Shares of Square are up this morning after the company announced its second-quarter earnings and that it will buy Afterpay, an Australian buy now, pay later (BNPL) player in a $29 billion deal. As TechCrunch reported this morning, Afterpay shareholders will receive 0.375 shares of Square in exchange for their existing equity.

Shares of Afterpay are sharply higher after the deal was announced thanks to its implied premium, while shares of Square are up 7% in early-morning trading.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Over the past year, we’ve written extensively about the BNPL market, usually from the perspective of earnings from companies in the space. Afterpay has been a key data source, along with the yet-private Klarna and U.S. public BNPL outfit Affirm. Recall that each company has posted strong growth in recent periods, with the United States arising as a prime competitive market.

Most recently, consumer hardware and services giant Apple is reportedly preparing a move into the BNPL space. Our read at the time was that any such movement by Cupertino would impact mass-market BNPL players more than niche-focused companies. Apple has a fintech base and broad IRL payment acceptance, making it a potentially strong competitor for BNPL services aimed at consumers; BNPL services targeted at particular industries or niches would likely see less competition from Apple.

Most recently, consumer hardware and services giant Apple is reportedly preparing a move into the BNPL space. Our read at the time was that any such movement by Cupertino would impact mass-market BNPL players more than niche-focused companies. Apple has a fintech base and broad IRL payment acceptance, making it a potentially strong competitor for BNPL services aimed at consumers; BNPL services targeted at particular industries or niches would likely see less competition from Apple.

From that landscape, let’s explore the Square-Afterpay deal. We want to know what Afterpay brings to Square in terms of revenue, growth and reach. We also want to do some math on the price Square is willing to pay for the company — and what that might tell us about the value of BNPL and fintech revenues more broadly. Then we’ll eyeball the numbers and try to decide if Square is overpaying for Afterpay.

What Afterpay brings to Square

As with most major deals these days, Square and Afterpay released an investor presentation detailing their argument in favor of their combination. Let’s dig through it.

Square is a two-part company. It has a large consumer business via Cash App, and it has a large business division that offers payments tech and other fintech services to corporate customers. Recall that Square is also building out banking services for its business customers and that Cash App also serves some banking and investing functionality for consumers.

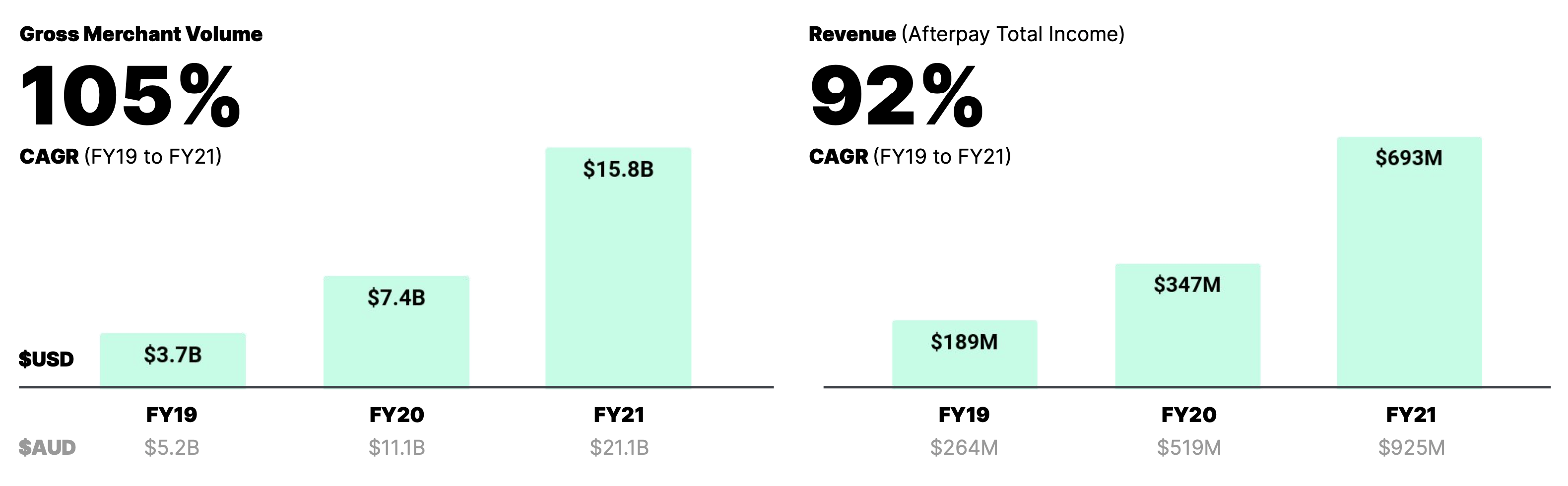

Afterpay, in contrast, is a BNPL player with its own merchant network and customer base. It has also posted very rapid growth in recent years. Per the deck:

Image Credits: After Pay

That’s an attractive business to buy because Afterpay is not only consuming an ever-larger chunk of global e-commerce payments (left chart) but turning that growth into quickly scaling revenues (right chart).

How do the two companies fit together? Afterpay brings something to each part of Square’s business: Afterpay’s business customers will become Square customers, growing the latter company’s merchant footprint while also expanding its product lineup. And by buying Afterpay, Square will add a BNPL option for its merchants to offer goods and services to its consumer user base.

More simply, with PayPal, Klarna, Afterpay, Affirm and a host of smaller BNPL providers proving that customers like fee-based installment loans for online purchases, Square had to join the fight or miss a trick. PayPal is already seeing strong results with its own BNPL service. Square could build, or it could buy. Because Afterpay had tech and both corporate and consumer users, it fits neatly into Square’s two-part business.

Even more, Square has seen its value soar in recent quarters, giving it lots of new wealth that can be used for a big deal. So why not toss around some of that dosh and snag Afterpay? The synergies, which are akin to business star signs, are aligned.

The acquiring company explained this dynamic in its deck by noting that “Square and Afterpay combine complementary merchant ecosystems,” and that “Cash App and Afterpay combine complementary consumer ecosystems.” While I don’t want to ever be too kind to corporates, those comments seem reasonable.

There are other nuances. Cash App is mainly a U.S.-based phenom. Afterpay has a more global consumer user base. And Square sees more than 85% of its transaction volume in the United States. Afterpay, in contrast, does more than half of its business outside the United States. Afterpay, then, will help make Square a more globally relevant company.

Finally, the deal may also help accelerate Square’s growth to a modest degree.

The companies note in their presentation that Square’s gross profit — a metric that the company now favors after bitcoin sales to consumers skewed its revenues — grew 71% in the four quarters ending June 30, 2021. Afterpay, in contrast, grew its gross profit by 96%. Afterpay is a much smaller company than Square in revenue terms, so don’t expect the latter company to find an entirely new gear. But the deal could be a nice tailwind to gross profit growth at Square all the same.

So far, so good. The products fit, the global footprints have synergies and Square may be buying a little growth at the same time. With Afterpay aboard, Square can more comprehensively fight not only PayPal and pure-play BNPL firms, but is de-risked against Apple’s eventual joining of the installment credit market for consumers as well.

But did Square pay too much for Afterpay?

What about cost?

The Square-Afterpay deal has an implied value of $29 billion. There’s nuance to the number, but the figure provides enough context for the all-stock deal to meet our needs. To understand what premium Square is paying for the smaller company, let’s quickly calculate some multiples. We’ll compare annualized run rates from recent periods for a few BNPL companies, and then divide the resulting figure by their current market cap, or private-market valuation, to see how expensive the Square deal is compared to some market comps.

- Klarna: In the first quarter, Klarna reported 2,951,907,000 Swedish Krona in revenue (up 42% year over year), or a run rate of 11,807,628,000 Krona. In dollars, that works out to a run rate of $1.38 billion at current conversion rates. The company was most recently valued at $45.6 billion. That works out to a run rate multiple of about 33x. Now, this number is a bit high; we lack Q2 numbers from Klarna, and, presumably, it grew in the last quarter. But it’s what we have, so it’s what we calculated.

- Affirm: Annoyingly, we only have calendar Q1 results from Affirm as well. Regardless, the company’s revenue for the March 31, 2021, period was $230.7 million (up 67% year over year). That works out to a run rate of $922.8 million, with the company worth $14.93 billion as of the time of writing, meaning Affirm has a multiple of 16.2x. Again, this number is too high because the company has grown since its first quarter.

A few more caveats: Klarna is a private company and is thus being valued by a slightly different set of investors. When it was last valued, it did so after raising huge chunks of cash that it will deploy, perhaps boosting its growth rate. In contrast, Affirm is already public. It also presents some revenue concentration risks that may weigh on investors’ minds when they value it; Affirm is a key provider for Peloton, which drives a large portion of its revenues.

Now let’s do the same exercise with Afterpay at the $29 billion that Square will pay:

- Afterpay: Afterpay dropped its full fiscal year results today. They are not incredibly useful. The company’s disclosed fiscal Q3 2021 numbers align with the calendar Q1 period, which we hoped would prove illustrative. Sadly, those results are only inclusive of GMV figures. Agh. So, we’ll have to use Afterpay’s fiscal 2021 aggregate revenue figure for our work. Afterpay generated revenues of $693 million in its fiscal year ending June 30, 2021. At a $29 billion price tag, the company is worth 42x its revenues.

Naturally, that multiple is exaggerated because we’re not using a run rate as the denominator of our market cap/revenue calculation. But I think the figure still works for our purposes, as the delta between Klarna and Affirm multiples and Afterpay’s own indicate that Square is paying more for its BNPL purchase than what other players in the space can command on their own, even making allowances for our somewhat wonky comparisons.

Square is paying a premium. But is that premium too rich? Probably not.

The U.S. company is valued at around $120 billion this morning, making this deal worth around a quarter of its present-day value. That’s a lot, but not if Square’s strategic plans bear out.

Returning to the deal logic, recall that Afterpay brings global revenues, global users and a more diverse merchant network to Square. It would have had to spend to derive those assets over time. Square is willing to pay up to snag them now. And Afterpay will not get cheaper in time; the company was considering a U.S. listing, which would have brought it more capital access and thus more resources from which to grow. So, buy it now and pay a lot, or buy it later and pay more.

Finally, the price that Square will pay doesn’t offend because the company could not afford not to have a BNPL solution long term. PayPal has already spent time and capital on its own. If Square was to start from zero today, or near zero, it would be a lagging player in a crucial and growing consumer fintech market. It doesn’t want to play catchup, especially with Apple looming in the distance.

So, spend a bunch of its equity value that the market has awarded it since early 2020 — Square’s stock has appreciated from around $52 per share in March 2020 to $264 and change today — to at once de-risk its future, grow its geographic footprint, accelerate its gross profit growth and avoid irksome product work?

What else is the value of being a public company if not the ability to throw around paper value to make big deals? This one is not cheap, but hardly too expensive as to be unconscionable.