Pokémon GO was created to encourage players to explore the world while coordinating impromptu large group gatherings — activities we’ve all been encouraged to avoid since the pandemic began.

And yet, analysts estimate that 2020 was Pokémon GO’s highest-earning year yet.

By twisting some knobs and tweaking variables, Pokémon GO became much easier to play without leaving the house.

Niantic’s approach to 2020 was full of carefully considered changes, and I’ve highlighted many of their key decisions below.

Consider this something of an addendum to the Niantic EC-1 I wrote last year, where I outlined things like the company’s beginnings as a side project within Google, how Pokémon Go began as an April Fools’ joke and the company’s aim to build the platform that powers the AR headsets of the future.

Hit the brakes

On a press call outlining an update Niantic shipped in November, the company put it on no uncertain terms: the roadmap they’d followed over the last ten-or-so months was not the one they started the year with. Their original roadmap included a handful of new features that have yet to see the light of day. They declined to say what those features were of course (presumably because they still hope to launch them once the world is less broken) — but they just didn’t make sense to release right now.

Instead, as any potential end date for the pandemic slipped further into the horizon, the team refocused in Q1 2020 on figuring out ways to adapt what already worked and adjust existing gameplay to let players do more while going out less.

Turning the dials

As its name indicates, GO was never meant to be played while sitting at home. John Hanke’s initial vision for Niantic was focused around finding ways to get people outside and playing together; from its very first prototype, Niantic had players running around a city to take over its virtual equivalent block by block. They’d spent nearly a decade building up a database of real-world locations that would act as in-game points meant to encourage exploration and wandering. Years of development effort went into turning Pokémon GO into more and more of a social game, requiring teamwork and sometimes even flash mob-like meetups for its biggest challenges.

Now it all needed to work from the player’s couch.

The earliest changes were those that were easiest for Niantic to make on-the-fly, but they had dramatic impacts on the way the game actually works.

Some of the changes:

- Doubling the players “radius” for interacting with in-game gyms, landmarks that players can temporarily take over for their in-game team, earning occupants a bit of in-game currency based on how long they maintain control. This change let more gym battles happen from the couch.

- Increasing spawn points, generally upping the number of Pokémon you could find at home dramatically.

- Increasing “incense” effectiveness, which allowed players to use a premium item to encourage even more Pokémon to pop up at home. Niantic phased this change out in October, then quietly reintroduced it in late November. Incense would also last twice as long, making it cheaper for players to use.

- Allowing steps taken indoors (read: on treadmills) to count toward in-game distance challenges.

- Players would no longer need to walk long distances to earn entry into the online player-versus-player battle system.

- Your “buddy” Pokémon (a specially designated Pokémon that you can level up Tamagotchi-style for bonus perks) would now bring you more gifts of items you’d need to play. Pre-pandemic, getting these items meant wandering to the nearby “Pokéstop” landmarks.

By twisting some knobs and tweaking variables, Pokémon GO became much easier to play without leaving the house — but, importantly, these changes avoided anything that might break the game while being just as easy to reverse once it became safe to do so.

GO Fest goes virtual

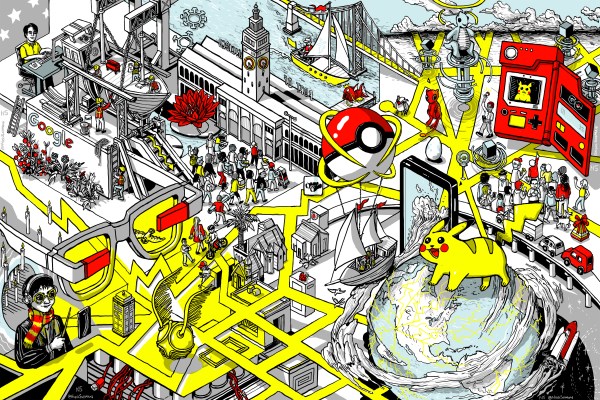

Like this, just … online. Image Credits: Greg Kumparak

Thrown by Niantic every year since 2017, GO Fest is meant to be an ultra-concentrated version of the Pokémon GO experience. Thousands of players cram into one park, coming together to tackle challenges and capture previously unreleased Pokémon.

The first GO Fest was a bit of a disaster, with overloaded cell towers and logistical stumbles leading to an angry crowd, refunds and lawsuits. They tried again in 2018 and 2019 with considerably more success … but of course, that now-proven game plan wasn’t going to work this year.

Like most other large, in-person events, GO Fest had to go virtual, quickly. And it … mostly worked?

Instead of gathering everyone in a park, Niantic shipped the experience worldwide; in-game “events” would just roll out based on a player’s local timezone. You’d still need to buy a ticket, but it’d cost $15 instead of $25. The company produced video content players could watch from home as they played along, designed crafts families could make together and created special challenges players around the world could take on together to unlock rewards.

Was it the same? Of course not. While players were free to meet up with friends, they weren’t running around a park with 10,000 strangers. But that’s probably for the better. (I don’t even want to be around 10 strangers right now, much less 10,000.)

Throwing virtual events is hard, but this global GO Fest was a good approximation of the in-person counterpart. Going virtual also meant no park to rent, cell tower overloads to deal with or entrance logistics to get wrong.

It introduced its own challenges (initial technical hiccups led Niantic to host a short “makeup event”) but most players reported a pretty smooth experience. And, virtual or not, it still reportedly brought in millions of dollars for Niantic, 10 million of which it donated to groups in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Cooperative play at a distance

Image Credits: Niantic

Introduced in 2017, “raids” have become a crucial and core component of Pokémon GO. Effectively huge cooperative boss battles, raids are how players earn the chance to catch the game’s biggest/baddest monsters, with up to 20 players meeting up at the same location to work together and take them down.

When new/special Pokémon are released into the raid rotation, it wasn’t uncommon to see packs of dozens of players moving together from raid to raid, coordinating their routes on local Discord groups.

That concept, too, falls apart in a pandemic.

Niantic’s response? Let players raid together even when they’re far apart. In April the company launched “remote raids” — one player still needed to be within reach of the raid location (even if that meant being at home or in their car — they just needed to be close enough that it would appear on their map), but they could invite their far-off friends to assist. As with in-person raids, each player needed a “raid pass,” which cost about a buck unless you happened to be hanging on to one of those that Niantic occasionally gave away for free. It’s still raiding, just … socially distanced. It keeps the physical element of the game intact, without encouraging people to huddle up within coughing distance.

It was a dramatic shift to the way raids worked — but, like most of the other changes, it bent GO’s rules to work within the requirements of this new world. It doesn’t break the game, and, if it ever makes sense to do so, can be reversed without too much trouble.

(It also has the fun side benefit of encouraging players to interact with others around the world; Niantic rolled out a handful of raid Pokémon to only select regions, making it so that catching that Pokémon meant trading friend codes with players thousands of miles away and hoping they eventually beam you into a local battle.)

Giving players more to do on their own

Image Credits: Niantic

From day one, the most progress a player could hit in Pokémon GO was to reach level 40. They’d get there by grinding their way to the top, doing things like catching Pokémon, battling in gyms and sending in-game gifts back and forth to other players.

Reaching level 40 took most players many months (or years) of consistent play. But once they hit it, that was pretty much it. Players keep accumulating XP — some players went many times over what was required to hit level 40 — but it wasn’t good for much except bragging rights. The majority of features Niantic has shipped since launch have focused around getting players to work together, rather than focusing on solo activity.

Earlier this month, that all changed. Seemingly satisfied with the smaller tweaks they’d shipped throughout the year, Niantic was finally ready to launch new content. An update called “GO Beyond” brought a new set of Pokémon for players to catch, a new “season” system that promised to automatically freshen up the game every three months and additional levels. The game’s level cap would now be bumped up to 50.

Adding more levels was a bigger challenge than might be immediately obvious. As I noted, some players — the game’s most dedicated — were far, far beyond what was needed for level 40. Should those players just immediately rocket up to level 50, giving them nothing new to do? Or should the XP requirement for 50 just be so high that no one had hit it yet, putting it out of the reach of 99% of players?

Niantic’s solution is pretty clever: challenges. Players would still get from level 1 to 40 on XP alone; but once there, getting from 41-50 meant needing all of that XP and taking on series of increasingly tough tasks. Challenges like winning hundreds of online player-versus-player battles, walking 200 km with your buddy Pokémon, or catching hundreds of Pokémon in a single day. Every task would take a considerable amount of time, but almost all of them could be tackled alone (or, at least, remotely.) It gave 100% of the player base something to do, without requiring them to do anything unsafe.

The whole thing is an interesting case study in adapting a product without ruining it — in bending all of your game’s rules without breaking the game itself. The company couldn’t do nothing; as it existed at the beginning of this year, it encouraged behaviors that were potentially risky in a midpandemic world.

Niantic couldn’t — or, probably, shouldn’t — just shut down the game; it was the primary pillar supporting a company with hundreds of employees with families to feed. Knee-jerk changes would’ve been easy, but could’ve left the game irreversibly broken. Instead they found a hundred little ways to make it work all while encouraging safer, distanced gameplay.