There’s an old startup adage that goes: Cash is king. I’m not sure that is true anymore.

In today’s cash rich environment, options are more valuable than cash. Founders have many guides on how to raise money, but not enough has been written about how to protect your startup’s option pool. As a founder, recruiting talent is the most important factor for success. In turn, managing your option pool may be the most effective action you can take to ensure you can recruit and retain talent.

That said, managing your option pool is no easy task. However, with some foresight and planning, it’s possible to take advantage of certain tools at your disposal and avoid common pitfalls.

In this piece, I’ll cover:

- The mechanics of the option pool over multiple funding rounds.

- Common pitfalls that trip up founders along the way.

- What you can do to protect your option pool or to correct course if you made mistakes early on.

A minicase study on option pool mechanics

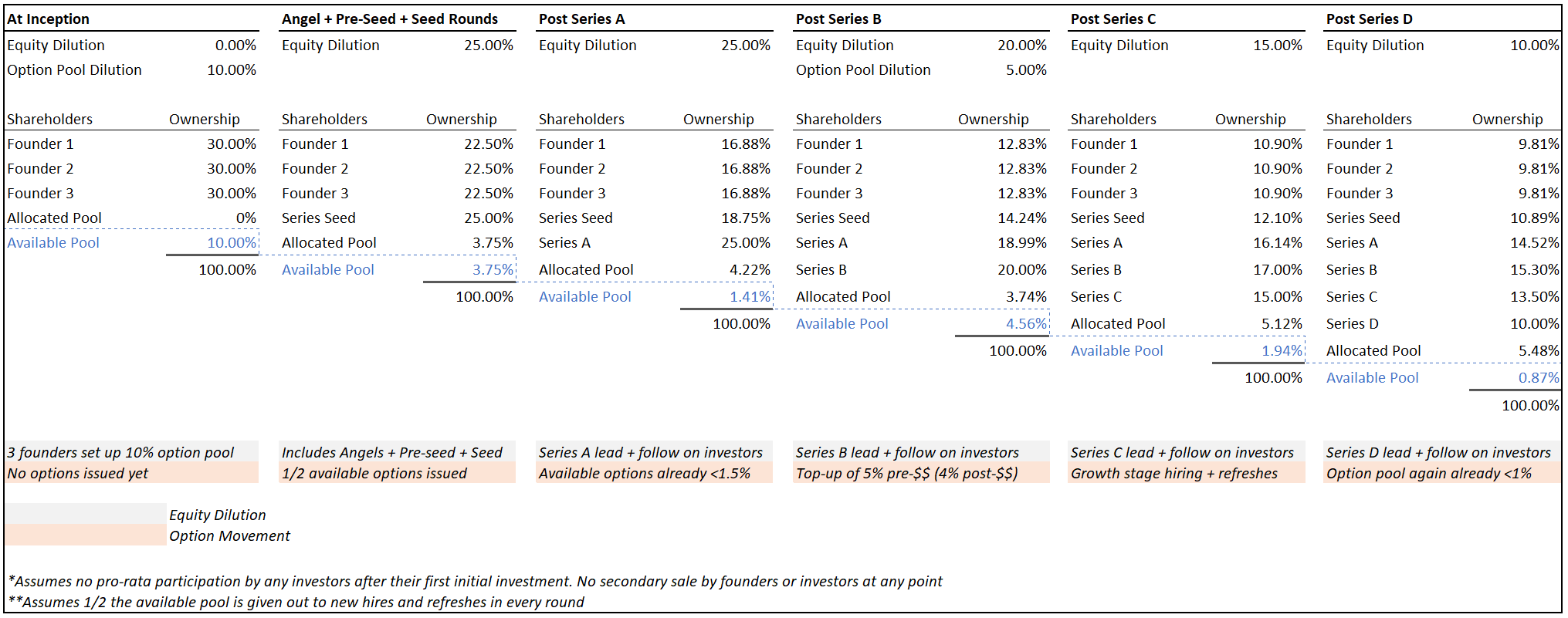

Let’s run through a quick case study that sets the stage before we dive deeper. In this example, there are three equal co-founders who decide to quit their jobs to become startup founders.

Since they know they need to hire talent, the trio gets going with a 10% option pool at inception. They then cobble together enough money across angel, pre-seed and seed rounds (with 25% cumulative dilution across those rounds) to achieve product-market fit (PMF). With PMF in the bag, they raise a Series A, which results in a further 25% dilution.

The easiest way to ensure you don’t run out of options too quickly is simply to start with a bigger pool.

After hiring a few C-suite executives, they are now running low on options. So at the Series B, the company does a 5% option pool top-up pre-money — in addition to giving up 20% in equity related to the new cash injection. When the Series C and D rounds come by with dilutions of 15% and 10%, the company has hit its stride and has an imminent IPO in the works. Success!

For simplicity, I will assume a few things that don’t normally happen but will make illustrating the math here a bit easier:

- No investor participates in their pro-rata after their initial investment.

- Half the available pool is issued to new hires and/or used for refreshes every round.

Obviously, every situation is unique and your mileage may vary. But this is a close enough proxy to what happens to a lot of startups in practice. Here is what the available option pool will look like over time across rounds:

Image Credits: Allen MillerNote how quickly the pool thins out — especially early on. In the beginning, 10% sounds like a lot, but it’s hard to make the first few hires when you have nothing to show the world and no cash to pay salaries. In addition, early rounds don’t just dilute your equity as a founder, they dilute everyone’s — including your option pool (both allocated and unallocated). By the time the company raises its Series B, the available pool is already less than 1.5%.

While the option pool top-up (5% in this example) at the Series B helps to grow the unallocated pool, it is typically done so on a pre-money basis, meaning the new equity coming in as part of the round immediately dilutes the top-up. So, the resulting increase to the pool is closer to 4 percentage points than 5. The real dilution to everyone else on the cap table (founders, employees and investors) ends up being closer to 25% versus the 20% it would be if this was only an equity round with no top-up.

The company is again at less than 1% in available options at the Series D (two rounds after the top-up). This means further top-ups may be required, albeit at smaller amounts. The good news is that by the time of Series C and D rounds, 1% of equity can afford many more multiples of employees than 1% at the seed or Series A. Larger growth rounds also mean that cash compensation can become much more competitive, making up for smaller equity packages.

Common pitfalls

As you can see, even in this relatively “clean” scenario where the founders had the foresight to open with a 10% option pool, raised good up rounds (with stage appropriate dilution) and only had one top-up round along the way, they were likely still managing/hiring on close to a shoestring budget. This is not a position you want to be in, especially in today’s competitive talent market.

The reality is that things can get much messier, leading to a thinner option pool earlier on that can impair your ability to hire great people. Here are a few common traps that can pop up and wreak havoc on your option pool:

Poor planning: You simply don’t have a sizable option pool right from the outset. You underestimate hiring needs or are overly sensitive about ownership. Many first-time founders make this mistake.

Co-founder departures: Your co-founder, who has material ownership, leaves after a year or two. While they only vested a quarter or half of their shares, that can be 5%-10% of dead weight on the cap table doing little for the company.

Giving out too much to early hires: You give out too much equity to early employees who are unqualified for their role or demand too much equity even after adjusting for stage risk. They then have to be replaced a few years in with a more seasoned hire, which makes you “double pay” in equity for that role.

Hiring execs at the wrong time: A derivative of the above is hiring senior leaders too early. For example, hiring an expensive CRO at the Series A stage, when you would be better off doing founder-led sales or hiring a few AEs. The CRO hire will be more impactful to the company by the time of the Series C and likely less costly on the equity front.

Not firing quickly enough: Failing to use the one-year cliff as a forcing function to make decisions on performance. If you let poor performers linger too long, you will almost always regret the equity that could have been used for an awesome hire. This needs to be balanced carefully with maintaining a healthy work environment and positive hiring dynamic.

Not using data/benchmarks: Making an equity offer on a whim/using your gut almost always ends badly. Either you end up overpaying and giving out too much equity, or you give out too little and turn away good candidates. Using benchmarks also makes negotiating offers with candidates easier, as it lends the perception of a competitive and fair offer.

OK, you made a mistake, but there’s still hope

If you have hit the growth/later stages and made mistakes similar to those above, you still have a few ways to correct course:

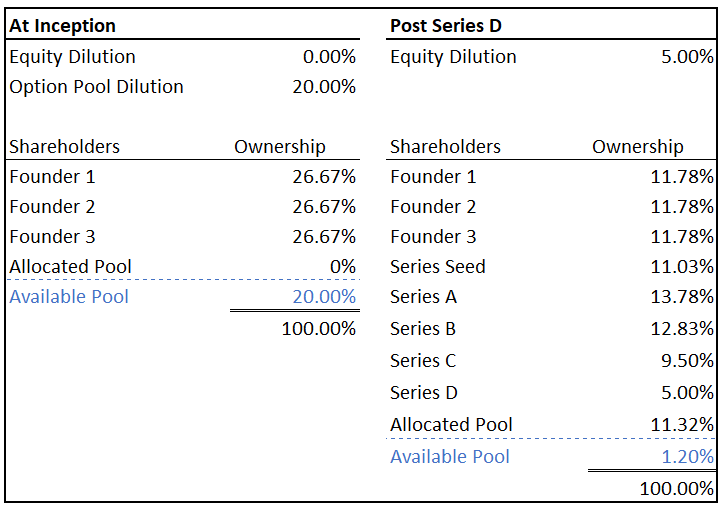

Create a bigger pool earlier on: The easiest way to ensure you don’t run out of options too quickly is simply to start with a bigger pool. As a founder, you might worry about more dilution from a bigger initial pool, and while that may be true in the short run, the flip side is that, with more options, you can hire faster and get better quality talent. That should translate to more progress, allowing you to raise competitive rounds with less dilution over time.

To use the example above: If you were to start with a 20% option pool instead of 10%, but then reduce dilution at each round by 5 percentage points, by the Series D you’d end up with higher ownership as a founder, more (and better incentivized) employees, and less heartache around pool management. Here’s a view of the end state by Series D in this scenario:

Image Credits: Allen Miller

Hire slow, fire fast: Take the time to make sure you want to hire any individual. Especially early on or for senior roles, which tend to be the most expensive. And if it’s clearly not working, end the relationship as quickly as possible and certainly well before vesting starts to happen. This applies to co-founders, too.

Consider longer vest periods for founders/early employees: The co-founder departure scenario is a tough one, as founder equity tends to be significant and can result in lots of dead equity on the cap table. Consider lengthening vest periods to something beyond the standard four years, or make the vesting more back-ended — Amazon-style. If a departing co-founder has already vested equity, consider buying out their shares at a discount and put those shares back in the pool.

Hold budget/planning sessions on employee compensation each year: Forecasting key hires one or two years ahead can do wonders to help you think about the pace of option grant issuance and the trade-offs you have to make for each role/hire. At some point, usually in the midgrowth stages, it’s a good idea to establish a compensation committee, usually chaired by an independent board member, to review compensation each year and recommend decisions to the broader board.

Use benchmarking (and other) data tools to make offers: Startup compensation tools like Option Impact, Carta Total Comp and Pave are must-haves as you scale your company. They will make sure your offers are grounded in solid comps by stage, geography and title. More often than not, founders end up being too generous on the equity side. Using a compensation tool helps ground offers in data and prevents too much equity being granted too early on. You can also triangulate these benchmark tools with feedback from other founders and existing investors.

Tie refreshes and earn-outs closer to performance: As your company scales, consider tying refreshes and earn-outs closer to performance. This is particularly applicable for sales front, but can be useful even for marketing, product and GM-style roles that impact the acceleration of top-line growth. If performance leads to accelerated growth, everyone wins and such performance warrants additional equity.

Skew comp more toward cash in the later stages: As your company scales into the later stages, the risk decreases, and you have more cash to pay employees jumping on your rocket ship. 1% of equity in the later stages can be used to hire hundreds of employees; especially when you have the cash from growth rounds to pay higher bases + bonuses.

Utilize buybacks as a non-dilutive way to grow the pool: Buybacks can be used with angels, early investors and even employees, all of which may have made a nice return by the time of the Series C/D round, and may be willing to partially or fully exit, allowing you to use cash on the balance sheet to repurchase shares and put them back into the option pool.

One important concept to remember is the value of fundraising at milestones where you can minimize dilution. In the example above, we started with the notion that founders can manage to keep dilution to 25% before the Series A. However, this number often ends up closer to 30%-40% before the first major institutional round.

Future fundraises and option pool top-ups then end up diluting more, which can catch founders by surprise. Focusing on achieving clear milestones before raising capital prevents premature and heavily dilutive rounds.

Managing your option pool is key to the long-term success of your startup. In many ways, your option pool is the most important currency you have as a founder. With careful planning and some thought, you can turn your option pool into a powerful driver of growth and enterprise value.