The irony of 911 is that it’s a number that everyone knows (at least in the United States), and yet, no one really thinks about it. Few of us will dial 911 more than a handful of times in our lives, and even when we do, we will meet the police officers and paramedics who respond, never the 911 call taker who handled the dispatch. These systems and the people behind them garner meager attention, whether from Congress, state legislatures, the public or anyone else outside the emergency response community.

Except, that is, for Michael Martin.

RapidSOS’ story is one of a mission, a community, a team and a dream that every emergency should have the best chance to be resolved as positively as possible.

He, along with Nick Horelik and Matt Bozik very early on, became fascinated by the complexity and lack of innovation in the sector. “Uber had just come out. I could press a button and get a car. Why can’t I just press a button and get an ambulance? And then it sparks this curiosity,” Martin said. He sought knowledge, but for such a critical system, information was sparse. “The Wikipedia article on George Clooney is way longer than the one on 911,” he noted.

So began a nearly decade-long journey with RapidSOS that would see Martin and his team first attempt to build a consumer-safety app called Haven before pivoting exclusively to helping dozens of tech companies, including Apple and Google and device companies like SiriusXM, connect to a myriad of 911 software vendors. Along the way, they experienced the full vagaries of startup life, frenetically pivoting from product to product as they tried to get consumers to even care about emergencies.

It wasn’t easy, and it took years before the company finally hit its stride. But RapidSOS’s story is one of a mission, a community, a team and a dream that every emergency should have the best chance to be resolved as positively as possible.

Indiana: The callroads of America

Martin grew up outside the rural town of Rockport, Indiana, population about 2,500 today. His mother was the local doctor, and he and his brother habituated to the openness and ennui of rural farming life. “We grew up on 35 acres of land; we had an enormous garden and a little hobby orchard and stuff like that,” he said. “We had ‘Drive-Your-Tractor-To-School Day.'”

Yet, with an early entrepreneurial streak, he wasn’t content to drive just a tractor to school. Describing himself as “a standout nerd,” Martin and a friend were intrigued by the idea of building efficient cars. “We did this competition to get real high gas mileage … I think we got over 2,000 miles per gallon in this car.”

The process of building the car would have echoes on RapidSOS years into the future. “It was another story where we had no money; no one wanted to do this with us because it was super nerdy,” he recounted. “Even back then, I was cold-calling all the local businesses, asking them to donate, because we had to raise close to $100,000 for this.”

As they were building the car, they realized they needed a custom windshield to fit the body’s frame. That required heating the glass to high temperatures, but in a small town, there weren’t that many places with the right equipment to do that. “We went to the local pizza guy and he let us, before he opened, run it through his pizza oven, which was a disaster because we were kids and we didn’t know what we were doing. So we partially melted it and there was smoke everywhere,” he said.

The dominoes of life took a more conventional turn as Martin headed to Carleton College in Minnesota for undergrad, followed by stints in investment banking at Piper Jaffray and then venture investing at Braemar Energy Ventures. By 2013, though, his mind was redirecting toward entrepreneurship. After years of working in venture capital and banking, he wanted to learn more about building companies, which led to Harvard Business School in the fall of 2013.

Before he went, though, he got the wheels turning on RapidSOS. He linked up with Matt Bozik, an associate investor colleague at Braemar, and formed RapidSOS, LLC, in Indiana in April 2013. Bozik, who sat on the company’s board from inception until a little more than a year ago, hasn’t had much of a public role with the company, and instead helped it with finance and fundraising over the years, including a stint as the company’s CFO in 2019.

Part of Martin’s interest in emergency response, according to a podcast interview a few years ago, was triggered by an incident while walking in East Harlem when he had just moved to New York after college. “It was about 1:00 in the morning and it was deserted at 111th Street. I’m walking back from the subway and I noticed this individual is following me. And so I tried to increase pace, change sides of the street; he did the same. And I realized that there was very little I could do in that moment,” he said. He realized that there should be a better way to get help faster than fumbling with a phone and explaining to a call taker where he was.

Drive-by iteration

Besides learning about building businesses, Harvard Business School also served as a laboratory for building RapidSOS, both literally and figuratively. Martin met his co-founder and current RapidSOS CTO Nick Horelik, a Ph.D. student in nuclear engineering from MIT, and the two started working out what they could do in emergency response.

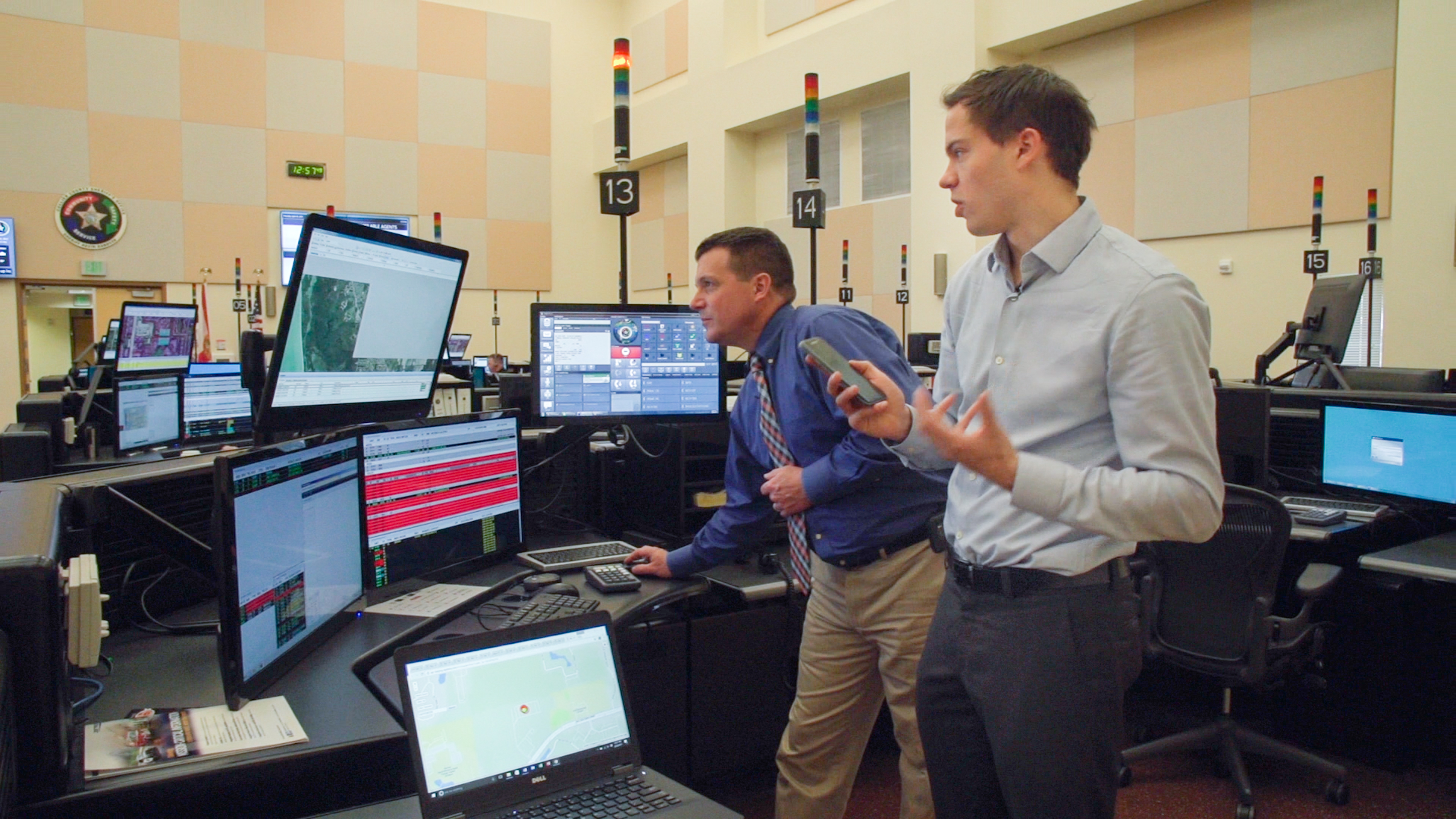

RapidSOS co-founders CEO Michael Martin and CTO Nick Horelik at a 911 dispatch center. Image Credits: RapidSOS

For the first few years, RapidSOS focused on solving a chicken-and-egg problem. It needed to develop a government data platform that could bring richer data into public safety answering points (PSAPs), or what are colloquially called 911 call centers. With that platform in place, other products could be developed to take advantage of these new capabilities and underwrite the rest of their business.

The duo first focused on the government platform, quickening the pace in the summer of 2014 when RapidSOS joined the Harvard iLab, the university’s startup incubator and education center.

That summer diverged for the founders. Horelik, along with a fleet of interns, holed up at the iLab’s co-working space to work on the engineering puzzles. They were able to get the GPS location of a phone onto the legacy screens of 911 call takers, which Martin described as “a huge breakthrough for us at the time.” There wasn’t much else they could show given the constraints of the systems, but that was enough of a working MVP to start building new services on top of.

An early photo of the RapidSOS team when it was working out of the Harvard iLab. Image Credits: RapidSOS

Meanwhile, Martin started driving across the country to talk to 911 call takers and learn from potential clients what they needed. He wanted to hit the National Emergency Number Association conference in Nashville while also stopping by Dallas to interview a major 911 industry figure. So as he drove across the country, he stopped in cities big and small to connect with the staffs at PSAPs while trying to find friends’ couches to crash on. “I had no money, right? Both in personal life, because I was paying $90,000 a year to go to grad school, and then the business had no money either,” he recalls. “I had to negotiate with [NENA] to try to get this free student pass.”

He cold-called administrative lines for police stations and emergency centers, asking to come in. “I would say I’m a grad student at Harvard researching 911, and I want to guess it was 80%+ where people would say ‘Yes’ and make time,” he said. He kept a spreadsheet during the day, and at night, would call Horelik with his findings to help the engineering team iterate on product development.

Feedback was as diverse as the PSAPs that dot America, but one theme quickly became clear. “This community, they actually are leaning in on this. They’re going to work with this stupid grad student who had some idea here,” Martin said. Indeed, the trip would, by at least one metric, be quite successful: 44 PSAPs in North Central Texas would end up being among the first beta users of the company’s government platform.

RapidSOS co-founder and CEO Michael Martin went on a spree of visits to 911 centers in the summer of 2014. It’s a pattern he’s continued to the present day. Image Credits: RapidSOS

For all his enthusiasm, RapidSOS wasn’t viable building just for local agencies. “When we went out and interviewed all these 911 agencies, the level of challenges that they were facing: Staffing challenges, operational challenges, no funding — it was just … like a forgotten chain in our emergency response infrastructure,” Martin said. The company has never charged governments for the use of its software, a business model we will explore further in the next part of this EC-1.

Moving Haven and Earth to fundraise and launch a consumer product

Having built a small bridge into the 911 world with its data platform, the next challenge for RapidSOS would be building and marketing other products that actually took advantage of the platform — and drove revenues.

One area of interest early on was to try to sell data to financial institutions. From my TechCrunch article in June 2015:

Longer term, Martin expects that the company’s data around emergencies will allow it to offer a predictive analytics platform that might be of interest to Wall Street investment funds and insurance companies.

That wouldn’t pan out, but Martin still feels that the insurance industry should have been more engaged early on. “In just a pure capitalistic way, no one cares more about how fast the ambulance arrives than your life insurance company,” he said in our recent interview. The company trialed a product called RapidSOS Predict to “preempt emergencies before they occur,” which didn’t come to fruition.

Instead, the young company soon converged on two products that would integrate with the back-end 911 data platform. One was an app dubbed Haven, which would allow anyone to push a button to call 911 and immediately send critical information to the call taker. In addition, the startup also worked on a product it called GeoAlert that was designed for universities and public safety agencies to send mass emergency alerts to people within a circumscribed geographical area.

Between the two, the company placed huge emphasis on Haven. If the quintessential question of building a company is “If you build it, will they come?” then for RapidSOS, the equivalent at the time was “If you offer them a button, will they use it?”

Some of the first beta users of Haven were first responders themselves, and feedback was constant at the time. Tracy Eldridge, who was a 911 call taker based near Boston, “downloaded the app, and she did like 50 test calls, so many test calls that our system flagged it — it was like a DDoS attack,” Martin said.

“It’s funny. We’re in a tech company and our engineers are working like 11 [a.m.] to midnight, but the 911 folks always want to meet at like 6 a.m.,” he continued. “So I come in with my backpack at 6 a.m., dressed up in rural Massachusetts, and she just has a stack of printouts of how our data came in. And she’s just marked it all up and all this stuff, and it was just amazing.” Martin later offered her a job, and she worked at RapidSOS for four years before launching her own consulting and media business late last year.

All that feedback didn’t solve two key problems, though: The company needed money, and it needed traction.

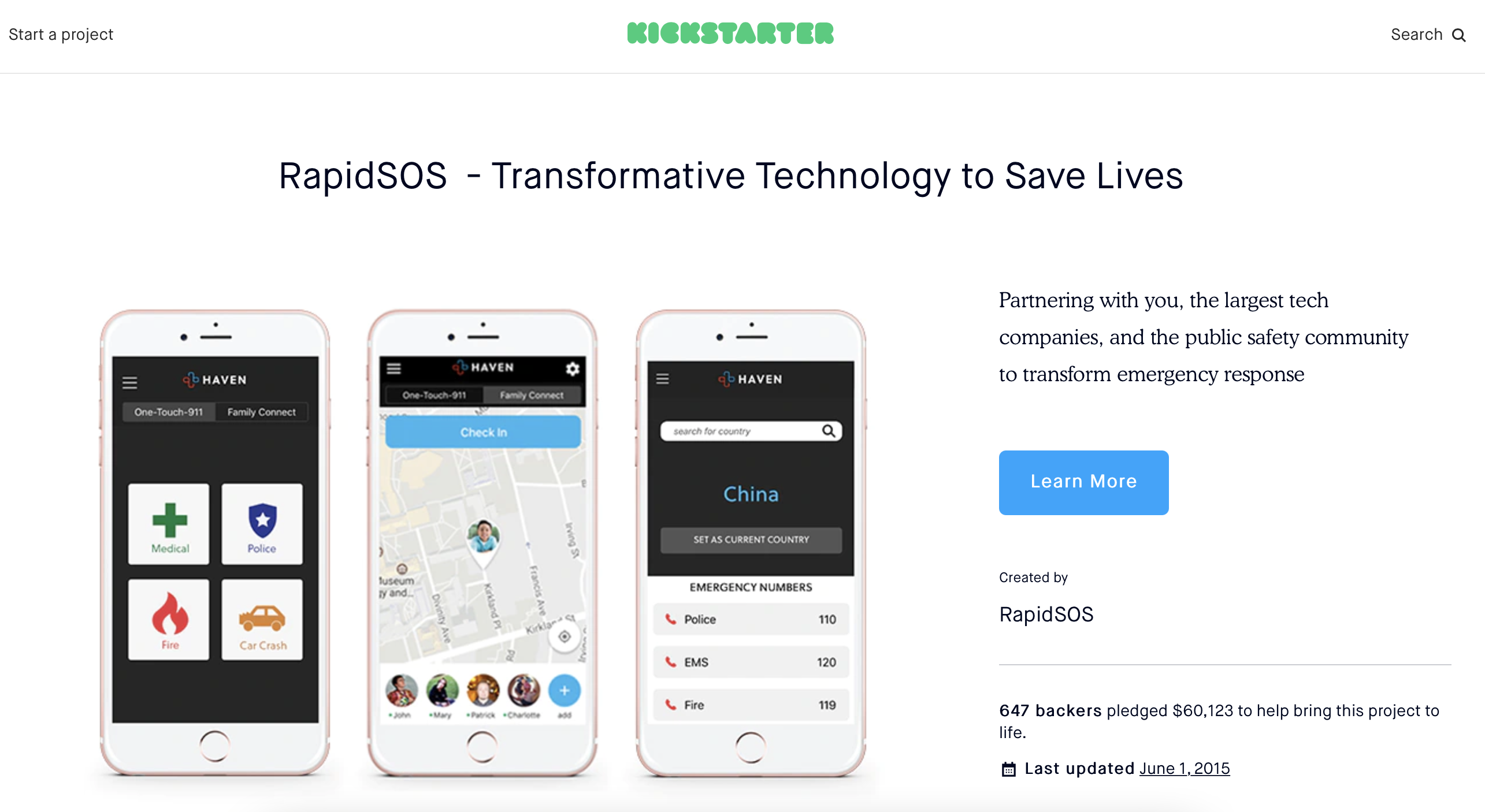

Martin scrounged together a variety of funds through startup competitions, winning the Harvard President’s Challenge and HBS New Venture Competition along with a variety of other startup competitions, netting nearly $500,000. The team also launched a Kickstarter in March 2015, ultimately garnering a bit more than $60,000 when it closed in June.

RapidSOS’ Kickstarter fundraiser, with screenshots of its Haven app prominently displayed. Image Credits: RapidSOS

The sums, though, were a bit of a disappointment. “I was like, ‘Man, this thing is going to go viral!’ We’d won all those competitions … and so we poured every penny into this [Kickstarter] video because we’re like, ‘We just need to nail the video and it’s just going to be incredible,’ basically,” Martin said. But it didn’t quite work out. In the end, we “just could not get anyone to donate to this project.”

He even tried to stuff the Kickstarter box a bit to bring some momentum to the flagging campaign. “I went to the bank [and] I think I got like $500 in $1 bills, and I was this 26-year-old kid, so the bank teller was like, ‘It’s shady,'” he recounted. He went to Harvard’s dining halls and handed out the dollar bills paper-clipped to business cards with the RapidSOS Kickstarter link on it. “All these privileged kids at Harvard, only like 20%” actually offered the dollar back to the Kickstarter, Martin laughed. “In hindsight, I think there were strong signs that maybe the consumer app wasn’t going to work.”

Nevertheless, the company trudged on, launching a closed beta of Haven in December 2015, and opening the app to the public in mid-2016. It was free to download, but in the company’s pursuit of a business, it ultimately targeted a price point of $2.99 per month for a subscription.

The launch didn’t go well, as those earlier signs perhaps foretold. Martin recounted his experience on launch day:

We had like half the company out across New York. We gave everyone 500 business cards that had, “Get Haven,” or whatever. It was six months free. And so, I stood in Grand Central [Station in New York City] at the base of the escalator that comes up, where it’s like a bottleneck, and I’m just giving these cards to everyone. And I was like, “Yeah! We’re going to have a million users after today!” For two hours there, I’m just forcing these cards on people. So, I finally take the escalator up myself after I’d given them all out, and three-quarters of them are in the trash bin at the top of the escalator.

Hustling marketing tactics aside, consumers just weren’t interested in downloading a separate app to have on hand in case of an emergency. Part of the magic of 911 is that users never have to prepare in advance — when something happens, they click three buttons and they are on the line. Haven required foresight — and few wanted to pay a monthly subscription to boot.

Fortuitously, the company secured a $5 million Series A funding round led by Dan Nova at Highland Capital Partners around the same time as the company’s public launch, which would help tide it over as it scrambled to recover from its lukewarm reception. In the following months, it managed to raise another $6.4 million from a range of undisclosed individuals as well as Motorola Solutions, which has a large government software and hardware telecommunications business.

But even with cash in the bank, the lack of uptake from consumers was a wake-up call that RapidSOS’ business model was fumbling. “It became clear we had to figure out how to get this embedded in every phone,” Martin said. “Then it became this pivot to try to think about who’s on every phone and how do we work with them. Obviously, Uber had a big base. Google, Apple were the holy grail.”

The company had a new strategy: offering a free 911 data platform to PSAPs while charging tech companies for using an API to easily connect their devices to 911. It was a bold bet — one entirely divergent from where the company was standing. RapidSOS’ efforts in 2017 and 2018 increasingly turned to its data platform and building partnerships with tech companies and 911 industry vendors, and ultimately, Haven was shut down in late 2018 along with GeoAlert.

“We massively whiffed on our whole business model, game plan, and [Highland] just kept putting more and more capital in and believed in it,” Martin said. The firm would indeed double down, leading a $16 million funding in early 2018 even as the future of the business remained uncertain. Ultimately, the company’s new focus would find substantial traction as we will see in the next part of this EC-1, where we explore RapidSOS’ products and current business model.

RapidSOS EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product and business

- Part 3: Partnerships

- Part 4: Next-generation 911

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.