Startups are stories of feverish dreams and obsessive fears. Short of hearing it from the source, a glimpse into the inbox of a founder would be the best way to experience the travails they endure on the way to building a business. A customer finally makes a purchase, a VC invests or walks away, an employee signs their offer letter — all of the major and minor milestones of a startup are communicated via that now-ancient medium of email.

Current Klaviyo users may be surprised to hear that email was not a part of the initial product.

Email’s ubiquity is only part of the story, though. It’s also a symbol of freedom: The last social platform that remains relatively open and free from the clutches of a single monopoly owner. It’s a market rife with entrenched incumbents, but one that simultaneously continues to invite founders to find some new take on this venerable communications channel and make it better for everyone.

That was the mission that Andrew Bialecki and Ed Hallen undertook when they founded Klaviyo back in 2012. What they perhaps didn’t bank on was just how long of a route they were about to take — or how many rejections they might find in their own inboxes from accelerators and VCs who never thought a new generation of email service providers could make it.

So they bootstrapped, kept things lean. They debated canceling dinners to pay the bills when customers churned. And along the way, they built a special startup that is today valued at a whopping $4.15 billion. Klaviyo is the story of how two scrappy, inexperienced entrepreneurs set out to build a lifestyle business — and ended up creating an email titan.

Racing to the starting line

Klaviyo’s origin story sounds a bit like the generic advice given by every book on entrepreneurship. Andrew Bialecki — he goes by AB — had a need that no existing company filled. So, he started a company to address that need.

It began with what he calls a side hustle: a website devoted to cataloging the dates and locations of running races. Bialecki had the technical chops to build it, but the data wasn’t already available online and he needed race organizers to provide it. That, in turn, meant he needed to let them know his site existed and constantly follow up to make sure they were using it.

“I realized I’m on the phone with people and it’s never going to scale. After a while, I was working on that while I was at another startup, and I said I have two options here. Either I can go all-in on road races, or all-in on the problem: ‘How do we help these businesses connect with the people using their software or products?’” recalls Bialecki.

By then, he already had a co-founder in mind. Bialecki had been a student together with Ed Hallen at MIT, but the pair actually met while working at Applied Predictive Technologies (APT), a Washington, D.C. tech consultancy.

“I’d read all those books on, hey, when you’re looking for someone to start a business with, you want someone with similar values who’s also complementary,” says Bialecki. “I’d known he was kind of interested in starting a company, and we had really complementary skillsets. I loved the engineering and design and product, and he was a big product guy too, but was used to working with customers and clients.”

An email company that didn’t (initially) do email

Current Klaviyo users may be surprised to hear that email was not part of the product that emerged. Instead, Bialecki and Hallen built a database to collect all the e-commerce data that was falling through the cracks.

“Once we really talked to a lot of e-commerce people, it was clear there were long-standing problems,” says Hallen.

Bialecki adds, “There are facts you know, like their name, their email address, their favorite color or something they told you about their birthday. But some of the harder stuff was, jeez, how many times has this person visited my website, bought something from me, what products did they buy and how is that trending over time? Were they a really frequent customer that dropped off the face of the Earth?”

As they spoke to customers, the founders realized that handling customers’ data and making it useful to them was going to be critical to Klaviyo’s success. It just so happened that gathering data matched well with their experiences working at APT.

“We had a ton of experience stitching together data sources,” says Hallen. “We took that expertise and put it as our foundation. What’s the most broken, largest market, and let’s really tie data to it, not as an afterthought.”

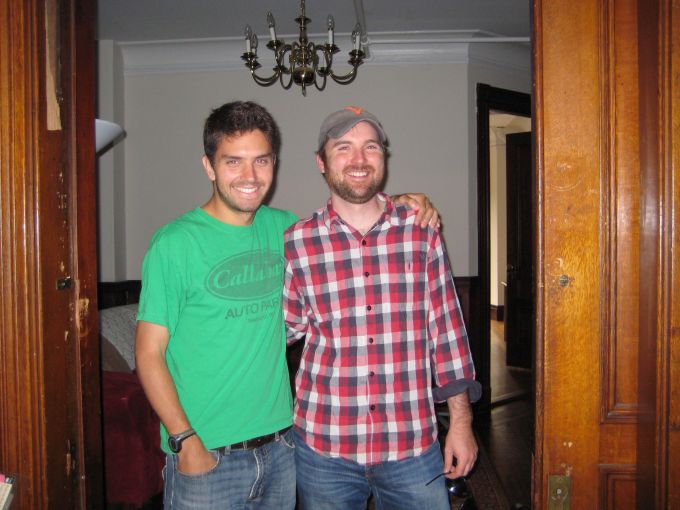

Klaviyo’s two co-founders Andrew Bialecki and Ed Hallen in July 2012. Image Credits: Klaviyo

What that required, in practical terms, was spending the initial months building a custom database to store the disparate data types that come up during e-commerce transactions — events, documents and object data models. Conor O’Mahony, who joined the company in 2018 as chief product officer and departed this month to become an advisor, says that the company’s early time investment in its database laid the foundations for its later success in scaling up.

“If Klaviyo started today, we would take the same path. We would build our own custom data storage and processing environment,” says O’Mahony. “While it may not be immediately visible to the outside world, these capabilities are a key part of our differentiation.”

By focusing on customers and avoiding competitive landscaping, Bialecki and Hallen ignored the many companies that, by 2012, could credibly claim to collect e-commerce data. Instead of puzzling out where they fit in the market, they spent their time interviewing potential customers about ways Klaviyo could help, using a simple litmus test: Would the interviewee actually give them money to fill that need?

“I remember we had conversations where we’d describe what we were doing, which was not Klaviyo, and we’d say great, can you give us your credit card? ‘Oh, it just sounds good, it’s not what we need.’ That whole process was a hallmark of the early days,” Hallen says.

Bootstrapping in for the long run

Although venture funding wasn’t the first thing on the co-founders’ minds, they did take steps to find external help. Their first office was in an MIT-owned building that housed multiple other startups, giving them some insight into what their peers were doing. “Everyone there was talking to VCs, talking about the competitive landscape. We weren’t,” says Hallen.

The Great Dome and Killian Court of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Image Credits: Owen Franken / Getty Images

A few months after starting though, they began applying to accelerators in the Boston area. The email responses were not encouraging.

“They’d give you like 10 or 15 or 20,000 dollars, which at the time was months and months of capital. We applied to three or four of those in May to June of 2012, and we got rejected from all of them,” recalls Bialecki. “We had this perspective of: ‘Oh, if we can’t put together a good enough pitch for these summer programs, how will we make a pitch for a quarter of a million dollars?’ They’ll poke all these holes because we haven’t figured it out.”

Rather than sharpening their pitch — such as finally doing that competitive research — the co-founders decided to put their heads down and continue with what they’d been doing already.

“Bootstrapping Klaviyo, it came out of this, ‘Hey, if we are super disciplined about finding a problem that someone will pay us to solve, we have a real company’. Once we went through that process, we had paying customers; just two of us, running super lean … it was easy to envision a world where, let’s just keep doing what we’re doing, we don’t need the money,” says Hallen.

The co-founders also had role models that suggested bootstrapping was the way to go. APT, where they’d both worked, was bootstrapped and had become a well-respected tech company on the East Coast. Bialecki’s extended family also owned a decades-old insurance business that had never taken outside funding. “I always loved how enduring that business was, that it was multigenerational, a real culture to the people who worked there,” says Bialecki.

When David didn’t notice Goliath

Klaviyo was making enough revenue to support its co-founders, but the two kept an eye out for additional customers. The company’s future course was set in a pivotal conversation Bialecki had with a customer as they walked along the Charles River near MIT.

The Charles River in Cambridge, MA. Image Credits: Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg via Getty Images

“He said what they really needed was to import that data into their email platform,” Bialecki recalls. “At the time, they were paying $100 per month. I said, do you care if we built it ourselves? He said no, but they need to design the email, send thousands at a time. I said, yeah yeah, I think we can do that. And I asked how much they’re paying for the email part, and he said, oh, $200 a month. I said, my gosh, I have this one customer I could grow by 3x if I just add this one piece.”

From one perspective, Bialecki’s answer sounds like pure hubris — companies like Mailchimp and Constant Contact already looked like they had locked down the email market. Of course, Klaviyo had already shown that it wasn’t interested in competitive research. In its own David versus Goliath story, David simply failed to notice that Goliath was there.

Klaviyo CEO Andrew Bialecki. Image Credits: Klaviyo

Not that adding email was easy. “Email is an awesome tech because it’s so decentralized, but it hasn’t evolved in decades. Designing something for it is awful,” says Bialecki. “I remember the first time we tried to send 100,000 emails at a time. It took three hours and people were really annoyed because it was so slow.”

Both Bialecki and Hallen, though, seem to have a talent for staying focused. And the lack of any outside help may have ultimately benefited the company.

“There was never anyone saying, hey, let off the gas on that and tell me a bigger story, or paint this picture for investors. Never a world where all these investors were competing over us or people telling us we were great,” says Hallen.

Instead, three years passed as Bialecki and Hallen stayed focused on the product and slowly grew revenue to the point that they could begin hiring and building up the lifestyle business they’d envisioned.

“We were playing with house money”

Bootstrapping is not unique in Klaviyo’s vertical. Mailchimp, for instance, has never taken outside funding in its 20 years as a company.

Klaviyo likely could have continued on indefinitely without funding, too. By 2015, the company was bringing in a million dollars per year in revenue and had a handful of employees. Bialecki and Hallen thought they might double their revenue by the end of the year. Instead, revenue quadrupled to $4 million.

“The entirety of 2015, we’d discuss, what is Klaviyo? Now that it’s profitable, should we just be the owners and be happy? Or do we want to double down and take every dollar, put it back into the business, and go for broke?” says Bialecki, recalling discussions he’d have with Hallen.

One experience they had with a major client in late 2014 helped seal the decision. “In early December, they called and said: ‘Hey, we’re sorry, but you guys just can’t keep up with us’,” Bialecki recalls. He and Hallen were heading that night to a “fancy dinner” with the company’s intern for a holiday party to celebrate the strong year. “I remember turning to Ed and we just got this gut punch, that in five minutes someone called us and said, ‘Hey, you’re just not cutting it’, and by the way, that’s 20% of your revenue. I said, ‘Should we cancel this dinner? Can we even afford this?’ That was probably the biggest setback we’d had so far,” he said.

Klaviyo co-founder Ed Hallen. Image Credits: Klaviyo

After numerous discussions, the founding pair finally decided that they’d seek funding. “We were playing with house money in terms of the luck we’d had, our upbringings, and the opportunity to even start a business. Why don’t we just go for broke?” says Bialecki.

The timing was good: Klaviyo had come a long way since its days of being rejected from accelerators. Michael Medici, managing director at Summit Partners’ Boston office, remembers beginning to hear about the company around the same time.

“The company had gained some notoriety, because Andrew and Ed were both really well-perceived entrepreneurs and engineers … [Bialecki] was also somewhat famous, because he would not really entertain a lot of dialogue with VCs or investors or investment bankers,” says Medici.

The perception that Klaviyo didn’t need VC money only served to heighten investor interest, and by the end of the year, the company had secured a $1.5 million angel round led by Accomplice, a Boston VC specializing in early funding.

“That first year … was a lot of firefighting”

Klaviyo’s early Boston office in June 2015. Image Credits: Klaviyo

During a roughly three-year period, from about 2016 to 2018, Klaviyo transformed from what it was — a product originally built by just two people who were simultaneously juggling business development and customer service for an active user base — to its more expansive, modern form.

“When I first started, there was not a product team at all,” says Alexandra Edelstein, now a group product manager at Klaviyo who joined the company in late 2015. “We were still only maybe 25 people, and I was wearing a lot of hats … that first year, 2016, was a lot of firefighting, figuring out problems.”

Alexandra Edelstein, a group product manager and early employee of Klaviyo. Image Credits: Klaviyo

Although Klaviyo’s founders don’t regard email as the heart of the platform — that honor is reserved for the database — many of the fires Edelstein and her co-workers were fighting seemed to revolve around the complexities of using a 50-year-old communication channel.

Deliverability, for instance, is a reputational score that determines whether emails are allowed to arrive normally and not be relegated to a separate marketing or spam folder. As new customers flooded in, some of them used Klaviyo in ways that caused its deliverability to plummet. The startup’s earliest employees had to scramble for solutions, such as limiting sending for newer users and adding guidelines and how-tos to prevent low-quality emails.

Solving foundational problems like deliverability or the lack of help documentation brought the company into a new phase — one in which its design and product decisions made it the leading communication software for many marketers.

It was also the beginning for new leadership at Klaviyo. In 2017, Hallen decided to leave the company and Bialecki formally became CEO.

Until then, the two had more or less shared the role. “We figured, when it was just the two of us, we didn’t need titles like CEO,” recalls Bialecki. But while building the company, Hallen had met his future wife — and then she’d moved to the West Coast. After a period of traveling back and forth, he says, he saw the writing on the wall.

“At some point, it was clear one of us had to be the CEO, and also that we were building a long-term Boston company,” says Hallen, who remains on the board and regularly communicates with Bialecki. “We believed in having a team in one place, which feels a little anachronistic at this point.” (The company has been working remotely during 2020, like most others.)

In the space of just a few years, rejection emails turned into offers, and customers were increasingly knocking on the door to buy Klaviyo’s product. But to make a lasting difference, the company had to do more than just offer a slightly better product than its competitors — it had to completely reinvent what email marketing could be in the burgeoning world of social media. Owned marketing and transforming e-commerce would be key to Klaviyo’s growth, and that’s the next topic we’ll turn to in part two of this EC-1.

Klaviyo EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Business and growth

- Part 3: Dynamics of e-commerce marketing

- Part 4: Lessons on startup growth

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.