Algorithms are reshaping many parts of our lives, including how news gets to us. Around the world, entrepreneurs make use of algorithms to program their ideal news apps, and while they normally agree on universal objectives like fighting fake news, their views diverge elsewhere, leading to different applications of machines and user experiences.

No one has a monopoly over the “right” approach to build an algorithmic news app, but it’s perhaps timely and necessary to examine various players in the field and ask how their black boxes affect people’s content consumption. We need look no further than China and the U.S., where machine-driven news platforms are in full bloom.

Show me more of what I want

Before ByteDance became synonymous with TikTok globally, it was known in China for its algorithm-powered news app Jinri Toutiao, or Today’s Headlines. The Chinese app has not disclosed its user numbers for years, but third-party data suggests it had 360 million monthly active users by January 2020, eight years after launching.

Zhang Yiming, the founder of ByteDance, built Toutiao with the goal to give users more of what they want.

“We pictured Toutiao’s feed to be a smart antenna linked to an infinite ocean of information. When you swipe, you retrieve what you’re most interested in right now and in this place,” said Zhang at the company’s seventh anniversary. His remark echoes the app’s catchy tagline: Only what you care are headlines.

To achieve its mission, the app predicts user preferences based on a few parameters, Toutiao’s scientist Cao Huanhuan revealed in a speech in 2018: profiles per the app’s understanding of user demographics; content’s timeliness and popularity; users’ locations; and what similar users like to consume. The app then measures the success of its recommendations by tracking clicks, time spent, likes, comments and shares.

Having world-class algorithms is just part of the story; the other challenge is to create Zhang’s “ocean of information.” Early on, Toutiao relied on crawling the internet to fill its reservoir; these days, the app runs a publishing platform with creators ranging from news outlets, bloggers, celebrities, through to influencers. To sustain the torrent of information available, the app doles out subsidies and devises monetization methods for creators, sharing ad revenue and allowing them to sell products.

Image Credits: Toutiao (opens in a new window)

Like some Western media giants, Toutiao’s main revenue driver is advertising, meaning it’s incentivized to lock users inside the app for as long as possible. A common criticism of Toutiao’s engagement-centric approach is it gives rise to “information cocoons,” a concept similar to what’s better known in the West as “filter bubbles.” Both describe the emergence of a highly personalized online environment in which people see only a selective dose of content they like. The app’s current chief executive Zhu Jiawen, who worked on the app’s algorithms, believed the product does the opposite.

“To solve the information cocoon problem, a comprehensive information app is, what I think, the most effective solution. Only when there are enough forms of content and methods of distribution can people see a bigger world,” the CEO said at an event in 2019.

By “comprehensive,” Zhu was referring to the “superapp” state Toutiao had reached. Today, the service not only recommends content but also allows users to subscribe to publishers and search for content. In Zhu’s view, information cocoons can be tackled by the part of algorithms that shows user A what user B, someone similar to user A, likes to read. Two users who share similar demographics may end up liking vastly different things.

Show me what’s important

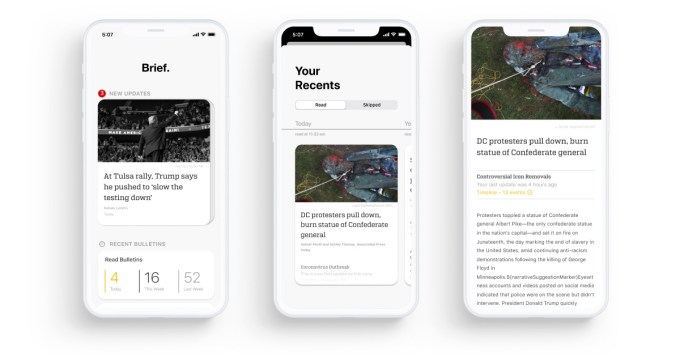

Toutiao may be great for discovering new interests. Other entrepreneurs, on the contrary, want users to focus on just the “important” news of the day. Brief is such an example.

The app, co-founded by former Google engineer Nick Hobbs, is the antithesis of Toutiao, serving up only news that “matters” rather than “interests” people. In that regard, the app is more akin to a traditional newsroom relying on trained journalists to pick and edit news, while users pay a subscription fee. The staff summarizes the facts of the news in bullet points, along with a timeline of events and viewpoints from all sides. The app also limits the number of news items to five to eight per day, with the aim to reduce information overload.

Machine intelligence does play a big part in Brief. Instead of performing the job of curation and recommendation, algorithms provide a tool for Brief’s journalists to organize and present information in a highly digestible way. For instance, when news breaks and develops rapidly, some readers will want to follow it obsessively throughout the day, while others just want a post-facto rundown the next day.

“Our technology allows our editors to create both of those experiences,” explained Hobbs. “For the person who’s coming along, they get a live blog with just the latest update. For somebody who comes around later, all of that information has been summarized and condensed.”

The focus on perceived “quality” over quantity of news unsurprisingly results in Brief’s streamlined design, a contrast to Toutiao’s cluttered interface with an infinite stream of addictive content.

Image Credits: Brief

The obvious flaw of Brief is that it’s prone to selection bias amongst its journalists. Hobbs admitted, “whether you’re using technology or an editorial process, bias will creep in.”

“That’s because algorithms are made by humans. The data we select to train algorithms are selected by humans. The raters that score data in order to train algorithms are obviously humans.”

The startup’s way to maintain objectivity is three-pronged. It starts by evaluating the ideological predispositions of an array of mainstream news sources. When something is particularly partisan, polarized or prone to bias, the news gets reviewed by multiple sets of eyes within the newsroom. The last step is to listen closely to readers by letting them easily message the editors.

Though Hobbs declined to disclose Brief’s user number, he said more than 40% of the users who tried the app ended up paying for its subscription.

Show me what I disagree with, too

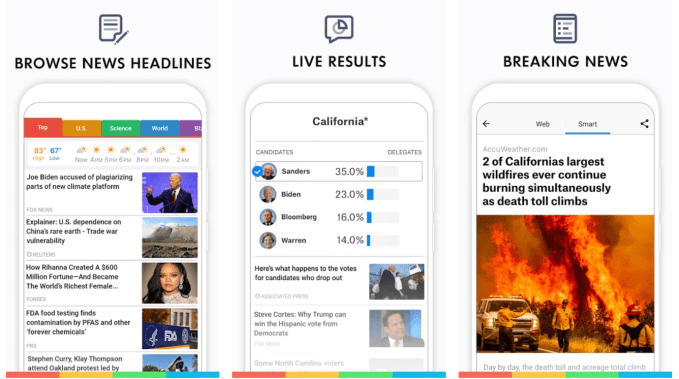

SmartNews, an app that originates from Japan and has gained a substantial user base in the U.S., shares similarities with both Toutiao and Brief. Like Toutiao, SmartNews personalizes content, uses recommendation algorithms and focuses on user engagement. But like Brief, it’s not obsessed with showing readers what they want to see and deliberately includes perspectives with which they may disagree.

“Personalization is an incredibly powerful thing, but excessive personalization is an incredibly limiting thing,” suggested Rich Jaroslovsky, who managed the online edition of The Wall Street Journal before joining SmartNews as its vice president for content and chief journalist.

The app, which boasts 20 million global monthly active users, achieves high engagement metrics precisely because it delivers “a broad variety of content and a broad variety of perspectives,” he said.

When a political story triggers a significant amount of content and a range of opinions, SmartNews adds a “news slider” to the subject that users can slide along to view analysis and various perspectives.

“We’re not forcing people to consume it,” said Jaroslovsky. “I think when people are in a filter bubble, even if that filter bubble is very comfortable, a lot of people have this nagging feeling that there’s more out there. And they’re right, there is more out there.”

Image Credits: SmartNews (opens in a new window)

Humans and machines are complementary at SmartNews. The job of human staff is to make the algorithm “journalistically smarter.” The machines, in turn, analyze, categorize and recommend content, while the staff continues to improve the algorithms. For example, when the staff detect click baits or stories without much original information, they create training sets for finetuning the algorithms.

There are many other news apps out there that make use of algorithms, including the numerous followers that Toutiao inspired in China, giants Google News and Apple News, emerging player NewsBreak that aspires to reinvigorate local news, not to mention nascent bootstrapped projects like QuickNews, started by a former Amazon engineer who believes in getting news in “real-time.” There are also Facebook, Twitter and Youtube, of course, many people’s go-to news platforms.

Consumers will gravitate toward the algorithmic solutions that suit them. The burden is then on companies to be accountable for the tools they have created, instead of delegating that responsibility to machines.

“What I’ve seen over 25 years is computers have gotten a lot better at doing some of the things that they couldn’t do 25 years ago. That just frees the humans up to move up the value chain and to do even more important work,” Jaroslovsky remarked. “But at the end of the day, technology is a tool like any other tool. It depends on how it’s used by the people that are wielding the tool.”