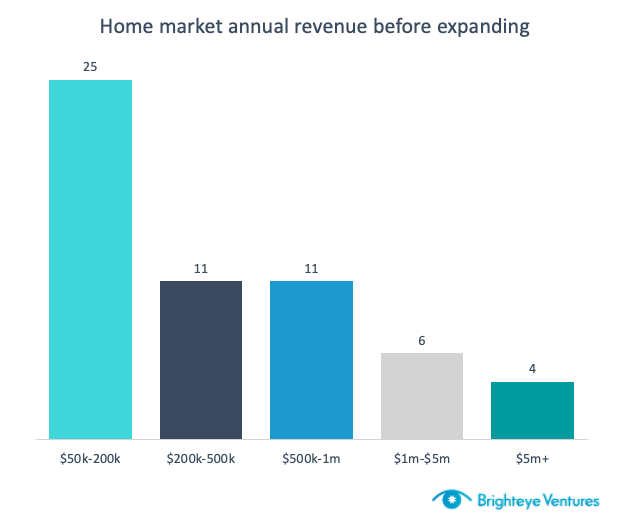

Expansion is front of mind for many thriving early-stage firms. About 82% of the respondents said they expand with annual revenues under $1 million, while 44% expand when revenues are between $50,000-$200,000. It’s important to note that some European markets’ total populations are equal to that of large cities, so expansion is a very necessary part of growth for these firms. This also makes it less surprising that companies with lower revenues plan to expand early.

Image Credits: Brighteye Ventures

A fully planned expansion roadmap doesn’t seem to be a prerequisite, though. Strong traction in the home market seems more important. Amit Patel, a managing director at Owl Ventures, said companies must have strong, predictable local performance prior to expanding, given the additional stresses that expansion places on companies. You wouldn’t (shouldn’t, at least) build a house without foundations.

Expanding early without a coherent justification for entry is a risky approach that can make it harder to find appropriate early hires that fit what’s needed. You can also risk rushing user testing and associated product tweaking, leaving you with less time to consider and allocate expansion budgets, and consequently losing the best aspects of your home market culture. These are four of the biggest challenges facing expanding companies.

The best way to de-risk the process is to form and pursue a coherent framework via which to consider your expansion options. This will require taking the time to understand how and why you achieve market-fit in your home market.

The logical first step is to define practical constraints and parameters like time zones and language requirements, develop a defendable hypothesis on your market fit, seek and compare markets on how well they fit your approach, and finally, undertake user testing.

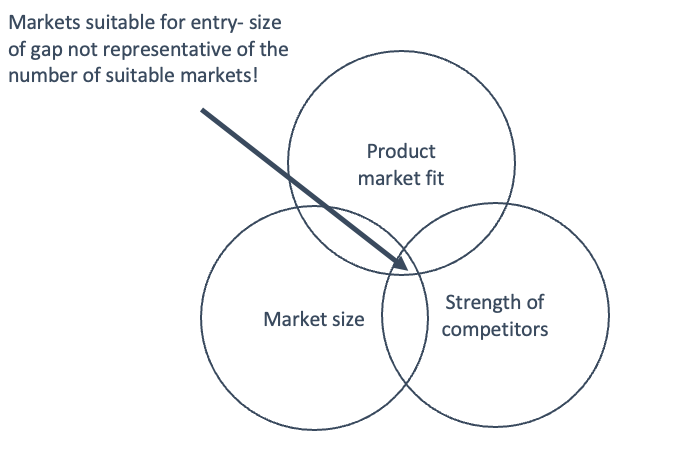

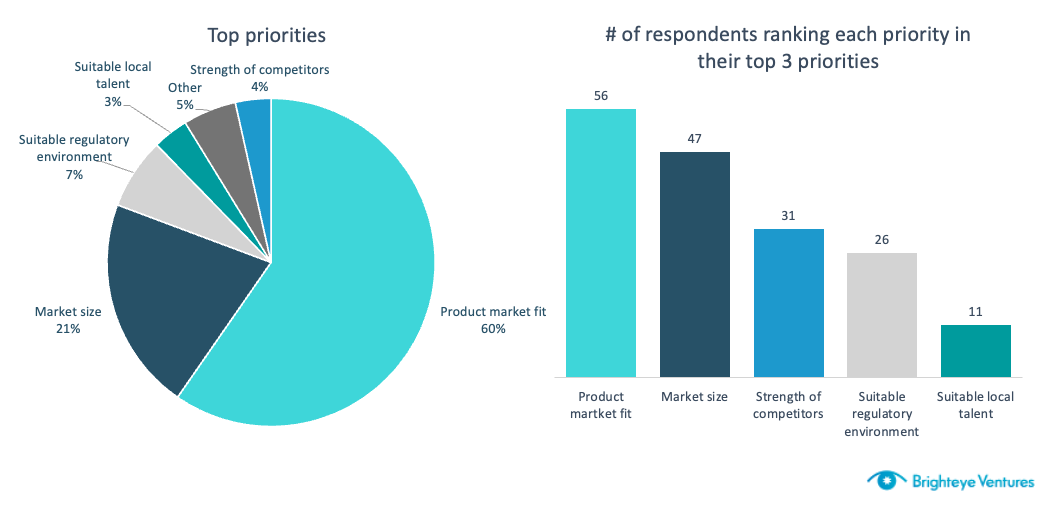

The survey data indicates that companies look to expand to markets that sit in the middle of a Venn diagram with market size, product-market fit and strength of competitors as the overlapping circles.

Image Credits: Brighteye Ventures

Early-stage businesses are likely to expand to a neighboring market, given lower budgets and a desire to maintain relatively centralized operations. The survey evidence supports this proposition: 50% of European edtech startups expand to another European market. They prefer this route because of similar customer profiles, wealth, willingness to pay for education, regulatory environments and practical reasons like time zones.

Image Credits: Brighteye Ventures

The most popular markets for first-time expansions in Europe are the U.K., Spain and Sweden, which can all be considered “gateway” markets that unlock further expansion paths. The U.K., for instance, unlocks the U.S. and some Northern European markets; Spain unlocks Southern Europe and LatAm; and Sweden is often considered a pathway for Nordic companies seeking to enter larger European markets.

Going international later in the journey or when more funding is available, possibly due to a VC round, seems to make facets of expansion more feasible. Higher budgets also enable entry to several markets nearly simultaneously — respondents based in northern Europe expanded to 1.9 new markets during their first expansion. An increasingly popular option is to expand to one neighboring, similar market (a safe expansion), and one larger, more complex market (a riskier expansion).

The survey data shows that international expansion remains of central importance to ambitious edtech firms. But companies need to make sure the decision and process are strategic, coherent and structured. The grass may seem greener on the other side, but you could also find yourself staring at weeds.

You can download the survey analysis here, including the Annex splitting the data by whether companies had internationalized or not and by target customer groups (companies, institutions and consumers).