This afternoon Robinhood filed to go public. TechCrunch’s first look at its results can be found here. Now that we’ve done a first dig, we can take the time to dive into the company’s filing more deeply.

Robinhood’s IPO has long been anticipated not only because there are billions of dollars in capital riding on its impending liquidity, but also because the company became something of a poster child for the savings and investing boom that 2020 saw and the COVID-19 pandemic helped engender.

The consumer trading service’s products became so popular and enmeshed in popular culture thanks to both the “stonks” movement and the larger GameStop brouhaha, that the company’s public offering carries much more weight than that of a more regular venture-backed entity. Robinhood has fans, haters, and many an observer in Congress.

Regardless of all that, today we are digging into the company’s business and financial results. So, if you want to better understand how Robinhood makes money, and how profitable or not it really is, this is for you.

We will start with a more in-depth look at growth and profitability, pivot to learning about the company’s revenue makeup, discuss a risk factor or two, and close on its decision to offer some of its own shares to its users. Let’s go!

Inside Robinhood’s growth engine

Before we get into the how of Robinhood’s growth, let’s discuss how big the company has become.

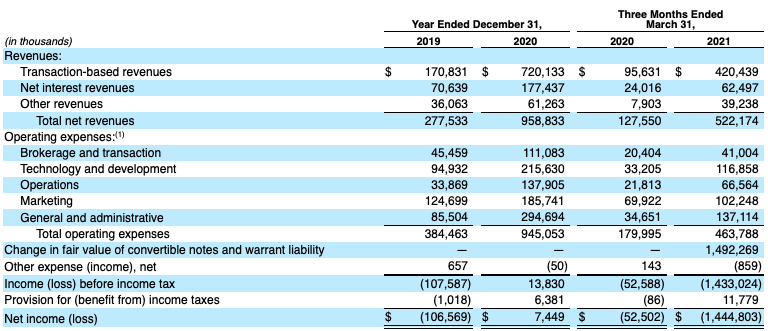

The fintech unicorn’s revenue grew from $277.5 million in 2019 to $958.8 million in 2020, which works out to growth of around 245%. Robinhood expanded even more quickly in the first quarter of 2021, scaling from year-ago revenue of $127.6 million to $522.2 million, a gain of around 309%.

Those are numbers that we frankly do not see often amongst companies going public; 300% growth is a pre-Series A metric, usually.

Returning to our point about how famous the company has become, we can see in its financial performance — tied as it is to user activity, which we’ll get to shortly — why Robinhood’s IPO will prove noisy. It’s going public because of rapidly scaling usage from consumers, usage that in turn helped the company’s size flat explode in the last year.

Now let’s talk profitability. Here’s Robinhood’s main income statement, which we’ll both need to discuss the company’s red and black ink:

Image Credits: Robinhood

In 2019 Robinhood’s net losses were not small, with the firm posting a $106.6 million deficit, inclusive of tax costs. However, the next year’s growth turned that all around for Robinhood, with the company managing to end the year just in the black — in percent of revenue terms — with net income of $7.4 million.

The company’s 2019 net loss, however, was not spread out amongst its quarters in a uniform fashion; net losses ramped from around $12 million in both Q1 and Q2 2019 to $38.4 million and $44.6 million in Q3 and Q4 of the year, respectively.

That unprofitability, however, stuck with the company through the first quarter of 2020, which saw Robinhood post a net loss of $52.5 million. The company erased its previous unprofitability with net income of $57.6 million in the second quarter. And the company’s final two quarters worked out to a net few million in profit, leaving the firm with modest net income on the year.

The start to 2021 was different. Scaling from Q4 2020 revenue of $317.5 million to $522.2 million in a single quarter, Robinhood swung from net income of $13 million in the final three months of 2020 to a flabbergasting $1.44 billion loss. That figure, however, was driven by changes in the value of “convertible notes and warrant liability,” which will need some unpacking.

Here’s the company’s explanation: “Change in fair value convertible notes and warrant liability was due to the mark-to-market adjustment of the convertible notes issued and warrant granted in February 2021,” the period of time in which the company raised debts, likely forcing it to adjust the value of quite a lot of underlying shares in its business. The result? A huge noncash loss for the period.

Two more notes on the company’s financial health. First, adjusted profits. While the first quarter of this year looks awful for Robinhood in GAAP terms, using a more startup-friendly profitability lens helps make a stronger case. In adjusted EBITDA terms, Robinhood’s 2020 profits swell to $154.6 million, and in the first quarter of this year it posted $114.8 million in non-GAAP profits. That’s probably the largest gap from GAAP to adjusted profitability we’ve ever seen.

Where does all that revenue come from?

Robinhood generates revenue from three key categories: transaction-based, interest and other.

Transaction revenues, per Robinhood, “consist of amount earned from routing customer orders for options, equities and cryptocurrencies to market makers.” In the case of stocks, the company generates PFOF revenues as known. Notably the company also earns “transaction rebates” for its crypto trades.

Interest revenues are somewhat obvious, with the company’s net interest top line being a balance of income from “securities lending transactions,” as well as interest income from user margin loans, cash and “deposits with clearing organizations.” Robinhood pays interest on its credit facilities, as it uses them.

What’s “Other,” then? Robinhood Gold, the company’s subscription product, among other smaller incomes.

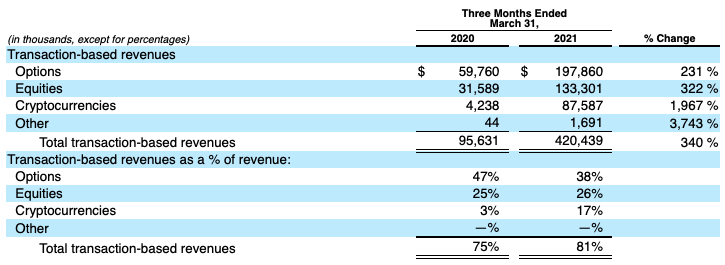

You can see top-line numbers for each revenue category in the above-embedded income statement. Let’s go one level deeper now, starting with transaction incomes:

Image Credits: Robinhood

We can quickly see that Robinhood’s options incomes still reigned supreme in contribution terms during the first quarter of 2021, albeit at a loss of some luster to equities-generated top line. Why? GameStop, we reckon, and other stocks that likely helped Robinhood post record results in the period for the line item.

The key growth story for the company in the period is its crypto results, which shot from dismissible to material over the last 12 months. How did that happen? Robinhood has an answer. From its risk factors:

A substantial portion of the recent growth in our net revenues earned from cryptocurrency transactions is attributable to transactions in Dogecoin. If demand for transactions in Dogecoin declines and is not replaced by new demand for other cryptocurrencies available for trading on our platform, our business, financial condition and results of operations could be adversely affected.

Yep. Dogecoin. You love to see it.

Closing out our revenue discussion, Robinhood is bone-grafted onto Citadel Securities, which accounted for 34% of its total revenue in 2020, up from 29% in 2019. Indeed, revenues from the company from its top four market-making revenue sources were worth 75% of its total revenue last year, up from 62% in 2019.

Finally, this

The final thing we want to examine is Robinhood’s decision to sell a chunk of its IPO shares to its own users. From the company’s S-1 filing, here’s the official language regarding the decision (emphasis added):

We expect the underwriters to reserve approximately 20% to 35% of the shares of our Class A common stock offered by this prospectus for RHF, acting as a selling group member, to allocate for sale to Robinhood customers through our IPO Access feature on our platform. Any such sales will be made at the same initial public offering price, and at the same time, as any other purchases in this offering, including purchases by institutions and other large investors, and in accordance with customary broker-dealer practices and procedures. The final number of shares of our Class A common stock in this offering that will be reserved for allocation to Robinhood customers will be determined at the pricing of this offering and will be based on the level of demand from Robinhood customers and all other purchasers in this offering in accordance with the broker-dealer book building process.

You can view this in one of two ways. On one hand, perhaps Robinhood expects its users will be more likely to hold onto its shares, perhaps helping it manage first-day trading swings. On the other, perhaps Robinhood wants to ensure that it can get a bunch of shares trading hands amongst a less savvy investing group than IPOs tend to sell stock to; which argument you put more stock in depends on your view of the company, we reckon.

All told Robinhood is a singluar company in terms of rise, consumer footprint, corporate incomes, net losses and more. It’s a whole kettle of fish. More when we get an updated filing.