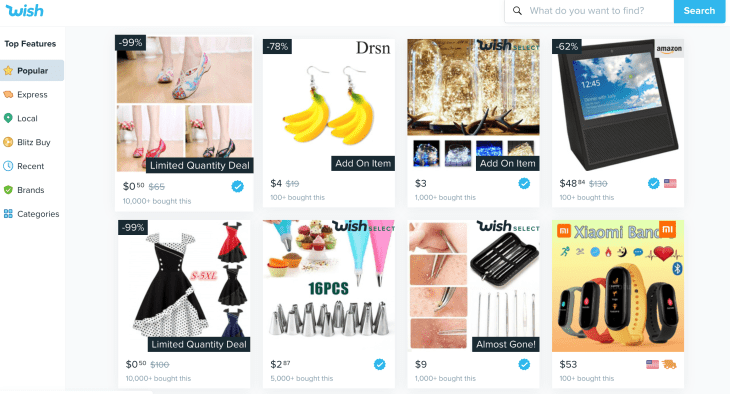

Wish, the San Francisco-based, 750-person e-commerce app that sells deeply discounted goods that you definitely don’t need but might buy anyway when priced so low — think pool floats, guinea pig harnesses, Apple Watch knockoffs — said yesterday that it has submitted a draft registration to the SEC for an IPO.

Because it filed confidentially, we can’t get a look at its financials just yet; we only know that its investors, who’ve provided the company with $1.6 billion across the years, think the company was worth $11.2 billion as of last summer, when it closed its most recent financing (a $300 million Series H round). Meanwhile, Wish itself says it has more than 70 million active users across more than 100 countries and 40 languages.

The big question, of course, is whether the now 10-year-old company can maintain or even accelerate its momentum.

It’s not a no-brainer. On the one hand, it’s a victim of the increasingly chilly relations between the U.S. and China, from where the bulk of Wish’s goods come. Then again, Wish has been beefing up its business elsewhere in the world partly as a result of the countries’ shifting stance toward one another.

For example, it told Recode last year that it’s increasingly looking to Latin American markets — Mexico, Argentina, Chile — for growth, and that it’s planning a bigger push into Africa, where it’s already available in South Africa, Ghana and Nigeria, among other countries.

Wish has always been a work in progress. It was co-founded by CEO Peter Szulczewski, a computer scientist who previously spent six years at Google before co-founding a company call ContextLogic, from which Wish evolved. The idea was to build a next-generation, mobile ad network to compete with Google’s AdSense network, but Szulczewski and his co-founder, Danny Zhang, realized they were “pretty bad at business development,” as he once said at an event hosted by this editor, so eventually they pivoted to Wish.

Wish originally asked people to create wish lists, then the company approached merchants, letting them know a certain number of customers wanted, say, a certain type of table. It was smart to recognize that showing the right recommendations to shoppers would become critical to its users, though it didn’t necessarily foresee the types of merchants it would ultimately work with, most of them in China, Indonesia and elsewhere in East Asia and Southeast Asia who are focused on value-conscious customers. As Wish quickly realized, these merchants didn’t have other ways to sell to or communicate with customers elsewhere in the world, so they didn’t mind paying Wish a 15% take to handle this for them.

Wish also focused around lightweight items that it could ship cheaply from China — if slowly — using something called ePacket. It’s a shipping option agreement that was established nine years ago with the cooperation of the U.S. Postal Service and Hong Kong Post (and later made available to 40 countries altogether) that enables products coming from China and Hong Kong to be sent at rock-bottom prices as long as they meet certain criteria — they don’t weigh too much, they aren’t worth too much, they adhere to certain minimum and maximums regarding their size, and so forth.

The mix has proved powerful for Wish, despite growing competition from China-based outfits like AliExpress that offer many of the same goods to the same customers around the world. (Wish has also competed, always, with Walmart and Amazon.)

The company has also soldiered on despite apparent struggles to keep customers coming over time. Because it doesn’t sell essential items but rather a grab bag of different items, people tend to cycle out of the app after a few months of their first visit, as The Information once reported.

A bigger issue now is that, as of two months ago, a new USPS pricing structure went into effect that raises rates on international shipments. It also requires foreign recipient countries to ratify new rates under ePacket (whose recipient countries, by the way, have been downsized from 40 to 12). That means that companies like Wish either have to pay more to ship their goods — forcing its vendors to charge more — or move to commercial networks.

Of course, a third option — and one that may position Wish well for the future — would be for Wish to invest in more local warehousing in the U.S., Europe and others of its growing markets, which it told Recode that it is doing, along with seeking more local vendors near its biggest markets.

Given shifts in the way that commercial real estate is being used — with retail-to-industrial property conversions accelerating, driven by the growth of e-commerce — it’s probably as good a time as any for Wish to be making these moves. Whether they are enough to sustain and grow the company is something that only time can answer.

Again, we’ll collectively know much more when we can get a look at that filing. It should make for interesting reading.

Wish’s private investors include General Atlantic, GGV Capital, Founders Fund, Formation 8, Temasek Holdings and DST Global, among others.