During my five years with Global Founders Capital, Rocket Internet’s $1 billion VC arm, I saw more than a hundred of Rocket’s incubated companies attempt to internationalize. For background, Rocket Internet has helped launch some very successful businesses internationally, including HelloFresh ($12.9 billion market cap), Lazada ($1 billion exit to Alibaba), Jumia ($3.2 billion market cap), Zalando ($21.2 billion market cap) and many others. Rocket often followed the Blitzscaling model popularized by Reid Hoffman — earning them an appearance in his book of the same name.

After an initial success helping Groupon scale internationally via a merger with Rocket’s incubation firm CityDeal, Rocket’s team have aggressively scaled businesses from Algeria to Zimbabwe — sometimes in a matter of weeks. No surprise, Rocket also has a graveyard of failed companies that were victims of bad internationalization efforts.

Many companies make the costly mistake of launching abroad too soon.

My personal observations on Rocket’s successes and failures start with this crucial point: These learnings might not apply to your unique combination business model, market and timing. No matter how well you prepare and plan your internationalization, in the end you need to be agile, alert and smart as you dip your toes into your first foreign market.

Fail fast and cheaply

Internationalization can be a big driver of growth and consequently enterprise value, which is why investors always push for it. But going abroad can also destroy value just as quickly. As a founder, it’s your job to manage financial and operational risks. Finding the right balance between keeping costs in check and not underinvesting can mean doing things more slowly than your board would like. For example, you might launch new markets sequentially instead of rolling 10 out at the same time.

Adopt a “hire slow, fire fast” mentality for your expansion strategy. Don’t be afraid to pull the plug if things don’t work out.

Our team at Heartcore Capital use the following framework and learnings to guide internationalization strategies for our portfolio companies. A successful internationalization strategy needs to answer and address the “Four Ws”: When, Where, Which and With whom to internationalize. (Regarding the fifth W from journalism, you should not need to ask the “Why” question if you want to build a large business!)

1. When is the right time to start?

Many companies make the costly mistake of launching abroad too soon. They look at internationalization as a detached function, isolated from the rest of the business and then launch their second market prematurely. Follow this simple rule: Wait to internationalize until you hit product/market fit.

How do you know exactly when you’ve reached product/market fit? According to Marc Andreessen, “Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.” He adds that experienced entrepreneurs can usually feel if they’ve reached this point.

Let’s take the man for his word and move on to the actual argument: Until you have product/market fit, you will not be able to distinguish between what you’ve learned from your business model and what you’ve learned from your in-country experience. Mistakes will compound. Complexities and costs will multiply. I contend that insufficient understanding of their business and operating model is the main reason why companies fail with their expansion strategies.

Founders should also consider the underlying costs of internationalizing before they decide to expand (more about this in the “What” section below). Some companies are global by default — think mobile gaming companies — or simply require language localization. Others need to build new warehouses, hire local teams or build entirely new products. The costs and respective risks of expanding prematurely depend heavily on the business model.

There are edge cases where companies need to move quickly to internationalize for strategic reasons — despite uncertainty about their market fit. For instance, companies like Groupon or those engaged in food delivery face winner-takes-most markets, where opportunities for product differentiation are limited. “Blitzscaling” makes sense in cases like these.

However, you should tread carefully if your only reason to start scaling abroad is a large fundraise or to match a competitor’s internationalization efforts. Scaling prematurely for the wrong reasons might just cost you your entire company.

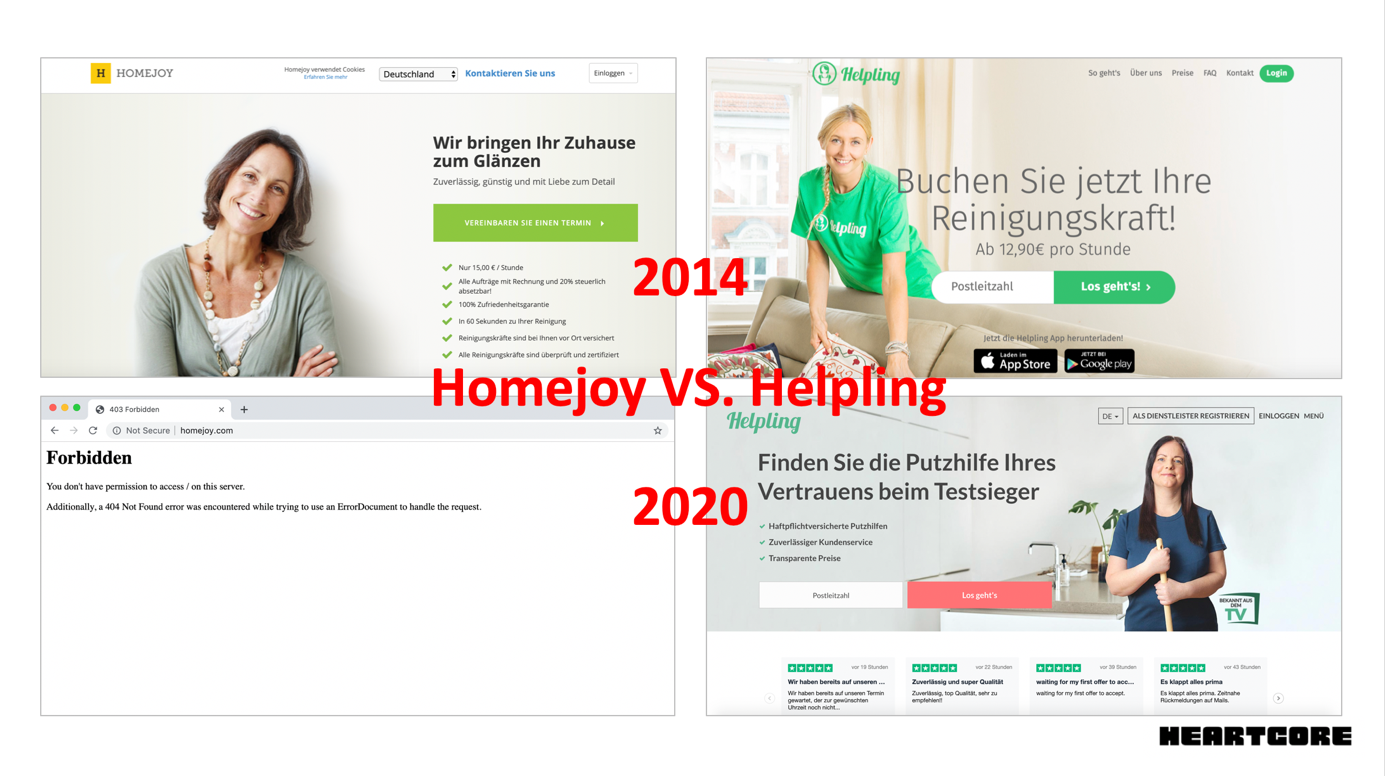

When Rocket Internet announced it would launch the Homejoy model into European markets with Helpling, the American “original” company launched quickly in Germany in an effort to squash their new competitor. In the early days of “on-demand everything,” a managed marketplace for cleaning services sounded like the next unicorn in the making.

In 2013, Homejoy had a fresh $24 million Series A from Google Ventures and First Round — considered a huge round at a time when Instacart had just raised an $8 million Series A and Snapchat had done a $13 million Series A round. It must have seemed like a good idea to squash the German competition early.

As it turned out, Homejoy’s product was not yet ready to scale internationally. Just 13 months after launching in Germany, Homejoy had to cease operations globally, while Rocket’s Helpling is still alive and kicking. Helpling focused carefully on product, automation and making their unit economics work. A rush to crush an international competitor caused the demise of a would-be unicorn.

Homejoy expanded internationally in 2014 in a rush to squash a new German competitor Helpling. Their websites in 2020 show starkly different outcomes. Image Credits: Homejoy/Helpling

2. Where should you internationalize?

When deciding which new international market to tackle, it is vital to do your homework. Analyze the competitive environment, partner availability, infrastructure, culture, regulation and synergies with your home market.

In the early days of e-commerce, it was rather easy to analyze if a market was an expansion target. In the absence of professional competition, Rocket chose new countries based solely on GDP and internet penetration.

At times, Google Street View was the weapon of choice to understand if an emerging country was a good fit. If Foodpanda saw enough restaurant storefronts in the main cities, surely they would see demand for their food delivery marketplace.

Those “good old days” are long gone. Especially in regulated markets and in complex competitive environments — those with numerous competitors and/or substitutes — it is especially important to understand a new market thoroughly before you set up shop.

Build a spreadsheet to rate markets by the market characteristics that facilitate your model or present obstacles. But select carefully for the actual factors that predict a successful market launch — not just the ones for which it’s easy to gather data. You might need to look for nonobvious indicators. For a food-delivery platform like Foodora, GDP or the number of restaurants per capita might not predict a successful launch. Instead, successful expansion might be driven by the availability of riders (predicting rider wage, acquisition cost and retention), labor laws and geographical or meteorological peculiarities.

Talk to other founders and experts about how specific local markets “tick.” You’ll find that subtle cultural differences can render your value proposition less attractive to local consumers. Speaking the local language goes way beyond Google Translate! Many U.S.-based companies struggle with this when they move out of their large, single-language home market. Uber’s botched “Euro Trip” is a prime example: They failed to adapt their public affairs communication strategies to European governmental bodies.

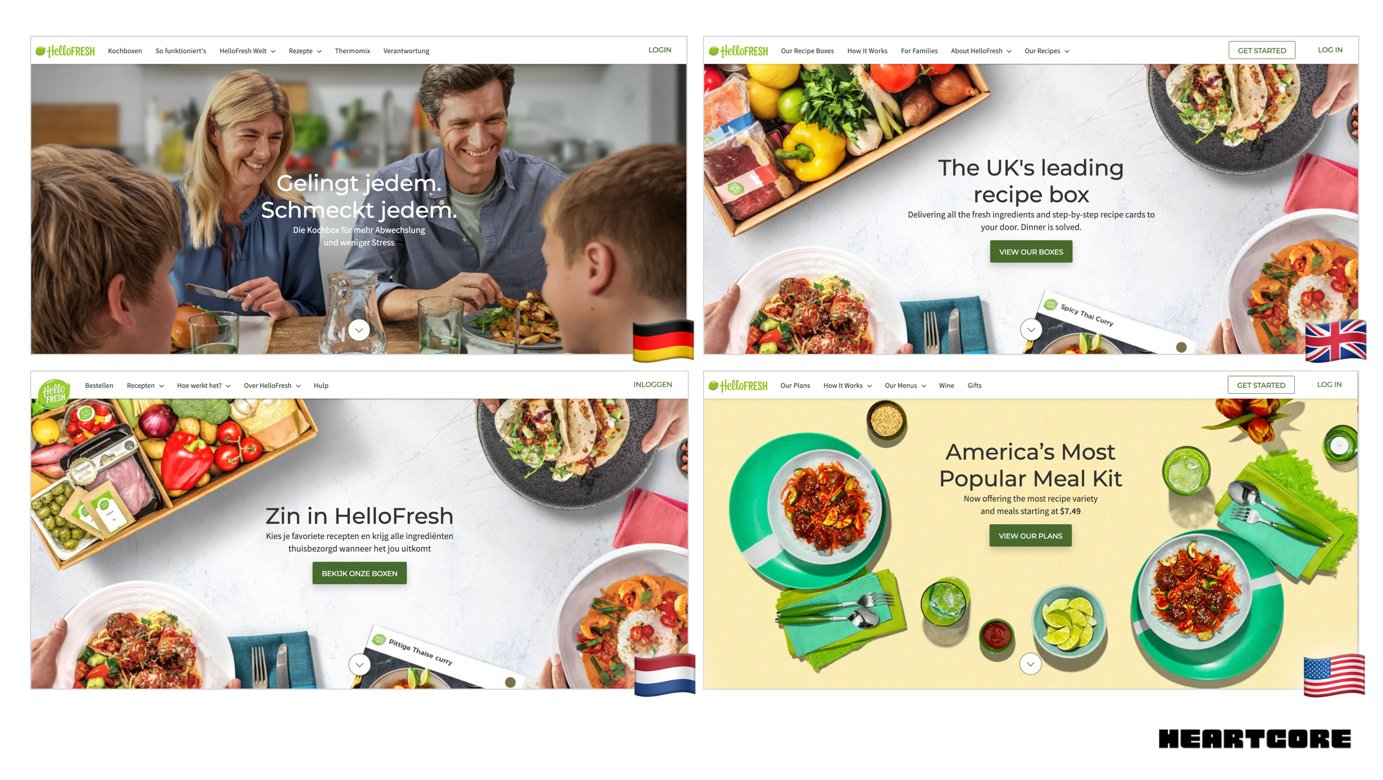

Pictured below, HelloFresh demonstrates their expertise in localizing to each individual market, while maintaining economies of scale in their organization. In addition to adapting their menus to local tastes, they also optimize their calls to action, photos and other content for each country.

Expertly localized landing pages of HelloFresh, suggesting a sophisticated internationalization strategy. Image Credits: HelloFresh

You can test new markets cheaply as part of your research — for example, with a landing page and a Google AdWords campaign. Do you see similar conversion rates, customer acquisition costs, customer support questions and activity metrics as in your home market? If not, investigate if it’s best to stay out of that market and not allocate more resources.

You will also explore strategic considerations when determining if a specific country offers a market fit. Some markets are more valuable than others — perhaps because they are easier to enter or due to the market’s size (revenue potential) or capital market attractiveness. Be aware that your leadership team and board might have different preferences for maximizing enterprise value versus minimizing risk (as in the weighted expected cost of internationalizing).

If you are a CEO or other C-level leader, you will have to optimize between focus and opportunity. How many market launches can your organization endure? Your institutional investors will push you to go faster and higher, while your own organization will push back against change and spreading resources too thin.

3. Which functions should you bring abroad?

As you plan for international expansion, follow one easy rule for resource allocation: You should keep as many functions in your headquarters as possible. Learnings such as process improvements and internationalization core competencies spread much more quickly through a centralized organization. This will make you nimbler, faster and more cost-efficient.

Functions like language localization and marketing are best handled in central offices, while others like partnership sales and distribution, as well as operations are naturally more effective when run in distributed local offices. As a company scales it might allocate an increasing share of their teams abroad. At the very start it is advantageous to keep as many people in the HQ as possible.

Rocket’s companies Lamudi and HelloFresh exemplify what’s possible in regard to efficient centralization. Lamudi, a real estate classifieds site active in South East Asia, kept most business functions in their German headquarters. management, software development and marketing were all kept in Berlin. Only the distribution functions, sales and account management, tasked with onboarding real estate agents, were placed in the respective business region. HelloFresh on the other hand have complex operations and a localized product, hence a large percentage of their staff had to be located in the different countries and regions of operations from the start. Warehousing, picking and packing of their boxes, as well as recipe creation and procurement exist in every country of operation. This should not be surprising, as their product is, well … fresh food. All other functions remained centralized in their Berlin headquarters, while marketing functions were kept centrally at first and were then gradually enforced with local staff to balance speed of global learnings with gaining local insights.

4. With whom should you tackle a new market?

As always when building a large company, the quality of your team matters most. This applies especially to internationalization efforts. Your hiring plans will differ depending on the complexity of the market expansion.

On one end of the spectrum, you can assign functional teams by market and keep them in your HQ — for instance, when only language marketing channels need to be localized. On the other end, one of your founders may move to the new market to provide leadership on the ground. I’ve seen the latter approach work well when European teams expand to the U.S. Because the market is so massive, an expansion often binds so many resources that it presents an existential risk to the company. Senior leadership in market increases the opportunity for success.

For a complex local organization with people and operations on the ground, you will need to hire a country manager. A good country manager is accountable like a manager but is able to think and take ownership like a founder. Highly entrepreneurial people usually do not work well in this role, nor do pure bureaucrats.

Ideally, the country managers have time to work from the HQ for a few months to absorb the company’s culture and then replicate and tailor it to their market. Optimally, you will hire a country manager who shares the cultural background of both headquarters and the new market. You will likely need multiple months to identify, close and onboard a new country head, so you should hire this key resource before you step foot into the new market.

HelloFresh put an interesting spin on the country manager model. Their market expansion model is highly complex, as every country requires new operations and even new products (recipes). They found an effective way to empower their country heads by making each a “co-founder” in their individual market. This contributed to a sense of ownership and gave the manager legitimacy with their sizable local organization and the press.

Build your own playbook

Regardless of the business or industry, every company must develop their own playbook for internationalization. You can and should learn from others’ mistakes and successes. But in the end, your company’s optimal approach to international expansion will have critical differences from others — even from a direct competitor.

The successful portfolio companies at Rocket all got inspired by a peer or competitor, but then blazed their own path to internationalization. They strategically chose between expanding fast or slow, focused on product and kept their organization as concentrated as possible.