In early 2021, a Nuro autonomous delivery vehicle pulled to a halt at a four-way stop in its hometown of Mountain View, California to let a user cross. This seemingly humdrum moment quickly looked like a decidedly science fiction storyline — the user was a small sidewalk robot from another startup on its own mission.

“Obviously, we yielded to it, but it was, wow, we have entered a different world,” said Amy Jones Satrom, head of Operations at Nuro.

Mountain View is home to competitor Waymo and other autonomous vehicle testing activity. But for those who want to take part in that science fiction scene, Houston provides the full experience.

Nuro’s operations team has to delicately balance speed, safety, convenience and congestion, even as the company embarks on a growth spurt that will see robots spreading to other cities, states and partners in the months ahead.

Waymo is testing self-driving trucks in Houston, and a fully driverless shuttle service is due to start public service there early next year. Nuro’s Texas effort started in April, when an R2 robot began its commercial pizza delivery service in partnership with Domino’s. Some customers ordering pizzas from the Domino’s Woodland Heights store will see the option to have their pies delivered by robot.

Customers can trace the progress of the self-driving vehicle on the Domino’s app and, when it pulls up outside their home, tap in a unique PIN on its touchscreen to access their order. Nuro is also operating in Houston with Kroger supermarkets and FedEx.

“One of the things we laugh about is how customers constantly talk to the bot,” Dennis Maloney, Domino’s chief innovation pfficer said. “It’s almost like they think it’s ‘Knight Rider.’ It’s very common for customers to thank it or say goodbye, which is great because that indicates we’re creating an engaging experience that they’re not frustrated by.”

Nuro team on test track during early validation in AZ, before first-ever public road deployment in Arizona. Image Credits: Nuro

Creating an experience, where people want to chat with their new robot neighbors instead of chasing them down the street with pitchforks, falls to Jones Satrom’s operations team. It has to delicately balance speed, safety, convenience and congestion, even as Nuro embarks on a growth spurt that will see robots spreading to other cities, states and partners in the months ahead.

Here’s how it manages that, and what the future holds for Nuro’s ever-so-gentle robot invasion.

Mapping the territory

Few people are as well suited to overseeing Nuro’s high-stakes robot rollout as Jones Satrom, who started her career as a nuclear engineer on an aircraft carrier and previously managed the integration of Kiva Systems’ robots into Amazon’s warehouses.

The first sign that your town is about to welcome a horde of Nuro robots will be the appearance of a fleet of human-driven Toyota Priuses modified with cameras, lidars and radars. Even as Tesla is ditching radars to rely solely on cameras for its advanced driver assistance system, Autopilot — which the company promises will someday evolve into an autonomous driving system — Nuro is committing to a full suite of sensors on a vehicle that will need to be much cheaper to build than an electric car.

“We fundamentally believe that lidar, cameras, radars, and all of these sensors will get to a very affordable price in the next few years as industry matures, so we have all of them,” co-founder Dave Ferguson said.

The cars’ first job is to thoroughly map the streets, intersections and surroundings. “It’s not quite as simple as: “Hey Google Maps, tell us where to go,” Jones Satrom remarked. “We rely on a deep level of detail in that map to manage how we navigate the city, what routing we should take and how the environment interacts with our AV [autonomous vehicle software] stack.”

Nuro uses modified Priuses to map and determine serviceability in areas it aims to launch in. Image Credits: Nuro

The Priuses (and ultimately the driverless R2 bots) are based out of a local depot where they can be easily cleaned, charged and maintained. Once the high-definition maps are produced and pass quality control, the Priuses switch into AV mode — still with a human safety driver on board but driving mostly autonomously.

At this point, Nuro is determining serviceability: Finding the shape and size of the area where its bots can operate safely. Serviceability includes everything from road markings and cellular service — necessary for transferring data and emergency teleoperation — to traffic infrastructure and even the weather.

“Snow, for example, is not in scope for the next few years,” says Jones Satrom. “But it even goes down to the level of how the AV stack performs at this particular traffic light, or that unprotected left-hand turn.”

Based on the data acquired by the Priuses, an algorithm determines the precise areas and streets where Nuro’s robots are safe enough to deploy. It’s here that Nuro’s decision to have only zero-occupancy AVs (ZOAVs) starts to pay off, says Jones Satrom: “If we take a somewhat longer route to be sure we’re safe, that’s probably okay for the goods. We have to be sensitive to when customers expect the goods, but there’s nobody actively sitting in the vehicle wondering why it’s turning right here instead of left.”

Because serviceability can change overnight, for anything from a revised road layout to seasonal weather, testing is a continuous process. California requires AV companies to report the number of miles they drive as well as any collisions each year. In 2020, Nuro’s vehicles covered more than 55,000 autonomous test miles — a modest drop from its pre-pandemic 2019 mileage of nearly 69,000.

Although Nuro has never filed an autonomous vehicle collision report in California, it has had at least one minor fender bender. Its 2020 report of disengagements — when its vehicles had to stop driving autonomously for some reason — includes one incident when “following [a] conservative yield, [the] vehicle behind made contact.”

Nuro aims for its bots to operate autonomously more than 95% of the time, says Jones Satrom, and the bots generally achieve that. But it is the last 5% that has proven so tricky for all AV companies. Consider that Google (now Waymo) has been building self-driving cars for over a decade now at a cost of many billions of dollars, and its vehicles can still struggle with unfamiliar situations.

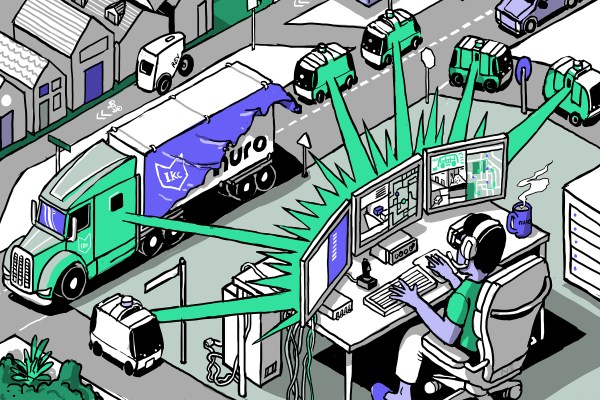

Nuro’s solution is not to expect the software to cope with everything the world can throw at it, but instead to fall back to a human teleoperations team of “guardian operators.”

Guardians of the grocery

“We don’t call them safety drivers — that’s an important nuance, because we don’t see them as the ones that are executing the driving,” says Jones Satrom. “We see our guardian operators as more of a safety net: There to respond to atypical situations or things that we didn’t necessarily anticipate.”

Teleoperations is the AV’s industry dirty secret. Despite cutting-edge sensors, powerful computers and sophisticated machine learning, even the best self-driving systems still occasionally require a human to get them out of trouble. While a few AV companies, such as Designated Driver, Phantom Auto and ZOAV startup Refraction AI, feature their remote operators proudly, most gloss over the human ghosts in their machines.

Nuro sits somewhere in the middle. Guardian operators are an established part of their commercial operations and have a strong role in product development, but Nuro remains shy of sharing many details of how they actually work.

“I won’t say it’s hush-hush, but teleoperations is a very sensitive topic,” said Lili Avalos, a guardian operator at Nuro who recently transitioned to a program management role. “Like most AV companies, we need teleoperations, but within the industry [there are a lot of] trade secrets. It’s a race to who can build this product first.”

A 2019 lawsuit between a recruitment company and one its contractors provides some insight into the scale of Nuro’s operations at the time. The recruiter had placed more than 100 “safety drivers, autonomous vehicle operators and command center operators” with Nuro in California, Arizona and Texas. (Nuro says it has hired hundreds of such employees in these states).

Guardian operators work out of Nuro’s facilities. They use screens that mimic the view from a traditional passenger car as closely as possible, although guardians can also access the bot’s 360-degree cameras if needed. While the bot does have a speaker to enable operators to respond to pleasantries (or curses) from customers and other road users, the guardian operators are not allowed to do so.

In fact, guardian operators are encouraged not to think of themselves as drivers at all, said Erick Soto, lead instructor for Nuro’s guardian operators. “We try to stay away from that. Assisting autonomy is the way we try to look at things. The driver is the autonomous system and we’re just there as the last line of defense.”

In the very rare instances where guardian operators are not available — perhaps during a communications outage — the bots will automatically enter a “safe state” where they pull over at the side of the road.

Guardian operators also work closely with Nuro’s hardware and software engineers. “My favorite part of the job is being an integral part of the feedback process,” said Avanos. “Features that we suggested get back to engineering, they build it, and then we see it. We’re there for the full lifecycle.” (A Nuro executive told TechCrunch that the R2 even has technology that prevents a person from stowing away in the bot’s compartments, but would not specify what it was).

At the moment, every bot has an individual guardian operator watching over it almost all the time, according to Jones Satrom. “We see that ratio of one-to-one going to one-to-many in the future,” she said. “But we really don’t plan on that happening for the next two to three years, especially as we’re in this early-stage deployment where safety and community engagement matter 100% more than anything else.”

Beyond teleoperation, Nuro, like most autonomous tech startups, still relies heavily on humans working behind the scenes. “Somebody has to plug and unplug the bot every day, as well as complete data offloading, routine cleaning, maintaining the vehicles and ensuring they’re ready to go,” Jones Satrom said. “From a total cost of operations perspective, labor will continue to remain one of the highest inputs.”

The power of partnership

Each new partner Nuro signs up brings a new set of requirements and new ways of working. “Each is optimizing for something slightly different,” said Jones Satrom. “We’re still building a playbook around each of our partners, with a product operations manager that spends time with them to understand how they work today and how will that work in [tomorrow’s] world of automation.”

The initial operations with a new partner use Nuro’s Prius fleet, where safety drivers can smooth over any gaps by talking with staff at the partner’s shop or facilities and letting them know they’ve arrived. The next stage involves eliminating many of those human touches and learning how to integrate bots into the partner’s existing operation.

This includes tracking the number of deliveries per vehicle per hour, which in turn is influenced by the bot’s speed and operating environment. Even the smallest details need to be recorded, such as the length of a charge based on the delivery profile or how long the tires last before needing inflation.

“We need to know how we’ll be able to support the peak delivery hours of the robot on a daily basis,” said Jones Satrom. The biggest impacts here typically come not only from the bot’s driving behavior, but also from surprises at a partner’s facility. “Sometimes the data shows we’re waiting 10 minutes at the store for them to load the bots,” she says. “Those are the types of things we work with the partner to understand how we can improve.”

Nuro’s R2 making a delivery at a sports arena in Sacramento during the pandemic lockdowns. Image Credits: Nuro

The COVID-19 pandemic, of course, was the biggest surprise to hit Nuro in recent years. “Before COVID, we were very much an R&D company,” said Jones Satrom. “Then we very quickly had to decide what services we could provide at this time of great need within our country, and how we could provide them.”

Nuro’s bots transported food, personal protective equipment, linens and other supplies at an event center in San Mateo and a sports arena in Sacramento that had been converted into temporary field hospitals for COVID-19 patients. The bots enabled truly contactless delivery, with public health workers just giving the vehicle’s camera a thumbs-up to access its compartments (often while grabbing a selfie).

“Helping out with that deployment was my proudest moment at Nuro,” said guardian operator Soto. “It really sunk in how big and how powerful this company could be.”

Jones Satrom credits the California response with accelerating Nuro’s transition to focusing on customer service: “It got everybody super focused on delivery and was a great driving force to orient the company around a use case that could actually support the COVID effort.”

One percent a day

“Shanghai does twice as many food deliveries every day as the United States,” says Cosimo Leipold, Nuro’s head of Partnerships. “We think this is because of the ratio of the cost of labor to the cost of goods. Asia is a canary in the coal mine for what will happen in the future when ultra-low-cost robotic delivery becomes possible.”

“When these things start being deployed, demand is going to go bonkers,” predicts John Lilly, venture partner at Greylock Capital and a Nuro board member. “The economics and the market fit are likely to be so strong that it will quickly make many other modes of goods delivery obsolete.”

But there remains a significant gap between Nuro’s ambitious plans with market-leading companies like Domino’s, FedEx and Walmart, and its single-figure bot deployments in Houston and Mountain View.

While Nuro now owns self-driving truck startup Ike, it has yet to reveal what, if any, plans it has to apply its technology to long-haul logistics.

If its robots are really going to cut emissions, improve safety and deliver hot pizzas at scale, they will have to learn to deal with new geographies and climates, apartment buildings and gated communities, ride-share scooters and ever more crowded curbs. While that learning continues, there seems little chance that Nuro will be able to eliminate humans from the loop anytime soon.

“As we learn more on the commercial operation side, there are so many minor issues and bugs and so many different edge cases,” says Avalos. “Honestly, the responsibilities of our guardian operators just keep growing.”

Those challenges don’t faze Jones Satrom, who feels the company is taking a measured approach to scaling operation. “We are focused on understanding what’s really required, making sure that we’re building the right hardware and then working those costs down and streamlining over time,” she says. “I joke with my team that we only have to improve by 1% every day and we’ll get there over time.”

“I have to always remind myself that autonomy is a very difficult problem to solve,” Avalos noted. “I think, why is this so hard? But we’re essentially building a product that hasn’t been done.”

Others might find that prospect terrifying, but for Nuro, it’s exciting and energizing.

Nuro EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Regulations

- Part 3: Partnerships

- Part 4: Operations

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.