It’s gotten to the point now where a handful of angel investors can put a space company on the map. But the same changes that have made the industry accessible have made it increasingly complex to track its trends. By default, all space startups are exciting, but companies vary widely in risk, capital intensity and maturity. Here’s what you need to know about the four main areas of the new space economy.

Launch: playground of billionaires and forward thinkers

Perhaps simply the most exciting industry to be a part of today, orbital launch service has gone from a government-funded niche dominated by a handful of primes to a vibrant, growing community serving insatiable demand.

There’s a good reason why it was dominated for so long by the likes of ULA, whose Delta rockets took up a huge majority of missions for decades. The barrier to entry for launch is huge.

As such there are three ways to enter the sector: brute force, stealth, and novelty.

Brute force is how SpaceX and Blue Origin have managed to accomplish what they have. With billions in investment from people who don’t actually care whether money is made in the short term (or with Bezos, even in the long term), they can perform the research and engineering necessary to make a full-scale launch platform. Few of these can ever really exist, and participation is limited when they do. Fortunately we all reap the benefits when billionaires compete for space superiority.

Stealth, perhaps better described as smart positioning, is where you’ll find Rocket Lab. This New Zealand-based company didn’t appear out of nowhere — look at its timeline and you’ll see scaled-down tests being conducted more than a decade ago. But what founder Peter Beck and his crew did was anticipate the market and work doggedly towards a specific solution.

Rocket Lab is focused on small payloads, delivered with short turnaround time. This avoids the trouble of competing against billionaires and decades-old space dynasties because, really, this market didn’t exist until very recently.

“Responsive space, or launch on demand, is going to be increasingly important,” Beck said. “All satellites are vulnerable, be it from natural, accidental, or deliberate actions. As we see the growth and aging of small sat constellations, the need for replenishment will increase, leading to demand for single spacecraft to unique orbits. The ability to deploy new satellites to precise orbits in a matter of hours, not months or years, is critical to government and commercial satellite operators alike.”

Rocket Lab’s tenth launch, nicknamed “Running Out of Fingers.”

Investing in Rocket Lab early on would have seemed unexciting as for year after year they made measured progress but took on no cargo and made no money. Patience is the primary virtue here. But investors with foresight are looking back now on the company’s many successful launches and bright future and marveling that they ever doubted it.

The third category of launch is novelty: entirely new launch techniques like SpinLaunch or Leo Aerospace. The term may not inspire confidence, and that’s deliberate. Companies taking this approach are high-risk, high-reward propositions that often need serious funding before they can even prove the basic physical possibility of their launch technique. That’s not an investment everyone is comfortable making.

On the other hand, these are companies that, should they prove viable, may upend and collect a significant portion of the new and growing launch market. Here patience is not so much required as extra diligence and outside expertise to help separate the wheat from the chaff. Something like SpinLaunch may sound outlandish at first, but the Saturn V rocket still seems outlandish now, decades after it was built. Leaving the confines of established methods is how we move forward — but investors should be careful they don’t end up just blasting their cash into orbit.

Craft: A growth industry fueled by falling costs

The point of launch is, of course, to get spacecraft into orbit or beyond. And here too things are changing — but in ways that mirror terrestrial businesses in a far more relatable sense. The changes to the world of spacecraft (a term that refers to any space-going piece of electronics, really, from the tiniest satellite to a large cargo-bearing ship) are much the same as those that led to the smartphone revolution.

Few people can claim to understand this better than Planet founder and CEO Will Marshall, who described the new changes as follows:

“We’re in a Space Renaissance, driven by radical shifts in the sector,” he said. “Firstly, satellite miniaturization: satellites are now being developed at 1000x lower mass than they were 10 years ago for the same capability. This is due to the underlying trends of miniaturization of electronics, as well as more risk tolerant postures. This is enabling new large satellite fleets to offer services like global broadband communication or daily imaging of the entire Earth.”

Changing what a hundred grams of electronics can do changes the entire business proposition around putting it in space, just as it does around putting it in someone’s pocket.

The costs involved in spacecraft have always been rather difficult to pin down, and that hasn’t changed. The rigors of designing and engineering for space are still far beyond ordinary consumer or enterprise electronics, and even though economies of scale are beginning to come into play with mega-constellations like Planet’s and Starlink’s, it’s still nothing like the rest of the manufacturing world.

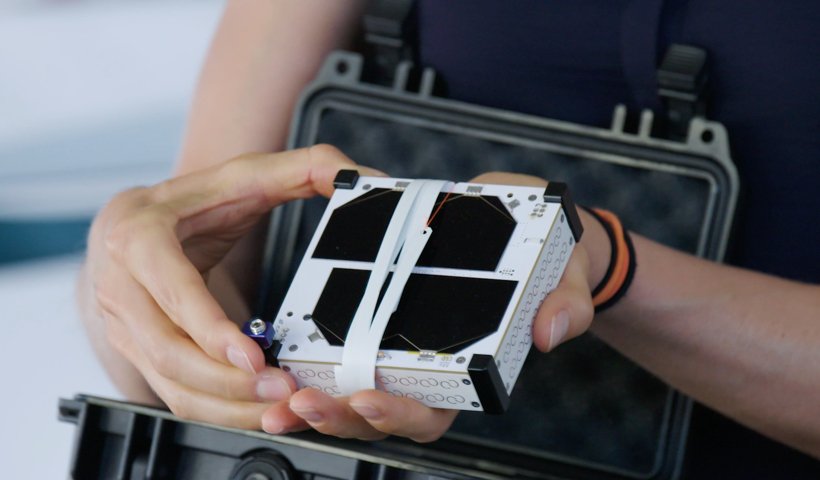

Sara Spangelo, founder and CEO of Swarm Technologies, has experience taking a new, highly compact, and inexpensive (relative to other spacecraft) satellite from concept to launch.

“For investors interested in space startups, it’s important to take a critical look at the team’s ability to launch functional satellites in space, their capacity to overcome regulatory hurdles (particularly in developing a globally coordinated spectrum strategy), and the uniqueness of their market offering. No matter how cool the technology is, the team’s ability to execute against the business opportunity should be clear,” she said.

On the other hand, launch costs have dropped considerably, a savings that trickles down to spacecraft design by lowering the overall financial risk of a mission.

“Very recently, we have begun to see changes in the launch sector including lower cost launch by close to 10x, and flexible nano rockets enabling more flexibility for small satellite development,” said Marshall.

Peter Beck also sees the eventual convergence of the spacecraft and launch markets: “As space becomes more accessible through launch, the next barrier is spacecraft hardware. The ability to go to one provider for your satellite build and launch will drive efficiency and speed, enabling satellite operators to focus on their business, science or research, rather than building their own hardware.”

The effect of all this is more craft in orbit, of course, increasing the importance of the next two sectors of the new space economy.

Ground: Make haste slowly with infrastructure

Most of the things we launch into space need to communicate with the Earth somehow, and the infrastructure to do this needs to advance at an equal pace if its proprietors don’t want to be shunned as the bottleneck holding back the industry.

Part of this is, as in the telecommunications industry, a matter of simply building things. You can’t have high speed internet without laying cable, and you can’t have a high speed space internet without laying space cable. Barring unforeseen developments in that department, we’re going to have to rely on wireless technology for the time being. That means base stations and infrastructure — but it also means merging aging space communication paradigms with agile 21st-century ones.

“Innovation in the ground segment today has to be focused on making the complex simple and automating operations wherever possible,” said CEO of Atlas Space Operations, Sean McDaniel. “This must include investments in cloud-enabled technologies, exploring artificial intelligence techniques and applications, and a focus on cyber security.”

Does that sound a bit like bringing any other legacy industry in line with modern standards and practices? It should, because it is. That makes ground perhaps the easiest place to make a smart, straightforward investment. These aren’t companies looking to change the world, they’re looking to empower those that are.

Yet at the same time, the companies providing ground support are absolutely crucial and highly specialized. As the glue that binds together space and surface, that makes intuitive sense. We’re going to need lots of glue.

Data: Open season for startups

One step further removed from orbit in a way is the data economy that’s growing around the amazing information being sent back at ever-increasing rates from satellites and other spacecraft.

“As launch becomes readily available and it’s easier to get spacecraft on orbit, the focus will increase on the analysis of data from small sats and its application in science, business and research down here on Earth,” said Beck.

Like the ground infrastructure piece, this is specific to space but not in space, and what’s more it has a very low barrier to entry, making it highly accessible to startups. There’s tons of data out there — some proprietary and protected, to be sure, but much of it available with standard APIs and access methods.

What insights are waiting in this data? How can it be combined with existing datasets to provide value? How can it be made more accessible to begin with? These questions are very similar to those being asked in data economies emerging around consumer behavior, enterprise databases, tax forms, and a hundred other areas where the flood of information has yet to be even partially tamed.

“With the addition of powerful machine learning to pull insights from these massive datasets, the Space Renaissance has created a greenfield of opportunity for investors and decision makers,” said Marshall.

But like the data economy on the ground, this one will be flighty and difficult to predict. The similarities here are more to the AI startup economy than anything actually space-related. AI and machine learning are critical to many businesses, of course, but the claims can be remarkably hard to evaluate.

As with AI, then, a general rule of thumb is to be skeptical of any claim that claims “advantage by association,” a phrase I just coined where they say what they do is better than the status quo simply because it uses a powerful technology. “AI-powered” is frequently not so, and even if a product is, that’s no guarantee it’s better than any other method. Only real results can show that.

Similarly, space-based data plays are not necessarily better than terrestrial or traditional ones. Why is data from space-based sources valuable, specifically? How does it improve outcomes, specifically? How will orbital imagery, or what have you, change your current business model, specifically? The questions relevant to success in this sector are much more akin to those in traditional software startups.

These four corners are only a bird’s-eye, or rather orbital imagery, view of a sprawling and quickly evolving industry, and each year and even month brings new advances that few could have predicted. Although areas like launch are unlikely to advance by leaps and bounds instantly, and data plays can move quicker than is perhaps advisable, they both present opportunities to the savvy investor or forward-thinking engineer or CEO.