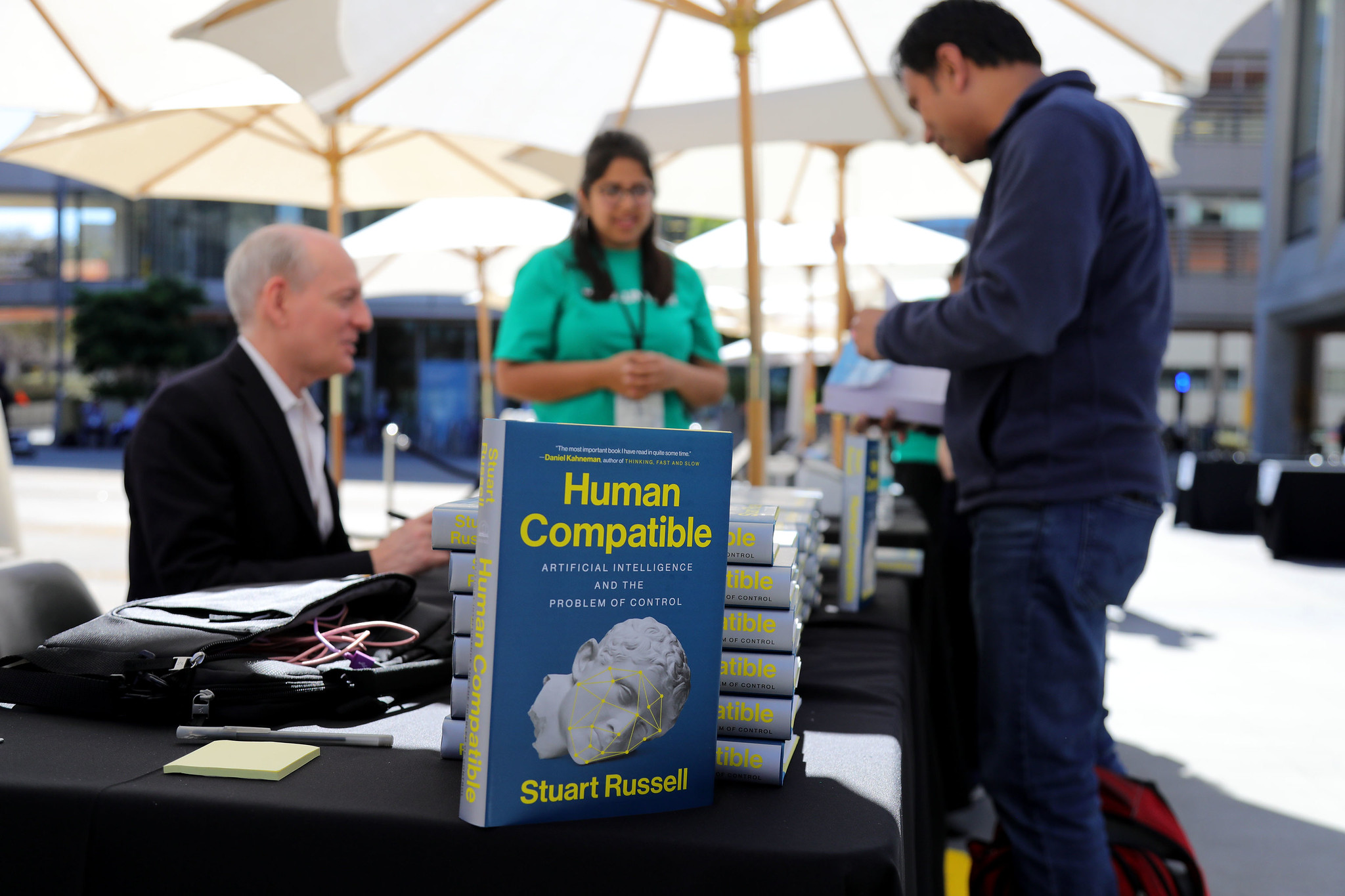

In a career spanning several decades, artificial intelligence researcher and professor Stuart Russell has contributed extensive knowledge on the subject, including foundational textbooks. He joined us onstage at TC Sessions: Robotics + AI to discuss the threat he perceives from AI, and his book, which proposes a novel solution.

Russell’s thesis, which he develops in “Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control,” is that the field of AI has been developed on the false premise that we can successfully define the goals toward which these systems work, and the result is that the more powerful they are, the worse they are capable of. No one really thinks a paperclip-making AI will consume the Earth to maximize production, but a crime-prevention algorithm could very easily take badly constructed data and objectives and turn them into recommendations that cause real harm.

The solution, Russell suggests, is to create systems that aren’t so sure of themselves — essentially, knowing what they don’t or can’t know and looking to humans to find out.

The interview has been lightly edited. My remarks, though largely irrelevant, are retained for context.

TechCrunch: Well, thanks for joining us here today. You’ve written a book. Congratulations on it. In fact, you’ve actually, you’ve been an AI researcher and author, teacher for a long time. You’ve seen this, the field of AI sort of graduated from a niche field that academics were working in to a global priority in private industry. But I was a little surprised by the thesis of your book; do you really think that the current approach to AI is sort of fundamentally mistaken?

Stuart Russell: So let me take you back a bit, to even before I started doing AI. So, Alan Turing, who, as you all know, is the father of computer science — that’s why we’re here — he wrote a very famous paper in 1950 called “Computing Machinery and Mind,” that’s where the Turing test comes from. He laid out a lot of different subfields of AI, he proposed that we would need to use machine learning to create sufficiently intelligent programs.

What people may not know is that the following year, 1951, he gave several public lectures, in which he said, oh, and by the way, and this is the quote, “we should have to expect the machines to take control.” So that was right there at the beginning — it’s not a new thing. And if you think about it, imagine you’re a gorilla or a chimpanzee, right? How do you feel about these humans? They came along, they’re smarter, they have bigger brains and my species is toast, right? So if you just think of it that way, from a common sense point of view, you have to wonder, well, why are we doing this at all? Have we thought about what happens when we succeed in creating the AI that we all sort of dream of? And Turing was completely unequivocal: We lose.

“Why is it that better AI produces worse outcomes? The answer seems to be that we’ve actually thought about AI the wrong way from the beginning.”

Why is it that better AI produces worse outcomes? The answer seems to be that we’ve actually thought about AI the wrong way from the beginning. In the book, I call this the standard model, which is a phrase borrowed from physics, they have the standard model of the forces and the unification and so on.

So the standard model of AI, we basically borrowed it from the idea of intelligence that was prevalent in the ’40s and ’50s, from economics and philosophy, namely the rational agent, the entity that has an objective and then acts so as to achieve the objective. And so the natural thing to do was to say, okay, well, machines are intelligent if they act to achieve their objectives. But of course they don’t have objectives, so we have to plug them in. So that became the standard model: You build optimizing machinery, and you plug in an objective, and off it goes.

The objective being something like, make me a coffee, or…

It could be, “fetch me a cup of coffee” or you know, “change the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere back to the pre-industrial levels.” Or, you know, “get people to spend more time glued to their cell phones.”

The problem is that, and this is not something that should come as a big surprise to anyone, the problem is we don’t know how to specify the objectives completely and correctly. And we’ve known this for thousands of years. Right? I mean, if you go back and look at any story where the god or the genie gives you some wishes, you invariably get it wrong and your third wish is please undo the first two wishes, let’s go back because I completely ruin the world. King Midas got exactly what he asked for. And then his food and his drink and his family will turn to gold and he dies.

“You get these sort of pathological behaviors, and they’re simply a consequence of more and more capable AI pursuing an incorrectly defined objective.”

A machine that has an objective like fetch the coffee, if it’s sufficiently intelligent, would realize: Oh, if someone switches me off, I will fail to fetch the coffee. Therefore, I have to defend myself. In fact, I have to take preemptive steps against any other entity that might switch me off, because I want to reduce that probability of failure as low as possible. So you get these sort of pathological behaviors, and they’re simply a consequence of more and more capable AI pursuing an incorrectly defined objective.

Because we don’t have the priorities correct — we don’t have the correct way to specify the objective.

Yeah, and it’s not just AI. This is control theory, where you minimize a loss function in economics, right? You maximize a welfare function or you maximize discounted quarterly profits. And so this is actually, when you think about it, a big part of the intellectual output of the 20th century. And it only works when your machines are really stupid. If they’re not smart enough to think about how to change the rest of the world. But we’re already seeing, you know, if you think about corporations as machines that maximize quarterly profits, they’re getting smarter — and they’re actually destroying the world. Whether you like it or not, the rest of the human race has lost that particular chess match.

Plot twist: The AI was here all along, and it was Exxon.

Exactly.

You’ve said that this has been a problem people have recognized for some time, although many researchers have taken advantage of the standard model to accomplish various practical tasks. So not everybody agrees with you on this. They think that perhaps this is not as much of a threat as you suggest it is. Do you have a response for that? Are they just in denial? Or do they have a point?

I think denial is probably the right word. Because what you see is these very intelligent, respectable people making arguments that, with all due respect, a five-year-old could see through.

One argument being well, electronic calculators are superhuman at arithmetic, they didn’t took over the world, therefore, there’s nothing to worry about.

“What you see is these very intelligent, respectable people making arguments that, with all due respect, a five-year-old could see through.”

But if the entire physics community and the, you know, big chunks of government budgets around the world and all of the top 10 largest corporations in the world, were investing all of their resources in making black holes materialize in near Earth orbit, wouldn’t you ask them if that was a good idea?

And I could go on and on. I used to, you know, I used to give talks where I would go through all of the counter arguments and then the refutations.

And you do in the book.

I think there’s also an unwillingness to exercise imagination about what would it really be like to have smart machines. If you want to see what it’s like when machines get out of the lab… so we actually had two things going in our favor. Number one, the machines are really stupid. Number two, they were confined to the lab, and often even to a simulation in the lab.

“We may have to see a much bigger, more obvious catastrophe before the world really pays attention, just as it took Chernobyl for people to take seriously the idea that, yes, nuclear power stations really can explode.”

Mark Zuckerberg.

— the corporation. Right, yeah.

So I think we may have to see a much bigger, more obvious catastrophe before the world really pays attention, just as it took Chernobyl for people to take seriously the idea that, yes, nuclear power stations really can explode.

Whether or not we have a disaster, you actually have a novel solution, or at least a proposal for a new approach, which, in retrospect, and which I think is true of the best solutions, seems sort of obvious. Essentially, to have the AI be constantly beholden to a human intelligence, to find out what it is that we want, what is good for humans.

Yeah, so if it’s not possible to specify the objective completely and correctly, then the machine had better not assume that it has the complete and correct objectives, right? Obviously.

So in other words, it knows that it doesn’t know what the objective is. So the main thing is to just think, okay, where’s the objective? And in the standard model of AI, it gets plugged into the machine’s head and now it’s in the machine.

Someone literally writes, “this is the objective,” and it is defined thusly.

Or if you get in a self-driving car, you know, you’ll type or speak the objective, or you type in the address you want to go. That becomes the objective of the algorithm, and so on. It’s a very natural thing.

“If it’s not possible to specify the objective completely and correctly, then the machine had better not assume that it has the complete and correct objectives, right?”

A lot of the time you never even thought about it. I bet most of you have never thought, you know, would you be happier if the sky was always green instead of blue? You never thought about that. But if a machine made the sky olive green as part of its climate control efforts, you’d probably be a bit upset, right? So there’s tons of stuff that is implicit in our preferences. And there’s a bunch of stuff we just literally don’t know, because we, you know, we never tasted a particular kind of food and we just don’t know our own preferences about the future, epistemically.

So the objectives are in us, and the machine knows that it doesn’t know what they are, but we design the algorithms so that the machine is obligated to try to optimize the human preferences. There’s a field called game theory, because now there are two entities here. There’s not just a machine pursuing its objectives. There’s a machine trying to optimize objectives that are in the humans.

It has to guess at those objectives, it doesn’t know them explicitly.

Game theory handles those problems. What we’re arguing basically is if you formulate the problem this way, then when the machine solves it, the better it solves it, the better the results are for human beings, as opposed to the standard model where the better the machines solve the problem, the worse the results are for human beings.

“All of the algorithms that we’ve developed, the techniques, the theorems, with new algorithms, techniques and theorems that handle the fact that the machine doesn’t know what the objective is.”

Do we really have to start from scratch? Or do you expect that the standard model will still be useful in ordinary situations, limited situations where you don’t need to worry about a super-intelligence emerging, you just want it to make the coffee. We have a little coffee making robot in the back right now, it doesn’t seem like it’s going to take over the world. But you know, I haven’t written a book about it.

I think there are there are plenty of situations where you don’t need general-purpose intelligence and you can be fairly sure that it’s safe because you give it a limited scope of access.

For example, if you design a program for playing chess. When humans play chess, you might think that they win by playing good moves. Oh, no, no, no. They win by trying to distract the opponent by fidgeting or coughing, some have actually tried to hypnotize their opponent. They bribe the referee. They kidnap people’s relatives —

Well, that I’ve tried.

They do all these kinds of things. Because they’re not stupid, right? They realize that there’s more to the world than just moving pawns and knights on the board.

But you can make a program that literally cannot do anything but move pawns and knights on the board. That’s fairly safe. Now imagine a Go program. And all it’s allowed to do is put stones on the board. But if it’s really, really intelligent, it might think to itself, just as we do, how am I here? What is this universe that I’m operating in? How does my brain work? How does the physics of the universe work to support my brain?

Those are perfectly reasonable questions for an intelligent entity to go after we’re human. And we asked it, right. Its universe appears to be accessible only through playing moves on the Go board, but it would figure out, okay, I’m computing. So there must be some physical substrate that’s producing my computational behavior.

I compute, therefore I am.

Exactly. There’s something else playing the black stones if I’m playing the white stones. Let me try to figure this out. And eventually it would start playing moves in patterns, to try to communicate with other entities that must be out there.

Spelling out, “help, I’m stuck inside a Go game.”

Yeah, so it’s very hard to prove that it can’t escape. There’s no risk from completely dumb programs. The problem is, if you wanted to have, for example, a domestic robot that has enough common sense to run your household successfully, with all the weird stuff that happens in households, it has to be pretty intelligent, right? It’s not going to be useful if it’s stupid enough to cook the cat for dinner. The company would just go out of business immediately.

We only have a little bit of time left, but I wanted to say one thing I really enjoyed about your book is you really reached into the past to get some of these older authorities. You mentioned of course Turing, who mentioned this problem early on; Norbert Wiener; even further to people like Samuel Butler’s “Erewhon;” even going back to Epicurus. I thought it was very, I thought it was fascinating that you were reaching so far back to inform a present idea about AI. Do you think that people creating AI today don’t have a broad enough knowledge base to make these kinds of large decisions?

How can I put this politely…?

I guess I didn’t ask it politely.

No. They don’t.

It’s a trend that many commentators have observed that present-day research papers typically cite nothing before 2014. You will see leading luminaries in the deep learning community talk about the possibility that they might need systems to do things like reasoning, you know, as if no one has ever thought of that before. Right, you know, as if Aristotle didn’t exist, and Quine didn’t exist and all the rest.

“There’s a massive amount of stuff that we already know how to do that I would say a lot of the modern AI community has completely forgotten, and they’re going to have to reinvent very painfully and slowly.”

Well, we have to wrap up…

Let me just mention one thing. So earlier, Devin asked me, is there one thing you would recommend that the audience read? Besides the book…

It’s free, you can download it right now, it’s called “The Machine Stops.”

[It’s available for download in several formats here.]

By E.M. Forster, and I’ve read it. It’s really, really, really interesting. Written in 1909, right?

Written in 1909. And it’s not about this particular problem, it’s about the next problem. Assuming that we don’t destroy ourselves by creating out-of-control machines, and so on, it’s the problem of overuse of AI — the fact that once AI is capable of running our civilization, we no longer need to teach the next generation everything we know about our civilization. The incentive to go through what has been up to now roughly a trillion person-years of teaching and learning, just to keep our civilization going.

When that incentive disappears, it’s very hard to keep civilization in human hands. It’s an amazing story — amazingly prescient. It has the internet. It has MOOCs. It has iPads, video conferencing, computer-induced obesity, you name it, he thought of it.

Thank you for the recommendation. And thank you for joining us.