Lidar sensors are likely to be essential to autonomous vehicles, but if there are none of the latter, how can you make money with the former? Among the industry executives I spoke with, the outlook is optimistic as they unhitch their wagons from the sputtering star of self-driving cars. As it turns out, a few years of manic investment does wonders for those who have the wisdom to apply it properly.

The show floor at CES 2020 was packed with lidar companies exhibiting in larger spaces, seemingly in greater numbers than before. That seemed at odds with reports that 2019 had been a sort of correction year for the industry, so I met with executives and knowledgeable types at several companies to hear their take on the sector’s transformation over the last couple of years.

As context, 2017 was perhaps peak lidar, nearing the end of several years of nearly feverish investment in a variety of companies. It was less a gold rush than a speculative land rush: autonomous vehicles were purportedly right around the corner and each would need a lidar unit… or five. The race to invest in a winner was on, leading to an explosion of companies claiming ascendancy over their rivals.

Unfortunately, as many will recall, autonomous cars seem to be no closer today than they were then, as the true difficulty of the task dawned on those undertaking it.

Velodyne has been in some ways the poster child for lidar and in others, its ugly duckling. Its “KFC bucket” spinning-laser lidar units were the first to see widespread use by experimental autonomous vehicles and became synonymous with the general effort. But spinning lidar units are expensive and mechanically complex, making them impractical for production vehicles, which led a new generation of lidar companies to completely abandon that approach.

But the company’s new CEO, Anand Gopalan — announced the same day I spoke with him — said the company is evolving with the industry and is not a one-hit wonder, as its competitors tend to paint it.

Exhibit A is the Velabit, a tiny lidar sensor with limited capabilities, but a price tag under $100.

“There’s no argument about the market opportunity for lidar,” said Gopalan. “I think the right conversation is about what you want to do with it. Others are focused on level 2+ or 3 [autonomy, i.e. above simple driver assistance] — what we want to do is short-circuit that approach. The only reason it’s not being adopted at lower levels is price. If I say you can have lidar for a hundred dollars, of course you’re going to use it. Under a hundred dollars, you can’t even imagine the applications you open up: drones, home robotics, sidewalk robots.”

Velodyne has spent the last few years investing in its own processes and basic components primarily to get costs down — but to diversify, not sell more buckets. He said the company has had conversations with most automakers and that the opportunity is extending to consumer solutions. A $100 lidar is something of an end-run around competitors that are still taking aim at next-generation luxury vehicles with ADAS systems that aspire to full autonomy.

Baraja is one such competitor, one whose approach is among the most original and elegant I’ve encountered. Co-founder and CEO Federico Collarte explained to me why the company remained in stealth during the funding madness a few years back.

“The people who needed to know already knew about us,” he said, noting that lidar startups are risky and there was always going to be major attrition.

“We’re compounding risks: we’re a startup and our customers are startups,” he said. “Not many of these startups are unique, but many are running out of money. Because they have not solved the autonomy problem, the volumes are too small.”

“If you don’t differentiate, you die,” he concluded. Without differentiation, companies can’t attract long-term investors and partners, the best way to survive without a substantial customer base.

In his view, the technology matters so far as it solves the problem your partners are trying to solve. In Baraja’s case, a clever optical approach allows it to avoid interference from other lidars while providing intelligent beam steering, physical robustness and a wide field of view, among other benefits. It’s the kind of solution that a major manufacturer could feel comfortable going with on a 10-year plan. But it would have been folly to go to market any time before that, Collarte said.

Innoviz has weathered the storm of would-be competitors as well, with a more traditional MEMS-based lidar it’s honing to automotive grade with the help of BMW.

VP of Product Mati Shani said that while autonomy is a worthwhile goal, it’s not one companies can really design for.

“It’s like any technology: there’s a big hype, then the realization that the task is more difficult than they expected,” he said.

His opinion — which seems reflected in the Innoviz business — is that automakers cite “maturity, reliability and price” as their top criteria when evaluating a new technology for adoption.

That sounds conventional, but multinational corporations don’t always have the privilege of being mavericks. Therefore, Innoviz took a known and reliable technology, refined it and subjected it to BMW’s rigorous — I’m tempted to say “brutal” from Shani’s description — testing and certification process.

Crossing the development-focused business of Innoviz with BMW’s uncompromising internal processes was transformative, he said. The integration prepared them for automotive deployment and helped the company better understand their own product. Even if it hadn’t led to practical improvements, working with BMW put them in a better position to service future customers.

Shani said he saw the necessity of looking outside the automotive industry. One possibility he indicated was in “smart cities,” the latest ill-defined tech buzzword. Lidar could be used in place of CCTV or traffic cameras, providing much the same or even improved capabilities, but without the ability to identify individuals — something privacy activists and wary municipalities might jump at.

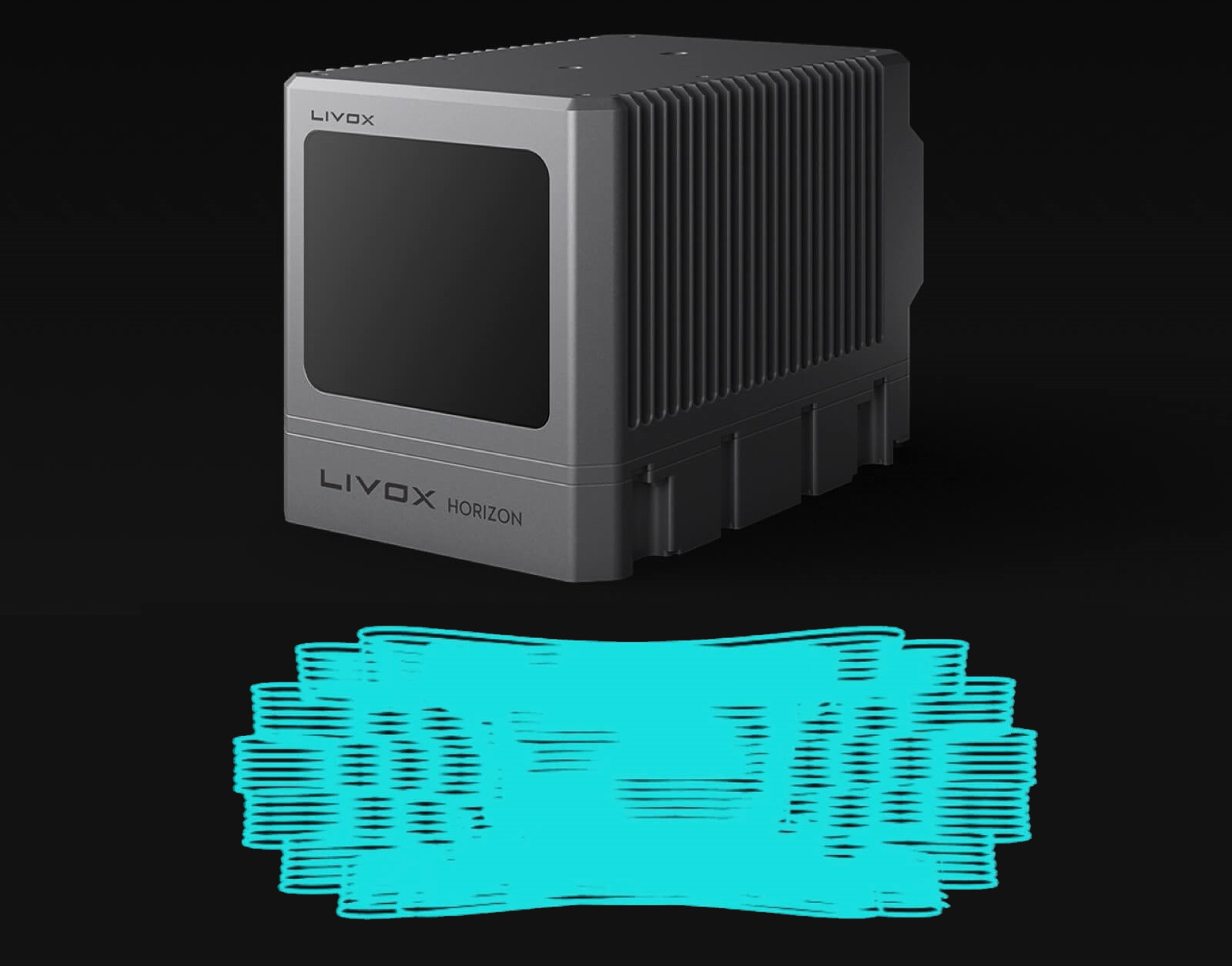

Drone manufacturer DJI is not a name generally associated with lidar, but it has entered the game anyway with the incubation of Livox, which is perhaps most like the companies that have fallen by the wayside over the last few years. Using an unproven method that involves swinging the beam across the scene in something like a figure 8, its lidar is a specialty item — but DJI knows how to ship things.

“We can’t continuously bring concepts to customers year after year,” said Henri Deng, Livox’s global marketing director. His company’s lidar units may be unusual and suited for industrial rather than automotive purposes, he said, but they’re ready for production. Deng said the focus is to get into the market to prove the product works — from there, the price will only go down and performance up. Hopefully, customers will multiply.

With a wealthy, motivated patron like DJI, Livox can live as long as necessary to accomplish that goal — and the parent company gets the benefit of in-house tech (Livox is independent, but DJI is closely involved).

The consensus I detected was that you can live without customers if you are planning — and budgeting — for an uncertain future.

That’s not easy in an industry like lidar, where R&D and scaling costs are high and the most high-profile application never seems to get any closer. Designing for autonomy is impossible and may in fact lock a company out of near-term market opportunities. Faithful investors and partners are a boon for a new company in any industry, of course, but there have been many investments in lidar and few have panned out.

But as the industry’s leaders repeatedly pointed out, there was never really a market to grow in before — and that’s changing.