Last night Affirm filed to go public, herding yet another unicorn into the end-of-year IPO corral. The consumer installment lending service joins DoorDash and Airbnb in filing recently, as a number of highly valued, venture-backed private companies look to float while the public markets are more interested in growth than profits.

TechCrunch took an initial dive into Affirm’s numbers yesterday, so if you need a broad overview, please head here.

This morning we’re going deeper into the company’s economics, profitability and the impact of COVID-19 on its business. The last element of our investigation involves Peloton and the historical examples of Twilio and Fastly, so it should be fun.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. Read it every morning on Extra Crunch, or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Affirm is a company that TechCrunch has long tracked. I was assigned an interview with founder Max Levchin at Disrupt 2014, giving me a reason to pay extra attention to the company over the last six years. This S-1 has been a long time coming.

But is Affirm another pandemic-fueled company going public on the back of a COVID-19 bump, or are its business prospects more durable?

But is Affirm another pandemic-fueled company going public on the back of a COVID-19 bump, or are its business prospects more durable?

Let’s get into the numbers.

Economics

First, let’s discuss Affirm’s core economics. I want to know three things:

- What does Affirm’s loss rate on consumer loans look like?

- Are its gross margins improving?

- What does the unicorn have to say about contribution profit from its loans business?

These are related questions, as we’ll see.

Starting with loss rates, Affirm thinks it is getting smarter over time, writing in its S-1 that its “expertise in sourcing, aggregating, protecting and analyzing data” provides it with a “core competitive advantage.” Or, more simply, Affirm writes that it has “data advantages that compound over time.”

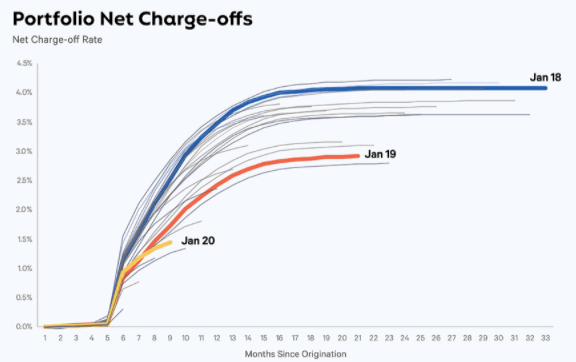

So we should see improving loss rates, yeah? And we do. The company has a very pretty chart up top in its IPO filing that makes its model’s improvement appear staggeringly good over time:

Image Credits: Affirm

But, things aren’t improving as fast inside its results, as Affirm later explains when discussing its aggregate, as opposed to cohort-delineated, results.

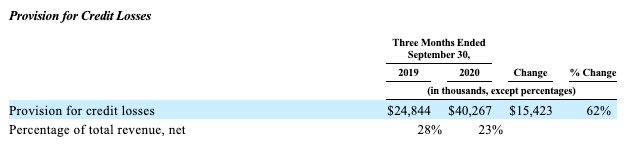

Here’s Affirm discussing its provision for credit losses in its most recent quarter (calendar Q3 2020) and the period’s year-ago analog (calendar Q3 2019):

Image Credits: Affirm

As we can see, the percentage of total revenue that Affirm has to provision for expected credit losses is going down over time. That’s what you’d hope to see.

To better explain what’s going on, let’s explore what Affirm means by “provision for credit losses.” Affirm defines the metric as “the amount of expense required to maintain the allowance of credit losses on our balance sheet [that] represents management’s estimate of future losses,” which is “determined by the change in estimates for future losses and the net charge offs incurred in the period.”

And it got quite a lot better in the last year, which the company says was “driven by lower credit losses and improved credit quality of the portfolio.” So, Affirm is getting better at lending as time goes along. What does that mean for its gross margins?

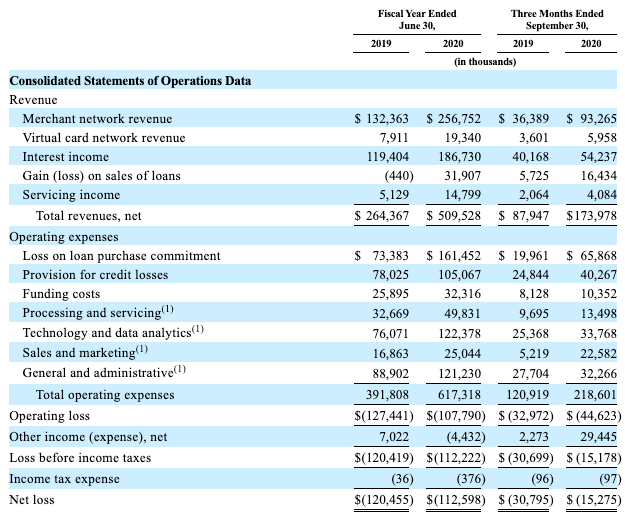

Well, Affirm doesn’t provide direct gross margin results. So we’re left to do the work ourselves. For reference, this is the income statement we’re working off of:

Image Credits: Affirm

Fun, right? Annoying, but fun.

How should we calculate the company’s gross margins? We can’t drill down on a per-product basis given that costs aren’t apportioned in a manner that would allow us to, so we’ll have to take Affirm’s revenue as a bloc, and its costs as a bloc as well.

Which lines on the expenses list would we consider a cost of revenue, and thus part of our gross margin calculation? The first thing we have to ask is what “loss on loan purchase commitment” means. It’s a bit technical, but here’s the core riff from Affirm, inside of which I have bolded the key words:

In addition, there are certain timing differences in the recognition of certain revenues and expenses associated with our relationship with our originating bank partner that do not reflect the unit economics of transactions processed by our platform in the period presented. We purchase loans from our originating bank partner that are processed through our platform and our originating bank partner puts back to us. Under the terms of the agreement with our originating bank partner, we are generally required to pay the principal amount plus accrued interest for such loans. In certain instances, our originating bank partner may originate loans with zero or below market interest rates. In these instances, we may be required to purchase the loan for a price in excess of the fair market value of such loans, which results in a loss. We recognize these losses as loss on loan purchase commitment in our consolidated statements of operations. For the periods presented, references to our originating bank partner are to Cross River Bank.

In short, Affirm has some loans that come with no interest; it has to buy those back from its “originating bank partner,” and since they yield zero, and Affirm is buying the debt, it winds up technically overpaying for the instrument. So, it books a loss on the transaction.

In short: This is definitely a cost of revenue. So it counts against gross margin.

What about Affirm’s provision for credit losses? That’s a cost of revenue, we reckon, as it is derived from the core generative effort of the company.

Next, what about funding costs? Per Affirm, those are “the interest expense we incur on our borrowings, and amortization of fees and other costs incurred in connection with our funding,” so we’d call that a cost of revenue as well.

The last one is tricky. What about “processing and servicing”? According to Affirm, that line item is this:

Processing and servicing expense consists primarily of payment processing fees, third-party customer support, and collection expenses. Additional expenses include salaries and personnel-related costs of our customer care team, and allocated overhead.

Some of that sounds like a cost of revenue, something that would land on the negative side of gross margin. But not all of it, by our early-morning read. So we’re a bit stuck.

How should we calculate Affirm’s gross margins, then? Affirm doesn’t try. Instead it ties up all the expense categories that we just discussed, adds in a few more and calls the result contribution margin. That contribution margin, when applied to the company’s revenue yields contribution profit.

What’s that? Affirm defines contribution profit as follows:

[T]otal revenue less the following direct costs that are closely correlated to and variable with the generation of that revenue: (i) the amortization of discount, which is included in our GAAP interest income; (ii) the unamortized discount released on loans sold to third-party loan buyers; (iii) provision for credit losses; (iv) funding costs; and (v) processing and servicing expense.

You can see our gross-margin included expenses in there toward the end, so this contribution is gross-margin related.

But what about that stuff up front, the amortization bits? It’s more complicated than we can get into this morning.

But if you take our revenue costs, deducting further to include the aforementioned amortization items, you get contribution profit at the end. Which, when divided by revenue would give you contribution margin, a gross-margin cognate of sorts.

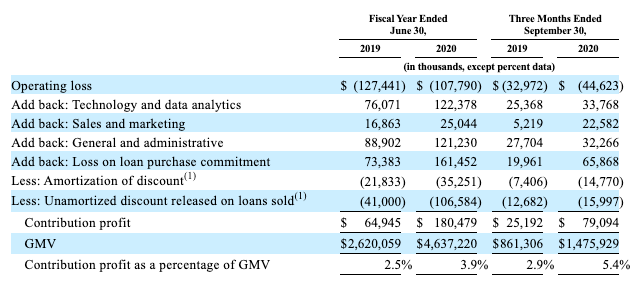

Want to see that in practice? Observe how Affirm explains the different pieces in the contribution calculation, when it explains how to convert operating losses — a standard GAAP metric — to contribution profit, or what we’re somewhat considering to be Affirm’s gross profit:

Image Credits: Affirm

Fun, right?

What matters most, in case that chart wasn’t much help, is that bottom line of numbers. What portion of Affirm’s gross merchandize volume (GMV) distills into contribution profit? A growing percentage. Indeed, in its fiscal year ending June 30, 2019, it was 2.5%. That more than doubled by the calendar third-quarter of 2020, when the metric rose to 5.4%. That’s a huge improvement.

So, Affirm is increasingly able to turn consumer platform spend (GMV) into revenues and then into post-expenses contribution profits. That’s what you would hope to see if its economics were improving.

We’re now ready to talk profits.

Profitability

Working from where we left off, what impact has Affirm’s rising contribution margin — as we’re using contribution margin as something akin to a comp for gross margin, contribution profit is akin to gross profit for our purposes — had on its overall profitability?

Our guess is that rising contribution margins boosted contribution profit, which in turn has helped limit the company’s GAAP losses. This is correct, as we can see by looking at both quarters:

- Calendar Q3 2019 contribution margin: 2.9%.

- Calendar Q3 2019 contribution profit: $25.2 million.

- Calendar Q3 2019 revenue: $87.9 million.

- Calendar Q3 2019 net losses as a percentage of its revenue: 35%.

Now, let’s run the same math with calendar Q3 2020, which had better economics (contribution margin) and more revenues from which to derive contribution profit:

- Calendar Q4 2020 contribution margin: 5.4%.

- Calendar Q4 2020 contribution profit: $79.1 million.

- Calendar Q4 2020 revenue: $174 million.

- Calendar Q4 2020 net losses as a percentage of its revenue: 8.8%.

Why did we do all of that? Isn’t it blindingly obvious that if Affirm were racking up contribution margin (gross margin) improvements and revenues were rising, net margins would improve? No. Never presume operating leverage in a unicorn. It must be proven.

We can now trace the rapid improvement of Affirm’s net margins back to its growth (GMV, revenue) and improving economics. By working through all those numbers we have earned a better feel for how Affirm has matured over time.

Though, as we will show shortly, it has had a bit of a boost along the way.

COVID-19 and revenue concentration

Affirm has a Peloton problem — and it has enjoyed a Peloton boom. As Peloton itself has grown, it constitutes a larger share of Affirm’s revenues:

Our top merchant partner, Peloton, represented approximately 28% of our total revenue for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020 and 30% of our total revenue for the three months ended September 30, 2020. Our top ten merchants in the aggregate represented approximately 35% of our total revenue for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020 and approximately 37% of our total revenue for the three months ended September 30, 2020.

What’s going on? A lot of folks bought Pelotons as the pandemic closed gyms, and many customers used Affirm to finance their purchase.

Notably the unicorn’s next nine largest customers are worth just 7% of its revenue, meaning that Affirm really has a singular-company risk; if Peloton drops Affirm, or sees its own sales slow, our fintech startup could be sharply undercut.

Why worry about the possibility? Because investors have a few recent examples of tech companies going public on the back of attractive growth, only to lose a single, key customer, blowing a hole in their ability to grow.

It happened to Twilio regarding Uber (more here), and it happened to Fastly and its customer TikTok even more recently (more here). Revenue concentration is a legitimate risk. And it’s something that Affirm will have to talk its way through during its roadshow.

It doesn’t help that the percentage of its revenue that Peloton accounted for rose in the September 30, 2020 quarter from the prior fiscal year; it’s harder to downplay a risk when the underlying factor of that risk is strengthening.

COVID-19, which has been a huge benefactor of Peloton has also boosted e-commerce in general, helping Affirm — which facilitates online transactions — grow. But the pandemic has had an uneven impact on its revenues:

For example, following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, our revenue from merchant partners in the travel, hospitality, and entertainment industries declined, but we saw a significant increase in revenue from merchant partners offering home fitness equipment, home office products, and home furnishings, though we may see potential downswing in these categories if the trends we have seen thus far in the COVID-19 pandemic reverse

I would read that as net positive for Affirm. So, COVID-19 is probably more of a risk if it leaves quickly than if it lingers, from Affirm’s growth perspective.

Not to be too macabre during a global catastrophe, but current trends make it clear that e-commerce isn’t going to slow down. Which means Affirm is probably going to enjoy more quarters of boosted growth, partially spun by Peloton’s wheels.

A quick recap

We’re approaching 2,200 words now — if you are still reading, it means my editors decided against killing me, so let’s quickly summarize:

- Affirm’s economics are improving over time, though we lack some of our more traditional metrics from which to measure.

- Profitability is improving as its economics mature, which isn’t a surprise. However, inside its growth and polished economics is one huge customer and a pandemic-led tailwind.

- It’s impossible to read Affirm’s S-1 without the pandemic in mind; how investors weigh the eventual end of COVID-19 and the return to normal life for Affirm’s business will help set its valuation, and thus its revenue multiple.

Got all that?