The global venture capital bet on neobanks is massive. London-based Starling Bank has raised more than $900 million, per Crunchbase. The same data source indicates that Chime has raised $1.5 billion. Monzo has raised nearly $650 million. And the list goes on: E-commerce-focused neobank Juni raised $21.5 million last month. Novo, an SMB-focused neobank, raised $41 million in June. Nubank has raised $2.3 billion. And FairMoney has locked down more than $50 million.

On and on and on.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

But despite our general inclination to lump banking-focused fintech providers that serve consumers, business customers or both into a single bucket, there’s wide divergence in how the various neobank players are performing in the market.

Back in August 2020, The Exchange noted that many neobanks were racking up steep losses. Our read at the time was that the capital being poured into the fintech category was being invested aggressively in the name of growth. Based on recent results, that view is holding up.

But not all neobanks are the unprofitable enterprises that they once were. Chime indicated in September 2020 that it generates positive, unadjusted EBITDA. That’s a stricter profit metric than the one that Lyft used recently to claim its ascendance into the realm of profitable companies; Lyft posted positive adjusted EBITDA in its most recent quarter, but burned cash to fund its operations and posted a wide net loss in the period.

But not all neobanks are the unprofitable enterprises that they once were. Chime indicated in September 2020 that it generates positive, unadjusted EBITDA. That’s a stricter profit metric than the one that Lyft used recently to claim its ascendance into the realm of profitable companies; Lyft posted positive adjusted EBITDA in its most recent quarter, but burned cash to fund its operations and posted a wide net loss in the period.

And Starling Bank reached what it describes as profitable territory in October 2020. Things have changed since our first look into neobank results.

The trend of positive neobank news continued this June, when Revolut reported its recent financial performance. The company did post rather negative aggregate results for the 2020 period. But when we drilled down into its quarterly results, we saw the picture of a fintech company scaling its gross margins and revenues while nearly reaching adjusted net income neutrality by Q4 2020. We were impressed.

This morning, let’s add to our running dig into neobank results by parsing recently released data from Starling Bank and Monzo. As we’ll see, although some neobanks are managing to clean up their ledgers and work toward profits — or reach profitability — not all are in the black.

Monzo, Starling Bank results

We’ll start with Monzo results. You can find the British neobank’s most recent results here, and its 2020 results here, if you are so inclined. Monzo’s fiscal year closes at the end of February, so its 2021 results are from the 12-month period concluding at the start of March this year.

The data we’re observing, then, is somewhat dated. This is the price that we pay for having more access to neobank numbers than what we can drum up from most private companies. European neobanks report their results on a somewhat regular basis, providing a key window into the category’s performance. The tax is that we are forced to look further behind us than we’d like.

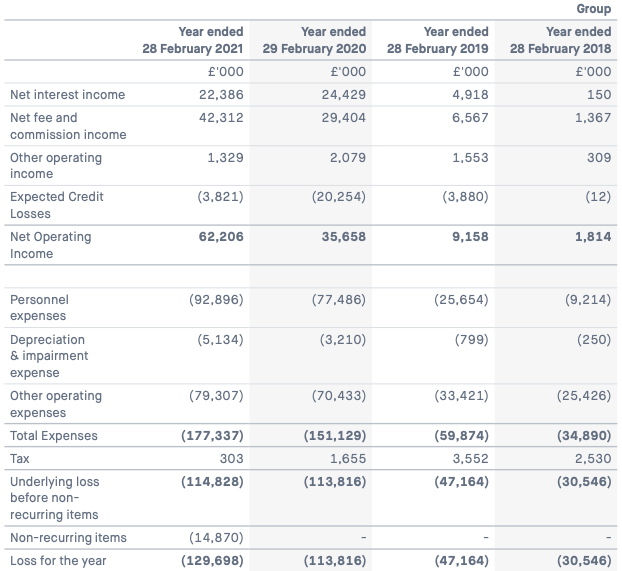

All the same, here’s the key data from the company regarding its most recent fiscal year:

Image Credits: Monzo annual report

Note that time flows right to left and that every number presented is in thousands of pounds. A result of 10,000 is actually 10 million pounds. Got it? Great.

At first blush, it appears that Monzo’s business grew massively, from net operating income of 35.7 million pounds in the year-ago fiscal year to 62.2 million pounds in its fiscal 2021, a gain of 74%. However, the company’s revenue growth was more modest, from 67 million pounds to 79 million pounds from its fiscal 2020 to its fiscal 2021. That’s a more modest 18%.

From a different perspective, Monzo had revenue of around 8.75 million pounds in December, a figure that we calculate from its annual run rate of 105 million pounds at the end of 2020, a figure that it based on revenues in the final month of the year. You can start to estimate the company’s 2021 revenues from that figure.

The differential between the company’s revenue growth (slower) and expansion of its net operating income (faster) appears to be a swing in the company’s credit losses. What drove the decline in credit losses? Monzo slowed its lending pace in its last fiscal year. In its own words, Monzo “reduced new lending to [its] customers, which helped [it] stay within [its] risk appetite during the uncertainty of the pandemic.” Cool.

Regardless of how you prefer to vet the company’s growth — revenue or net operating income — what matters more for our work are the numbers a bit lower in the table. While Monzo’s expenses grew more slowly than its net operating income, the company’s underlying loss before special items was marginally worse in its fiscal 2021 than its fiscal 2020. And inclusive of non-recurring items, it was far worse.

So Monzo in a way had a good fiscal 2021, slowing expense growth, limiting credit losses and growing its revenues. But what the company failed to demonstrate was operating leverage; as its revenues scaled, its losses did not fall.

You can argue this a few different ways, I am sure, but Monzo appears to remain an example of a neobank still fully in its investing phase. By that, we mean that it is still spending heavily to finance its growth, and that historical growth has yet to generate enough gross profit to truly reduce its losses.

Now, Starling.

Recall that Sterling became profitable in late calendar 2020. Though what counts as profit among startups and unicorns is flexible. We consider the phrase “profitable” from startups to more mean cash flow positivity, or non-negative adjusted EBITDA, because in most cases that’s what’s being discussed.

Regardless, we have two data sets from Starling. The first is from a 16-month period covering the first of December 2019 through the end of March 2021. Why? Starling is moving to a new fiscal calendar, so its current reporting is a bit wonky. Regardless, for that period, here are some notes from the company:

- “For the period to 31 March 2021, our revenue rose by nearly 600% to £97.6 million, from £14 million for the previous period ending 30 November 2019, while our loss more than halved to £23.3 million from £52.1 million.”

Operating leverage! That’s very good. Solid growth and falling losses are what you want to see among late-stage technology upstarts.

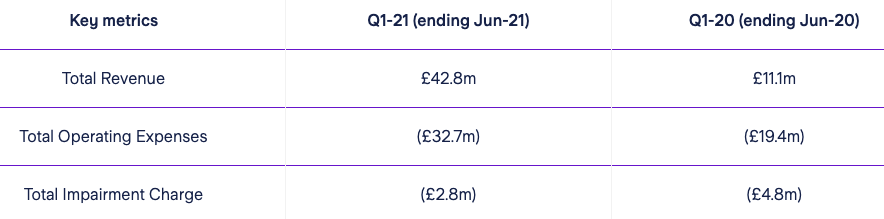

But Starling also dropped a fiscal Q1 2021 update, covering the company’s calendar second quarter. This means we have pretty up-to-date data for Starling, or at least far fresher data than what we have from Monzo. Here are the key bits:

Image Credits: Starling Bank trading update

That’s a near quadrupling of revenues, and a pleasant inversion of costs and revenues; Starling’s revenues far outstripped its operating expenses in the June quarter, something it was far from managing in the year-ago calendar Q2.

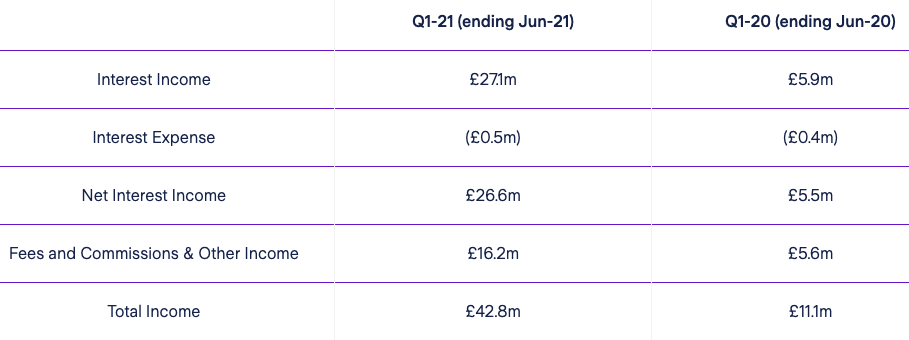

Breaking down its revenue a bit more, here’s the data:

Image Credits: Starling Bank trading update

Hot dang, right? That’s all rather good.

What drove the huge gains in Starling’s incomes? A 50% gain in retail accounts, from 1.2 million at the end of June 2020 to 1.8 million at the end of June 2021, and a sharper doubling of business accounts from 180,000 to 374,000 over the same time frame.

Those business customers appear to have driven lots of lending activity at Starling, which saw its total lending rise from 836 million pounds in the year-ago June quarter to 2.3 billion pounds in this year’s calendar Q2. Two types of lending, in particular, the Bounce Back Loan Scheme and Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme, drove huge volume for Starling.

Note that we are not trying to say that Starling only managed its growth thanks to corporate lending as part of the COVID-19 cycle; the company has more than one strength. But it does appear that Starling was very active in small-business lending, in part thanks to COVID-related schemes. Capitalizing on opportunity is not a sin, though next year’s year-over-year comps may be harder for Starling to best than its calendar 2020 results are proving.

Starling is a reminder that neobanks can not only claim profitability but also demonstrate operating leverage. With Revolut’s strong end-of-year 2020 performance in hand, we can see that at least a portion of the neobanking world is financially stable enough to consider public offerings. Monzo still has some work to do, but its numbers appear more like outliers than category warnings today.

Neobanks! Perhaps all that money wagered on them will come good.