It takes guts to be a VC, but being a child actress prepared me well for the challenge.

In addition to the serial rejection even the most successful actors experience in audition after audition, life on set isn’t always a picnic. When I was on “The Wonder Years,” we filmed an episode called “The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre,” in which my character, Becky Slater, attempts to run over longtime foe Kevin Arnold with her bicycle.

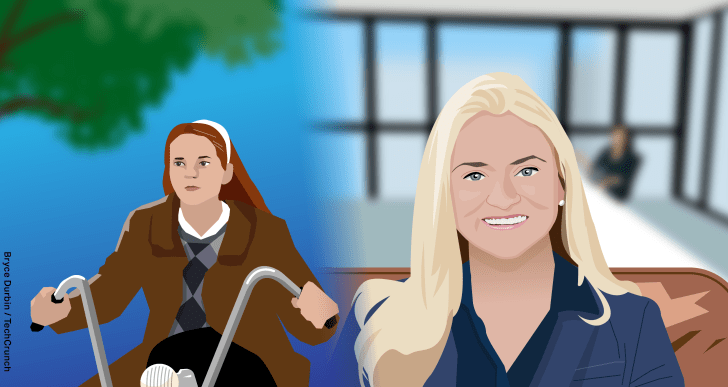

During a dress rehearsal, as I sped up on the ancient, too-tall 1960’s-era bike, my front wheel hit a thick sound cable that hadn’t been there during a prior run-through; I went over the handlebars and spent the evening in the emergency room. A few days later, barely off crutches, I was back on set and back on the bike. We filmed the scene, and the episode was one of the series’ most successful and memorable. No one has ever accused me of timidity.

Many years later, armed with degrees from Yale and Harvard Law — plus years of experience advising companies as a lawyer and investing in them as a VC — I launched my own venture capital fund, Anathem Ventures. The grit and perseverance I first honed on studio soundstages serves me well, and these are also the qualities I look for in the founders I back.

Anathem Ventures CEO/founder Crystal McKellar

It takes guts to be a great investor. It takes guts to build and back companies operating on the technology frontier — startups solving problems that have never been solved before using new technology. I’m not talking about yet another food delivery app or on-demand dog walking service, but truly breakthrough tech.

A lot of venture capitalists take comfort in pattern matching: does this company look like something I’ve seen before that was successful? If it looks comfortably familiar, they invest. If the company appears disconcertingly new, they take a pass. But if all you’re doing is pattern matching, you’re behind the curve and investing in the “also ran” that will in turn be pursued by even more copycats. Investing in truly novel tech is what brings to our investors the venture returns we are in this business to provide. The anodyne of pattern matching, while superficially comforting, leads down a much less lucrative path.

One of my founders tells a story in which she was practically thrown out of a room at a large medical conference. Her crime was to suggest a novel tech solution to the costly problem being discussed at the conference. The people in the room reacted angrily, telling her that what she suggested was too technically difficult, that if it were feasible it would already have been done, and that she likely would fail if she tried. Humans are often resistant to change and progress, and these otherwise educated people were uncomfortable and angry at the thought of an innovation that looked nothing like what existed already. Luckily, she ignored the timid naysayers, developed the tech and is off to the races with legions of happy customers. She has guts in spades.

It takes guts to invest when others don’t “get it,” and a great investor needs to be comfortable operating independent of the pack. If I develop conviction around a team, the superiority of their proprietary tech, their ability to execute and their ability to win and own a high-margin market, I’m not looking for validation in the identities of the other investors who are investing alongside me. The venture capitalist who looks for a positive signal in the identities of the other firms joining the investment round (and conversely who sees a negative signal if the other investors are not brand name funds) is just abdicating their own investment judgment to others.

And this happens all the time, because investing with the consensus of the “smart money” can feel comforting. It also rarely generates outsized returns, because when a lot of large funds get excited about the same company, they tend to bid the valuation up, eliminating much of the potential upside.

Outsized returns are generated when an investor identifies a valuable opportunity that is under-appreciated by others and is therefore able to invest at an “undervalued” (i.e. not bid-up) price. This takes conviction.

On the flip side, a great investor also has to have the courage to walk away from a deal when it “breaks” — perhaps you learn something unsavory about the CEO, that the company has been cutting corners on compliance or that it has been less than honest during diligence. I have seen well-regarded venture capitalists ignore such red flags because they trusted more in the prestige of the other investors around the table than in their own judgment.

As a young lawyer, I learned that when you see a red flag, you pick it up. I still do. It takes guts to walk away from a name-brand deal when others seem willing to overlook red flags, but great investors do it anyway — we owe it to our own investors who entrust their capital to us.

It is the necessity for this kind of individualistic courage in venture capital that leads Peter Thiel to ask his now-famous interview question, “what important truth do very few people agree with you on?” As he explains, the question measures not only the intelligence of the interviewee, but also her courage. It takes guts to give an answer you know will be unpopular.

It takes backbone to fight for the right outcome for your CEOs when the other investors around the table are trying to squeeze them or convince them to switch course on the company’s direction. And it takes guts to act with integrity when self-interest appears to steer in the other direction. But the seeming ease of a dishonest path is illusory; choosing integrity is always worth the short-term cost, and pays dividends in the long run. This is another lesson I was lucky to learn during my childhood.