Once upon a time, fintech founders could pitch 10 investors before closing a round in a relatively hushed way. Entrepreneurs could even ask VCs to sign nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) to keep their information confidential. Today, everyone is a fintech investor and no one signs NDAs.

This changed dynamic puts founders in a difficult position.

Nabeel Alamgir, CEO and founder of Lunchbox, struggled to raise his first institutional check for his restaurant tech startup. After searching for more than a year, Alamgir found an investor who understood his vision. Better yet, the investor had connections to restaurants in New York City that Alamgir wanted to land. So, Alamgir shared everything about Lunchbox, from the financials, to the product integration road map and go-to-market strategy.

After a month of due diligence, the investor ghosted Alamgir. Four months later, that same investor’s portfolio company launched a product mimicking Lunchbox.

“I did not do due diligence on them as they were doing on me,” he said. “And I forgot all my rules. Most rules go out the window as cash is running out.”

Alamgir’s experience is a classic case of back-channeling, a sometimes unfortunate yet uncommon occurrence for founders in Silicon Valley. It’s not a secret that investors share intel with each other as a competitive advantage; but as venture capital grows as an asset class and more investors break into the industry, the way information disseminates will become even more elusive and broad.

Alamgir advises early-stage founders who are looking to raise their first check to “contain excitement.”

“When you talk to an investor you have to go out and be measured because most likely the person you talked to will say ‘no,’” Alamgir said. “It is your job to convince them, but it is also your job to keep as much information close to the chest until you progress into multiple meetings.”

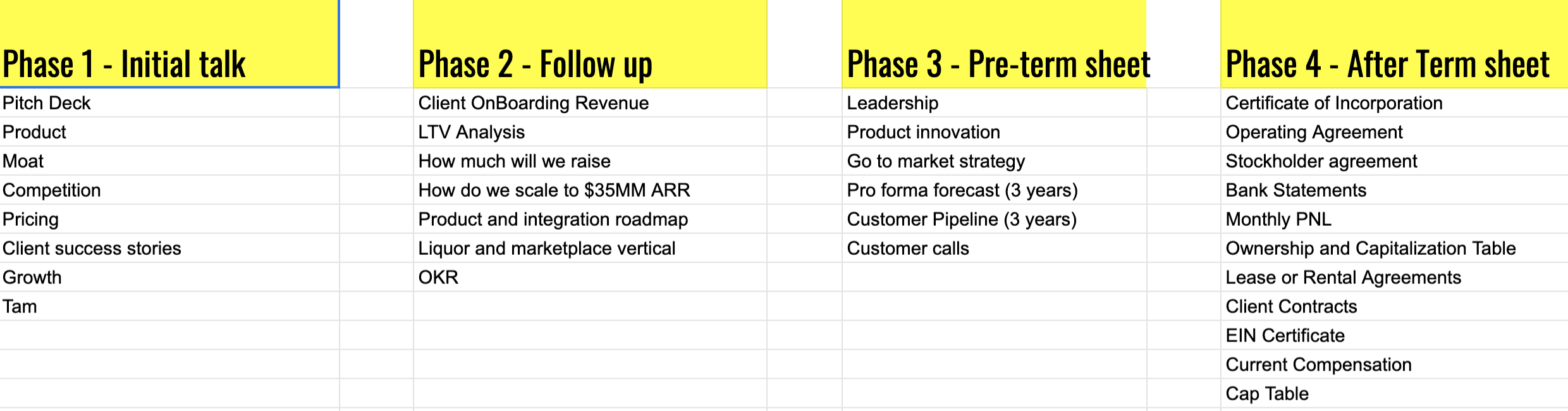

He broke out the first-check fundraising process into four buckets: initial talk, follow up, pre-term sheet and post-term sheet.

Image Credits: Nabeel Alamgir, founder of Lunchbox.

The system is more complex than obvious red flags. One example: Partners at Andreessen Horowtiz invest in microfunds to stay ahead of early-stage trends. In other words, even if your investor isn’t invested in a competitor, their investor (or limited partner/LP) might be. Once you start fundraising, there is no way to stop venture capitalists from sharing information with each other.

Walzay founder Humaira Khan said she has never asked anyone to sign an NDA but added that she is still paranoid about sending too many details about her talent marketplace startup to potential investors. Similar to Alamgir, she has been in contact with investors who gathered details about her user acquisition and business model before launching a competing product.

Sach Chitnis, a co-founder and general partner of Jump Capital, has seen investors change the way they approach conflicts of interest since he started in 2012. Startups are often born off of trends, which means dozens of competing startups may emerge at once in a single sector.

“Once there’s a trend, you’ll have three to four companies all looking to raise a Series A, B or C at the exact same time for the exact same space,” he said.

Any thorough investors will talk to multiple companies within a category it is interested in, but the difference comes when you look at how an investor communicates its intent with a founder.

Chitnis said Jump will pick a category to invest in before selecting a handful of startups to meet with, taking on a “hunting versus gathering” approach. Then, the lead partner on the deal tells any startup they meet with who else is in the running.

“Proactively, we tell every single one of them that we believe this is a segment we want to invest in, here is who else we are talking to, and one of you will get a $5 to $10 million check,” Chitnis said.

Transparency like this can introduce a competitive dynamic, but Chitnis said it has usually been met with eagerness because it shows entrepreneurs that his firm has an appetite and an understanding of the sector in question.

Sometimes, however, conflicts of interest are inevitable.

For example, in a 2019 interview, Finix described itself as shaking “up the lucrative but static payments industry but in a very un-Stripe-like way.” One year later, top-shelf investor Sequoia backed out of its Finix investment because it was too similar to Stripe, another one of its portfolio companies.

It remains somewhat of a mystery on how Sequoia, which likely does countless hours of due diligence on any investment it makes, missed the conflict between two startups that both help other businesses bring on payments. (Finix CEO Richie Serna did not respond to a request for comment.)

As the lines continue to blur, founders should continue to be careful with key information and investors should work to be transparent in their intentions.