Hi, I’m Ann.

I was one of the first investors in Lyft, Refinery29 and Xamarin. I’ve been on the Midas List for the past three years and was recently named on The New York Times’ list of The Top 20 Venture Capitalists. In 2008, I co-founded Floodgate, one of the first seed-stage VC funds in Silicon Valley. Unlike most funds, we invest exclusively in seed, making us experts in finding product-market fit and building a minimum viable company. Seed is fundamentally different from later stages, so we’ve made it more than a specialty: It’s all we do. Each of our partners sees thousands of companies every year before electing to invest in only the top three or four.

For the past 11 years, I’ve invested at the inception phase of startups. We’ve seen startups go wildly right (Lyft, Refinery29, Twitch, Xamarin) and wildly wrong. When I reflect on the failures, the root cause inevitably stems from misconceptions around the nature of product-market fit.

The magic of product-market fit

Most successful entrepreneurs and VCs agree that product-market fit is the defining quality of an early-stage startup. Getting to product-market fit allows you to succeed even if you aren’t optimized on other fronts.

Most entrepreneurs conceptualize product-market fit as the point where some subset of customers love their product’s features. At Floodgate, we forensically analyzed companies that died and concluded this conceptualization is wrong. Many failing companies had features that customers loved. Some of these companies even had multiple beloved features! We discovered that having customers love the product is merely a part of product-market fit, not the entire thing. This raises the question: What were they lacking?

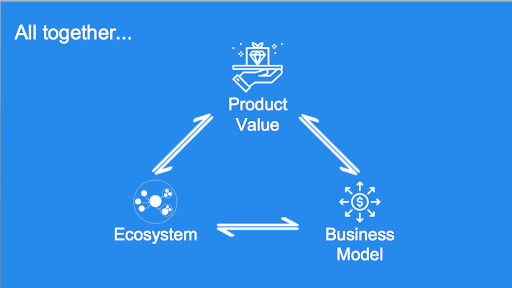

Before attempting to scale your minimum viable product, focus on cultivating your minimum viable company. Nail down your value proposition, find your place in the broader ecosystem and craft a business model that adds up. In other words, true product-market fit is actually the magical moment when three elements click together:

Great product features constitute only one-half of one-third of the whole puzzle. A company needs all three of these elements working in concert to have created a minimum viable company.

Value propositions

I often hear founders describe their product as sets of features or technological breakthroughs. Features, however, aren’t the product — they’re merely enablers of value propositions: promises of how the product will drastically improve a customer’s life.

These value propositions must be extraordinarily compelling. To succeed, a startup must be at least a 10x improvement for their customer on some dimension. Without a 10x advantage, there may be a slow increase in customer satisfaction, but the product will lack the necessary spike of delight. With no spike of delight, the company doesn’t stand a chance in enticing customers.

Indeed, 10x advantages in early days can seem borderline crazy, because products built by startups appeal to a relatively small but rabid group of customers. In the early days, Airbnb targeted locations around events that spiked demand for hotels. Their 10x advantage was a place to stay for a fraction of the cost. In Square’s early days, it enabled a wide variety of users — from artists charging thousands of dollars to farmers selling individual apples — the ability to take credit card payments from their phone. Tesla’s 10x advantage was being the first electric car with a slick design and crazy acceleration (literally called “Insanity Mode”). They also offered an autopilot option, prompting huge customer delight.

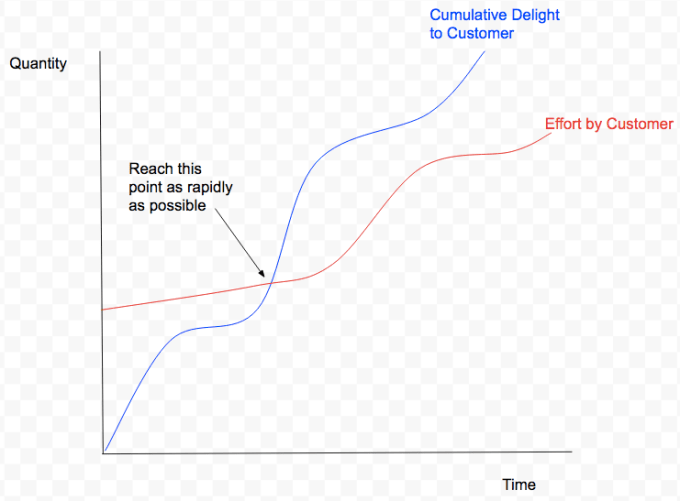

But are these enough? Optimistic, future-focused entrepreneurs often concentrate on these moments of delight. However, to reach product-market fit, a startup must also consider the implicit costs to a customer that come along with a new product, including money (e.g. the product’s price), time (onboarding/changing habits) and effort (learning to use your product).

A founder recently pitched me a company that would require would-be users to install hardware in their car and download an app before seeing any benefit. This is a large amount of customer investment. For the company to succeed, the value proposition would have to be both compelling and immediately obvious upon installation.

Before achieving product-market fit, a product’s promises of value — and its follow-through — must outweigh the costs, as quickly as possible.

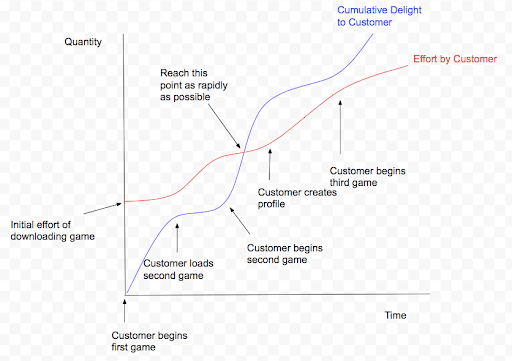

For example, most mobile games allow users to play right away (before signing up or paying), providing significant delight before requesting user investment.

Lyft’s cumulative delight overcame a customer’s investment within the customer’s first ride:

- A rider’s first moment of delight came when they expected a long lag time after ordering the car… and then learned it will pick them up in only three minutes!

- The second delight was fist-bumping the driver — it felt like a friend coming to pick you up.

- The third delight was the interior of the car — it’s not a grungy, smelly cab, but a normal car your friend might own.

- The fourth delight was the ambiance (music, water) and chatting with the friendly driver.

- The fifth delight was the price — much less expensive than a cab ride.

A week into the Lyft launch, one of our associates ran into my office with his eyes wide, shouting, “you have NO idea what you have on your hands. I’ve taken six Lyfts this week alone and it’s a GAME CHANGER!” Delight is seeing your customer’s pupils dilate because they’re so ecstatic about your 10x change.

Seeing a product as merely a bundle of features disregards the inherent blockers your product must bypass to succeed. Your product is an entire customer experience, and successful companies view it as such.

If you’re unsure whether you have a strong value proposition, look at your word of mouth. Word of mouth is organic growth (meaning it’s growth you can’t buy). When you have strong organic growth, you can be confident you have a strong value proposition. I find this single metric to be the most predictive of whether or not the product will drastically improve customers’ lives. I also pay attention to a product’s Net Promoter Score as well as Sean Ellis’ Product-Market Fit metric, which measures the percentage of users who would be “very disappointed” if they could no longer use your product (ideally this metric should be greater than 40%).

Ecosystem

Startups deliver a product to more than just their customer; they deliver it into an ecosystem. Promoters, detractors, brokers, salespeople, marketing channels and integrators all influence your customers. Each ecosystem distributes money and information in unique ways. To create a successful company, a founder must clearly comprehend the value they add, who they threaten and the methods by which their product becomes known.

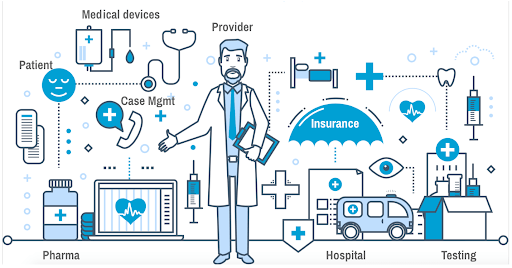

To reach product-market fit, you must anticipate how your product will be received by the ecosystem as a whole. Healthcare is a great example, as its ecosystem includes:

- Payers

- Providers

- Insurance brokers

- Health tech companies

- Patients

A startup that fails to recognize the power of insurance companies could satisfy patients but never get off the ground. We also see many startups aiming to implement AI in healthcare with no idea how they will access the patient data they need to train their algorithms. While the healthcare ecosystem is particularly fragmented, most ecosystems operate with more than two parties, be they middlemen, regulatory oversight or otherwise.

Even if a product is valuable to one group, failing to consider the behavior of another could kill the product. Lyft, for example, requires more than a healthy relationship between drivers and passengers. It requires an understanding of insurance, the economics of car ownership and the government regulations around ridesharing. Ignoring any of these critical pieces of the ecosystem would jeopardize the very existence of the company.

The ecosystem also requires a recognition of both the information flow (how knowledge about your product spreads) and the dollar flow (how you extract profits). These two flows dictate how prospective clients become paying customers.

For example, the gaming ecosystem contains a complex industry and power dynamics that are constantly shifting. Dollar flow within the gaming environment seems simple (gamers pay for games and viewers engage with brands that sponsor professional gamers), but many more people and companies also contribute to the flow. Before a game is even released, companies spend massive amounts on asset creation, level design, back-end development, quality assurance and competitive balancing to reach the increasingly high bar for a video game MVP.

When gamers pay for their games, the money goes to more than the publisher or developer. Part of the game’s retail price goes to the marketplace where it was bought (e.g. Steam). The rest of that revenue goes to the publisher, which may contribute funds to a league for the game (e.g. Overwatch League from Activision Blizzard). Outside of the game itself, there are also professional gamers who play in leagues and stream for their own followings on platforms like Twitch and YouTube. Finally, social apps like Discord enable gamers to communicate with one another.

Within a complex industry like this, it’s important to fully understand where your business is going to capture value and how all stakeholders will react to that change in the flow. For example, we’ve seen startups that help gamers improve by plugging into a game’s API. Even if the gamers love this product, the publisher may decide it creates unfair dynamics in their game play or worry it intercedes in their relationship with the gamer. As a result, it’s quite possible that the publisher will revoke your API access.

Each industry has its own nuances. Ignore them at your own peril.

Business model

Business model is much more than the price a customer pays for your product. It includes your product packaging, the cost of goods sold and how you get your product to customers.

We’ve seen many founders try to delay the question of pricing until a later time. They say they want to get in front of customers first and figure out pricing later. But pricing itself is an important question. What’s included in various pricing packages, what the packages are called and how much is being charged can influence both whether a customer buys and how much they choose to spend.

In one company we had two identical product packages. One was called “professional” at $1,000/month and the other was dubbed “enterprise” at $3,000+/month. The only difference was how quickly the customer could access customer service when they had a problem. Interestingly, customer service was run so well that there was no measurable difference between the response time for each package. Large organizations with uptime requirements were fine paying the extra $2-3,000 a month to receive the guarantee that someone would call them back quickly for any open problems or questions. This company would not have originally considered customer service a core product, but it ultimately drove both revenue and margins.

The relationship between price and cost is also critical. This is the basis for margin, which often determines how a company is valued. When it comes to company valuation, a dollar of revenue for an e-commerce business can be 5-10x less valuable than a dollar of revenue for a SaaS business. This difference is because a SaaS business typically sustains 75-80% gross margins while an e-commerce business’ gross margins typically range between 20-50%. E-commerce businesses are much more operationally complex, with higher customer churn than the typical SaaS business.

Price and cost also form the basis for unit economics. It can be easy to misperceive an end customer’s enthusiasm in receiving a bargain as a sign of product-market fit. After all, who wouldn’t love to purchase a dollar for $0.80? Too often, companies commit to scaling an unsound business model purely on the hope that, at scale, their unit economics will fix themselves. Take, for example, a food delivery service. Suppose that a customer’s order sums to $30, including fees and tip: $20 goes to the restaurant; $7 goes to the delivery person; transaction fees for this order are around $1.50, giving the food delivery service only $1.50 in profit. The only parts of the business that can potentially be optimized are the pricing pressure that a delivery company can place on restaurants (but restaurants themselves are low margin) and the density of deliveries a person can do in one run (but this is restricted to specific markets with high residential and restaurant density). It’s no wonder some of these businesses need to claim a part of the tips as a part of their revenue… otherwise, the model doesn’t work!

Your business model is the backbone of your company. We like seeing how business models interact with your company’s other components as early as possible to set the context for the business’ valuation and future growth potential.

True product-market fit is a minimum viable company

True product-market fit requires more than a valuable minimum viable product. It requires a minimum viable company. All three elements — value propositions, business model and ecosystem — must work in concert:

- People must value your product enough to be willing to pay for it. This value also determines how you package your product to the world (freemium versus free-to- pay versus enterprise sales).

- Your business model and pricing must fit your ecosystem. They must also generate enough sales volume and revenue to sustain your business.

- Your product’s value must satisfy the needs of the ecosystem and the ecosystem needs to accept your product.

So founders take heed…

Moving into “growth mode” while missing any of these elements is building your company on an unsound foundation.

Founders who tune out the latest tweet cycle on “the secrets to raising Series A” and focus instead on the intricacies of their own business will find that product-market fit is a predictable, achievable phenomenon. On the other hand, founders who prematurely focus on growth without knowing the basic ingredients of their minimum viable company often fuel an addictive and destructive cycle around their business’ fake growth, acquiring non-optimal users that contribute to their company’s destruction.