One of the big challenges (among many) with the coronavirus pandemic is that overwhelmed health services do not always know how best to deploy the limited resources they have to meet the demand of people falling ill with COVID-19. For example, we know that more ventilators and beds will be needed, but where specifically are the outbreaks happening and how can those local areas be served better?

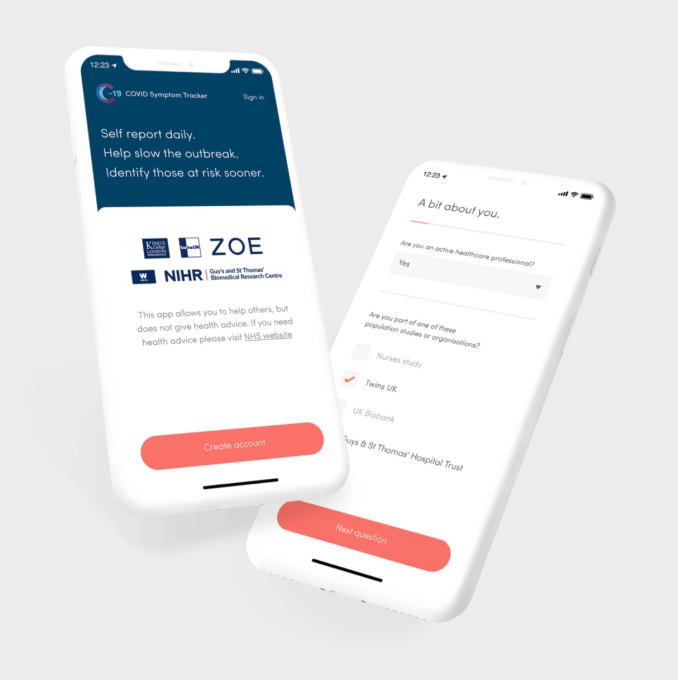

Now, an app in the U.K. called the C-19 COVID Symptom Tracker, developed out of an unlikely corner of medical research — looking into the progression of medical conditions by tracking twins — is asking people to self-report their symptoms in an effort to start to gather more of that detail.

In line with how the public is trying to step up its efforts to get involved in the fight to contain the disease (some 405,000 people have also volunteered to help the NHS deliver medicine and other supplies to quarantined people, and help people home from the hospital) the Covid-19 app has itself gone viral, with 750,000 downloads since being launched on Tuesday morning. The app now is the third most popular app overall in the UK on the Apple App Store, and the number-one in the medical category, according to figures from App Annie.

Developed by a startup called Zoe in partnership with researchers at Kings College Hospital in London, the plan is to bring the app next to the U.S., where the latter group had already been working with colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital and Stanford on a previous project (more on that below).

To be very clear, the app itself is not a diagnostic tool — these are being developed on a national level, linking people through to local services. Nor is it designed to give the public any clarity on where COVID-19 symptoms are cropping up. (As we reported earlier, there are a number of those being built and used already, too, providing maps and other data.)

Instead, it’s a research app designed to bring together information that could be useful to medical professionals to better plan their responses.

At first, the plan was to build an app to figure out where there were clusters of cases in order to better determine where testing kits, in short supply, might be better allocated.

“We were actively speaking to a multitude of companies that are making or have testing kits, and originally the idea was that if we identified people who were expressing symptoms, maybe we could get a testing kit to them faster,” said Sara Gordon, a spokesperson for the company. That proved to be too difficult, she added, because the testing arena is very fragmented and so it’s not clear whether they all reliably and consistently work the same (and work well).

Then, attention turned to where the data could be useful, and providing support to the NHS, the U.K.’s National Health Service, in determining the shape and evolution of the virus, in order to research it better and figure out how to deploy NHS resources, was where the team landed.

The ExCel conference center in the Docklands in East London is being set up as a field hospital now, “but there are many other places that will need hospitals opened,” she said, “and this could help figure out where.”

The app has a somewhat unlikely origin. It was created by Zoe, a spin-out from Kings College Hospital that is now backed by some $27 million in funding — investors include Daphni in France and Accomplice (formerly Atlas Venture) in Boston, among others — in partnership with a research group at Kings College that has been tracking twins.

“We’re a healthcare startup that has been running the world’s largest nutrition study,” Gordon said, spanning some 25 years (predating the startup materialising or getting spun out) and 8,000 groups of twins, and covering not just people through Kings, but also Stanford and Mass General.

Researching food intake as well as blood and stool samples, the idea was to “understand everything about how genes determine how we metabolise food, our immune responses, and more,” using twins with nearly identical DNA to do this, and using that input to determine new insights into cardiovascular disease, diabetes and other chronic conditions.

Last week, Zoe’s co-founder, Tim Spector, who is also Professor of Genetic Epidemiology at King’s College London and director of the Twins UK study, spoke to the Zoe team about creating an app to reach out to the 8,000 twins in the study (who had already been using Zoe to track other parts of their lifestyles) to see how many of them were expressing signs of the novel coronavirus. It could have been a useful test pool also for determining what role age plays in this, as the long-term study means many of the people involved are older.

Events overtook those plans, too:

“From the conversations we were having with Kings” — the inner-city hospital (which happens to be my local hospital) has been very much at the front lines of the coronavirus response in London and the U.K. — “we decided that if we’re making this available to twins, maybe we should open it up to more people,” Gordon said. “One of the main issues here in the U.K. and other countries has been that governments haven’t been able to get good enough data about where the virus is spreading or how bad symptoms are.”

There are some major caveats with the app, which it seems are still a work in progress.

The biggest of these is that the app itself is self-reporting. That means that you are putting a lot of trust into people to be accurate and also consistent with each other in how they are describing their symptoms. (Is my idea of a continuous, unproductive cough the same as yours? And are our coughs even a reliable enough indicator of what is going on?)

“We’re relying on the public to be honest about their symptoms,” Gordon said more than once during my conversation with her. That would have been one reason too why tying the surveys to testing kits (the original idea) might have been problematic: so many people want some assurance that I’m guessing a lot would have reported just to get the kits.

The other is that it requires regular, habitual use: a person reporting one day is only really useful if that person reports for the rest of the days subsequent to that to get a picture of how and if symptoms progress. On the other hand, that could be a boost to self-reporting too: even if my version of a continuous cough is different from yours, at least I’ll now be showing how and if anything else gets added to that cough over time.

“What we’re trying to do is scale what we see and what scientists are classifying as severity of symptoms,” she said. “If someone has fever over a certain period, then that’s logged as red. Amber is feeling ill.”

Over the next few days she said the team is hoping to separate COVID-19 symptoms apart from those associated with a common cold. “We’re working to make sure that in reporting we’re being able to divide which are common cold or flu and which are COVID-19.”

A third issue is the data usage on the app. The privacy terms on Zoe note that the data is only there to be used by the researchers, but it also notes that it could travel outside of the EU not just for analytics but to be shared with other research partners.

Indeed, privacy experts and others are still debating the implications of how crowdsourced services like this one, built quickly for the crisis, are really walking a grey line when it comes to questions of privacy and data protection. For now, Zoe defends its position.

“The data policy we have is the one we have had legal advice on,” Gordon said. “It’s compliant with GDPR, and if and when we pass to others, people’s names are anonymised and switched to code. We feel we have super-strict data rules on our side.” She added that the compliance in the U.S. is even more strict because any research they do there has to go through a clinical process to make sure it is protected, “so there should be absolutely no concerns about data privacy.”

All the same, even with all the best intentions, there could also be a risk of your data getting misappropriated when handed off from one party to another and no longer under local jurisdictions.

That skepticism is possibly not helped by the fact that the co-founder and CEO of Zoe, Jonathan Wolf, is the former chief product officer of Criteo, the adtech company that happens to be getting investigated by France’s data protection watchdog for how it uses personal data (Wolf left the firm in 2016 before co-founding Zoe in 2017). Criteo is described simply as a “machine learning company” — no mention of advertising — in Wolf’s bio on the Zoe site.

(The third co-founder is George Hadjigeorgiou, who also doesn’t have any direct links to the medical industry, having been the CEO of HouseTrip and the co-founder of efood, a delivery startup.)

On a more positive note — and there is a lot to see that is positive here — Zoe itself is a business, but this project specifically was built without that in mind.

“Building this to meet the current need was just a decision we made,” Gordon said. “The team switched from the commercial product to this for the next few weeks, and the plan is to make it open source and to hand it off to the right people eventually. We just want to get the ball rolling.”

Remember to stay two meters apart from others when you go out, and stay at home when you can. Keep well, TC readers.