As a startup founder, there will be three scenarios in which you’ll need to understand how to properly do a quality of earnings (QofE) if you want to maximize value.

The first scenario will be when you decide to raise a Series A and subsequent VC rounds, followed by when you do a strategic acquisition, and lastly, when you sell your company.

This post is a framework for how to think and organize your QofE and go through the most common items that you’ll want to keep top of mind for every M&A and private equity transaction you may be part of.

Why perform a QofE?

The goal of a QofE is to adjust the reported EBITDA to calculate a restated EBITDA that best reflects the current state of the company on an ongoing basis. It also presents a historical adjusted EBITDA that is comparable throughout the last two or three years.

QofE can have a significant impact on a company valuation for three main reasons:

- The adjusted EBITDA will be used by a buyer/investor as the basis for valuation (for companies valued based on an EBITDA multiple).

- The adjusted revenue will be used to recalculate the effective growth rate.

- The adjusted revenue and EBITDA will form the basis of forecasts.

With that in mind, every entrepreneur must understand how to properly form a view of what is the proper adjusted EBITDA and adjusted revenue of your company. It is common for founders in an M&A process to be unfamiliar with the notion of QofE and leave value on the table.

When performed by a professional transaction service advisory team, the quality of earnings is a result of a thorough review of all the documents generally available in a data room.

This breakdown aims to ensure that you won’t be that founder and that you’ll be armed to negotiate your company valuation on equal ground with your investors. If you are in the seller’s shoes, you will get the advantage of understanding how an experienced investor or buyer thinks. If you’re in the buyer’s shoes, you’ll benefit from understanding and valuing your acquisitions better.

How is a QofE professionally performed?

When performed by a professional transaction service advisory team, the quality of earnings is a result of a thorough review of all the documents generally available in a data room. These include, but are not limited to: Legal documentation, financial statements (P&L, balance sheet, cash flow), audit reports, management presentation and contracts.

When doing a QofE analysis, it’s key to consistently ask yourself: “Can or should this information translate into an adjustment of revenue or EBITDA, net working capital (NWC) or net debt?”

Why did we include NWC and net debt? That is because they often have an indirect impact on adjusted EBITDA. Think of an adjustment to the historical level of inventory. Less inventory likely means fewer storage costs. So if you adjust historical inventory, you’ll want to also impact your adjusted EBITDA.

On top of reviewing all the aforementioned documents, your QofE analysis will heavily rely on interviewing management. No matter how long you look at the financials, if you can’t have management confirm information or explain trends, you won’t be able to draw proper conclusions and understand the numbers.

Principles for efficiently building your QofE

- Automatically link everything you read and hear to potential QofE adjustments. This has to become second nature during the engagement.

- Always think about all the ways an event or item that qualifies for an adjustment impacts the financial statements overall. For instance, if the event impacted revenue, did it impact costs in some way as well?

- Make sure that the cost you are adjusting was not already offset by another accounting entry (i.e., had no impact on EBITDA).

- Make sure that the cost you adjust for was classified above EBITDA in the first place.

- Make sure that you can quantify each adjustment in the most objective and rational way. This is sometimes not possible and you may have to come up with a range.

- Put every adjustment back into the context of the whole company and ask yourself if in that context it makes sense to categorize that item as “non-recurring” or “non-normalized,” or whether in the grand scheme of things that item should be considered as part of business as usual.

- Make sure that your adjustment impacts the right financial year.

How to organize your QofE

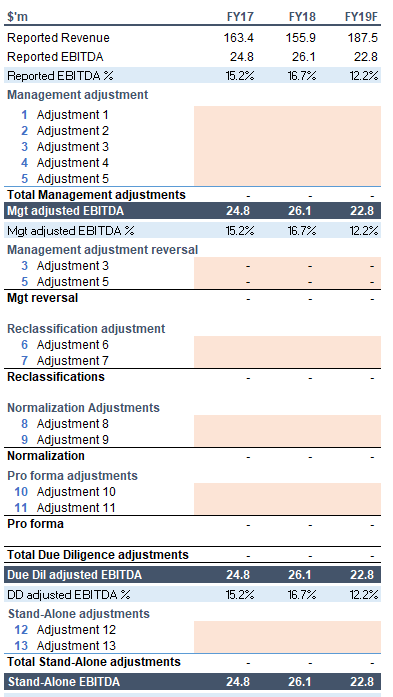

To structure your thoughts, I would recommend using the following framework followed by the Big Four accounting firms like PwC. When you’re dealing with professionals used to doing M&A deals, it will immediately look familiar to them.

- Review of management’s adjustment (if you are the buyer).

- Reclassification.

- Normalizations.

- Pro-forma/standalone adjustments.

- Other matters.

A clean presentation using that template would be as follows:

Image Credits: Pierre-Alexandre Heurtebize

Management adjustment reversal will only be relevant if the management has already come up with their adjusted EBITDA. In that case, you will need to understand and review each adjustment one by one and either agree and validate or disagree and reverse the adjustment.

Reclassification is generally the simplest adjustment that you can make, as they relate to items that should not be included in EBITDA in the first place. You will generally find these items by going through the trial balance and identify if any below-EBITDA items have been included above EBITDA, and vice versa. For example, it is not uncommon to see interest revenue included as part of total revenue or depreciation allocated to a certain cost category and remaining above EBITDA.

Normalization regroups different types of adjustments that aim at calculating an EBITDA “as if nothing uncommon had happened,” or in other words, what comes close to a maintainable EBITDA.

Pro-forma/standalone adjustments aim to reflect recent changes in the business to assess their full-year impact. For instance, clean the impact on EBITDA of any discontinued business, or on the contrary, assess the full-year impact of newly integrated business. If the transaction is a carve-out (i.e., only a part of the overall business is sold), you will also need to assess the additional costs that will be necessary to run it (e.g., overhead staff costs).

Other matters groups everything you should keep in mind because it can either have an impact on valuation or on whether to proceed with the deal, but that you cannot accurately quantify or you think including it in the adjusted EBITDA calculation would be too aggressive.

Normalization adjustments

These adjustments, in particular, can stem from a broader range of situations.

Accounting adjustments: There were accounting changes over the period and you want to present an EBITDA built consistently. Or it could be the case that accounting standards used by the company do not reflect well the reality of EBITDA and the market standard in transactions is to use a different approach (this often happens with the treatment of leases, for instance). It can also be simple accounting errors that have not been picked up by the audit team (this happens!).

One-off items: These can be items that impact EBITDA but are not supposed to happen in the future. For example, the company getaway in the Bahamas to celebrate its 50th anniversary.

Cut-off: Making sure that revenue and/or expenses impact the right period. Provisions and unused provision reversal, in particular, need to be closely reviewed.

Other costs: These can be related to the founders/current owners that are not reflective of the business post-transaction (e.g., owner going (again) to the Bahamas for personal leisure and charging it to the company).

Specific non-cash items: Stock-based compensation, for instance.

At the end of the day, this framework is here to help you structure your thought process. But in a real-life scenario, some adjustments may be qualified as normalization or as pro-forma, and as long as the adjustment in itself has been spotted and calculated correctly, the classification difference won’t be the end of the world.

Most common QofE adjustments

To help you perform your analysis, let’s review some of the most common QofE adjustments I have come across during financial due diligence engagements that you can use as a checklist when you’re in an M&A or fundraising process.

1. Reclassification

Interest costs and depreciation and amortization hidden in other lines of costs: I’ve seen both cases in several engagements when I was working in FDD at PwC. The first case occurs when the company reports interest costs as part of the “other cost” line, which generally ends up being included above EBITDA. The second case happens when management accounts are built by destination rather than by nature.

This means, for instance, that management’s P&L can have a “vehicle costs” line and when you look at a breakdown of this account, you can see that it includes car depreciation, which by definition should be included below EBITDA.

2. Normalizations

Transaction costs: All the costs associated with the current transaction. For example: Lawyer costs, DD costs, extra accounting costs, etc. It can also relate to past M&A transactions.

Consultant fees: It is not unusual for companies to get consultants to help them on a one-time restructuring project, to help them define their strategy or implement new software. It is acceptable to restate from EBITDA as long as the one-off nature of that cost can be demonstrated.

Also, do not mismatch one-off consultant costs with costs of contractors hired on a temporary basis to cover for a shortage of staff, but who effectively provided work that is directly part of the everyday lifecycle of the business.

One-off events: Or any event that relates to the once in a lifetime companywide trip to Vegas for a week to celebrate an iconic anniversary. If you can show in the accounts that this was once in a lifetime and not the usual annual company retreat, then you can adjust for that amount. Not before asking yourself what amount you should adjust for, though. Did that week-long Vegas trip replace the annual weekend company retreat to Vermont, which still costs a few dozen thousand dollars each year?

If yes, then you will only adjust for the cost portion above the past few year’s average.

Severance packages paid: If for some reason some employees were laid off and this was an unusual move based on historicals, then costs related to the severance packages can be adjusted in the QofE. When you see a severance package, also have the reflex to ask about potential litigation (e.g., ex-employees suing the company).

Fire/natural disasters: A raging fire destroyed half the Montana factory last year, which stayed closed for three months, meaning three months of revenue were lost. How do you adjust for that?

First, ensure that you have support in the numbers that three months of revenue were indeed lost, and take into account any sales catch-up effect in the first months when the factory came back online.

Second, don’t just take the amount of lost revenue as your adjustment. If these sales had been made, the company would have had to pay for and recognize the COGS (raw materials) associated with the production and sale of the product. So effectively, the EBITDA impact amounted to the loss in gross profit, not to the lost revenue.

Finally, ask if there was an insurance policy in place and whether the company received any type of compensation recorded above EBITDA. It could also have taken the form of government help or subsidy. Make sure you allocate your adjustments to the right periods.

Calculation of provision for warranty/inventory — any statistical provision: It is common in several industries for a company to calculate a default warranty provision or inventory write-off provision based on statistics. In essence, the logic is to say, “out of 100 items that we produce, we know that on average five will never be sold.”

The reality is that, like with any measure that is discretionary and gives management some freedom of interpretation, this can be slightly manipulated. In these cases, it is a good idea to dive into how these provisions are calculated and understand if there was any change of policy in the period under review, or if there was any abnormal unused provision released over the period impacting EBITDA.

Year-end cut-off/revenue and cost attribution: Revenue (and potentially costs) cut-off between two periods relates to a conscious accounting choice to allocate revenue to one or the other fiscal year.

Take a three-month consulting contract, for instance. In the first month, the company plans to be in observation, they will build tools and recommendations the second month, and in the third month they will implement these tools. Let’s assume the total contract value is $30,000.

One way to do the cut-off is to allocate (recognize) $10,000 of revenue per month. But what if the second month requires 50% of the resources the company dedicates to the whole process? Should not 50% of the revenue be allocated to that month?

In theory, yes, to match the revenue and the costs (if not, you will see some strong swings in gross profit), but in reality, management may play with the possibility to allocate revenue differently.

Hence, it should be part of your QofE process to review the allocation of revenue and costs to make sure that they are allocated to the right period. This is important because it will have an impact on last year’s EBITDA and also on the growth rate. In industries like the SaaS market, the growth rate is the main factor in determining the valuation of a company.

Donations and charity: It is common, especially in the U.S. or Australia, to have owners donate to charity or their local football club through their company. If you can ensure that this has no repercussions on the business and will be discontinued post-acquisition, it is perfectly OK to include this item in your QofE.

R&D expenses: R&D expenses can be capitalized. When it relates to engineers developing products that will then be part of the intangible assets, the value of the salary of these engineers is added back to the EBITDA as part of the capitalization of the costs and the costs booked as assets.

Think about it as if the company had paid an external firm to develop a platform. They could have booked this expense directly as capex. This is generally accepted practice, but will also depend on the industry you’re in and the country. However, make sure that you review the calculation of the capitalized costs just to make sure that non-R&D costs are not included in there.

Bonuses: Understand the bonus structure and see if there was an exceptional bonus paid to management. If bonuses were bigger this year just because the revenue of the year was above budget, then it would be harder to argue that it is not business as usual.

Straight-lining of rent: There can be different arrangements regarding rent. Some common ones include a period of free rent (say first three months free), while others can include an agreed upon rent increase schedule.

For a fair treatment of the rent costs and fair allocation, you generally want to calculate the total cost of the rent over the lease period and divide that by the number of years of the lease. This should be your adjusted rent, and your adjustment will simply be the difference between adjusted and reported.

Discount for early payment (either given or received): Let’s assume clients benefit from a legal delay to pay the company 30 days after invoicing. If that company offers a 2% discount if the invoice is paid within 10 days, this can be seen as a financing item since effectively that 2% discount is the cost to finance the company’s net working capital.

This is equivalent to not offering the discount and borrowing the money from a bank and paying interest on that amount. This means you can argue that discounts should be adjusted from EBITDA. However, in such a case, there should be a net working capital and net debt adjustment as well.

3. Pro-forma

New product launched/product discontinued: A new product has recently been launched or a flagship product (that may have been loss-making) has been recently discontinued.

You’ll need to look at the context to assess whether this company launches a new product every year and often discontinues products. Or whether it was an exceptional event, in which case you will calculate a pro-forma adjustment to assess the full-year effect of the change.

For example, let’s assume the company financials go from January to December, and a new product was launched in March 2020. There are two ways you can legitimately adjust the EBITDA. First, you can adjust the EBITDA for all the costs associated with the product launch, and second, you can annualize the profit made over the nine months the product was launched.

If the product has a ramp-up period, you can be even more aggressive in your adjustment. If the sales of the product doubled each month for the first three months and then stabilized, you can argue that the correct pro-forma adjustment should be calculated based on the last six months of sales.

Full-year impact of acquisition/divestiture: We can apply the same logic as above here, except that in this case, it makes sense 100% of the time to incorporate the full EBITDA of a newly acquired business.

If a business was acquired three months before fiscal-year end, and the accounting principles used dictated to only include these three months of revenue and costs, you will add a pro-forma adjustment to reflect the financials. The financials would be reflected as if the acquired business had been operating within the group for the past 12 months.

The same logic applies for divestitures whose financial impact should be adjusted for. If the divested business was loss-making, the adjustment will increase adjusted EBITDA versus reported.

New C-suite hire: If a new C-suite individual has recently been hired, you can ask yourself whether you should reflect the full-year impact of the salary of that person in your QofE. There is always potential debate about it, because that person, especially if they are paid well, is expected to deliver some kind of value to the company that is not reflected yet in the financials, and adjusting only for the salary cost of that person might be a bit aggressive.

It may be easier to argue for positions that do not have a direct impact on the top line. If a director of compliance was hired three months ago because the company has reached the stage where having a compliance director is compulsory, then it may be fair if you would like to reflect on the full-year impact of hiring them.

Another scenario where you can adjust is one where, for instance, the CFO resigned and for four months their role was covered by the team and the CEO, and a new CFO just got hired. In that case, you can argue that there are four months of CFO salary missing from the EBITDA.

Final recommendations

The list above is non-exhaustive and there exist a fair number of additional QofE adjustments that can have a significant impact on a company’s valuation, especially when the company is valued at a higher EBITDA multiple.

Top management needs to be aware of these potential adjustments, because at the end of the day, if you are CEO or CFO, you are in the front row of what happens in the company and will be best positioned to see what adjustment can apply to your situation. As a manager, it’s always good to be aware of these things, because eventually, they will come up during the rounds of negotiation.

However, financial due diligence requires a lot of work, can be fairly technical and needs a specific set of skills and knowledge. For these reasons, your accountant or CPA may not be best armed to advise you if they lack M&A experience. We highly recommend that you get advice from experienced financial due diligence professionals.

But at least you should now have the language to entertain a conversation with a more experienced buyer or seller!