The writing is on the wall for Facebook — the platform is losing market share, fast, among young users.

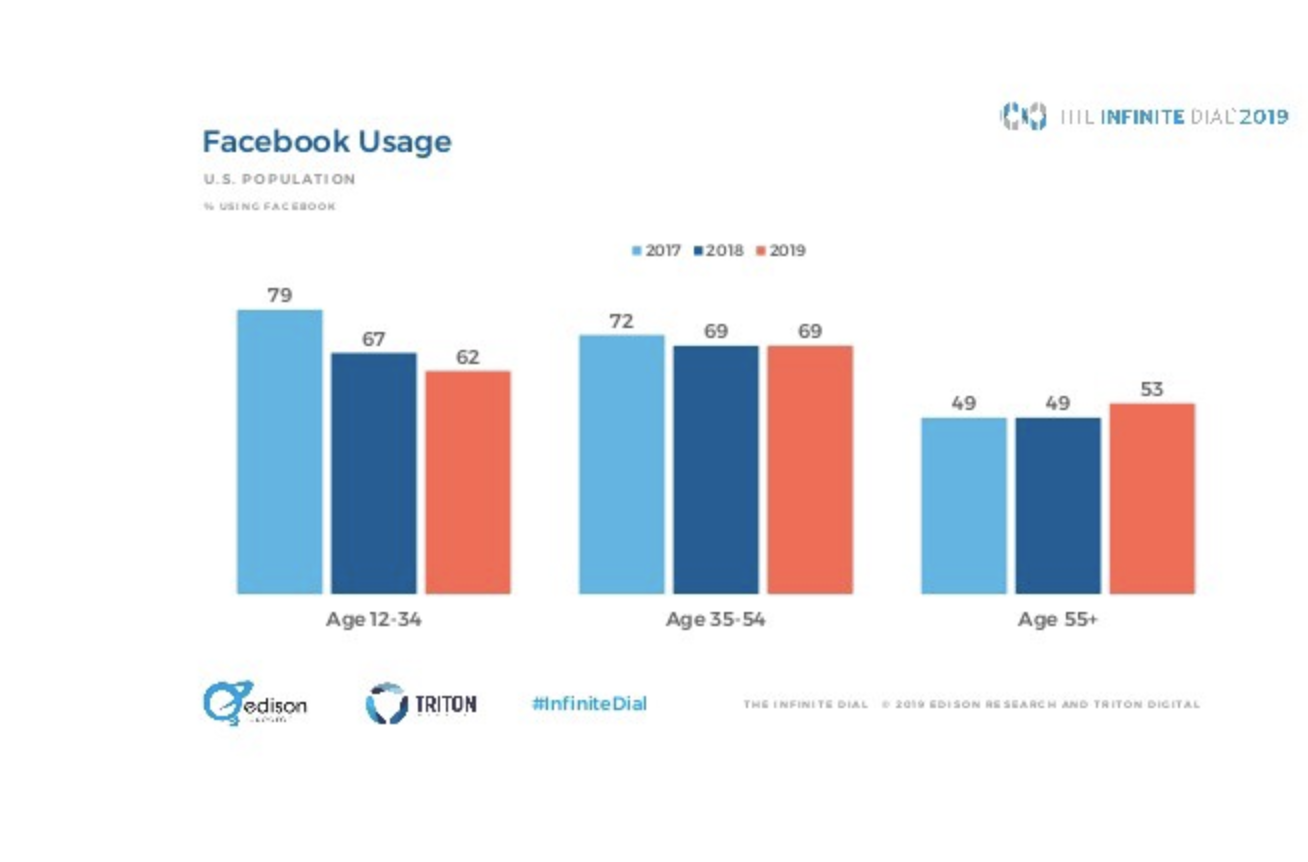

Edison Research’s Infinite Dial study from early 2019 showed that 62% of U.S. 12–34 year-olds are Facebook users, down from 67% in 2018 and 79% in 2017. This decrease is particularly notable as 35–54 and 55+ age group usage has been constant or even increased.

There are many theories behind Facebook’s fall from grace among millennials and Gen Zers — an influx of older users that change the dynamics of the platform, competition from more mobile and visual-friendly platforms like Instagram and Snapchat, and the company’s privacy scandals are just a few.

We surveyed 115 of our Accelerated campus ambassadors to learn more about how they’re using Facebook today. It’s worth noting that this group skews older Gen Z (ages 18–24); we suspect you’d get different results if you surveyed younger teens.

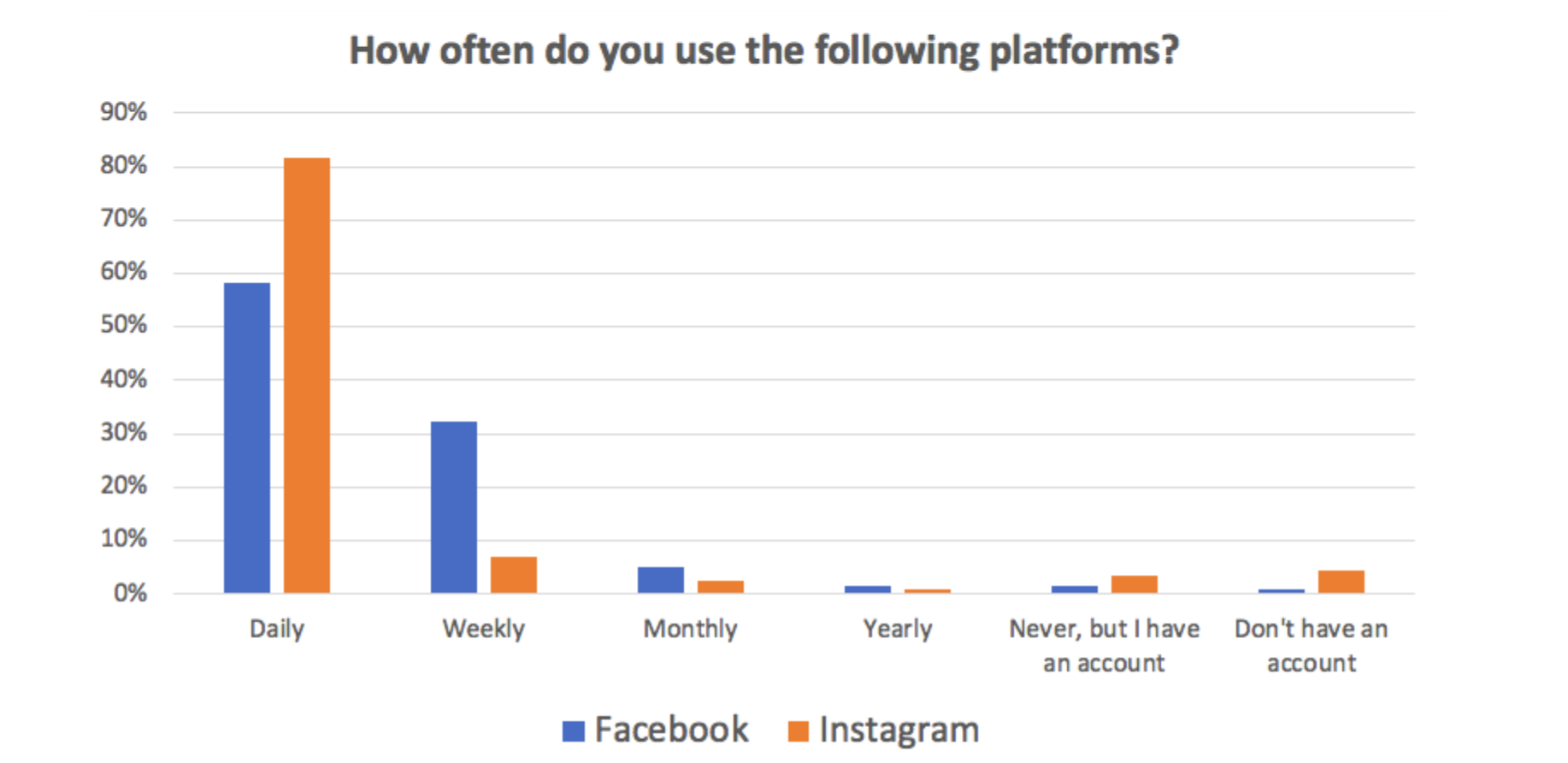

Overall penetration is still high, as 99% of our respondents have Facebook accounts. And most aren’t abandoning the platform entirely — 59% are on Facebook every day, and another 32% are on weekly. Daily Facebook usage is much lower than Instagram, however, which 82% of our respondents use daily and 7% use weekly.

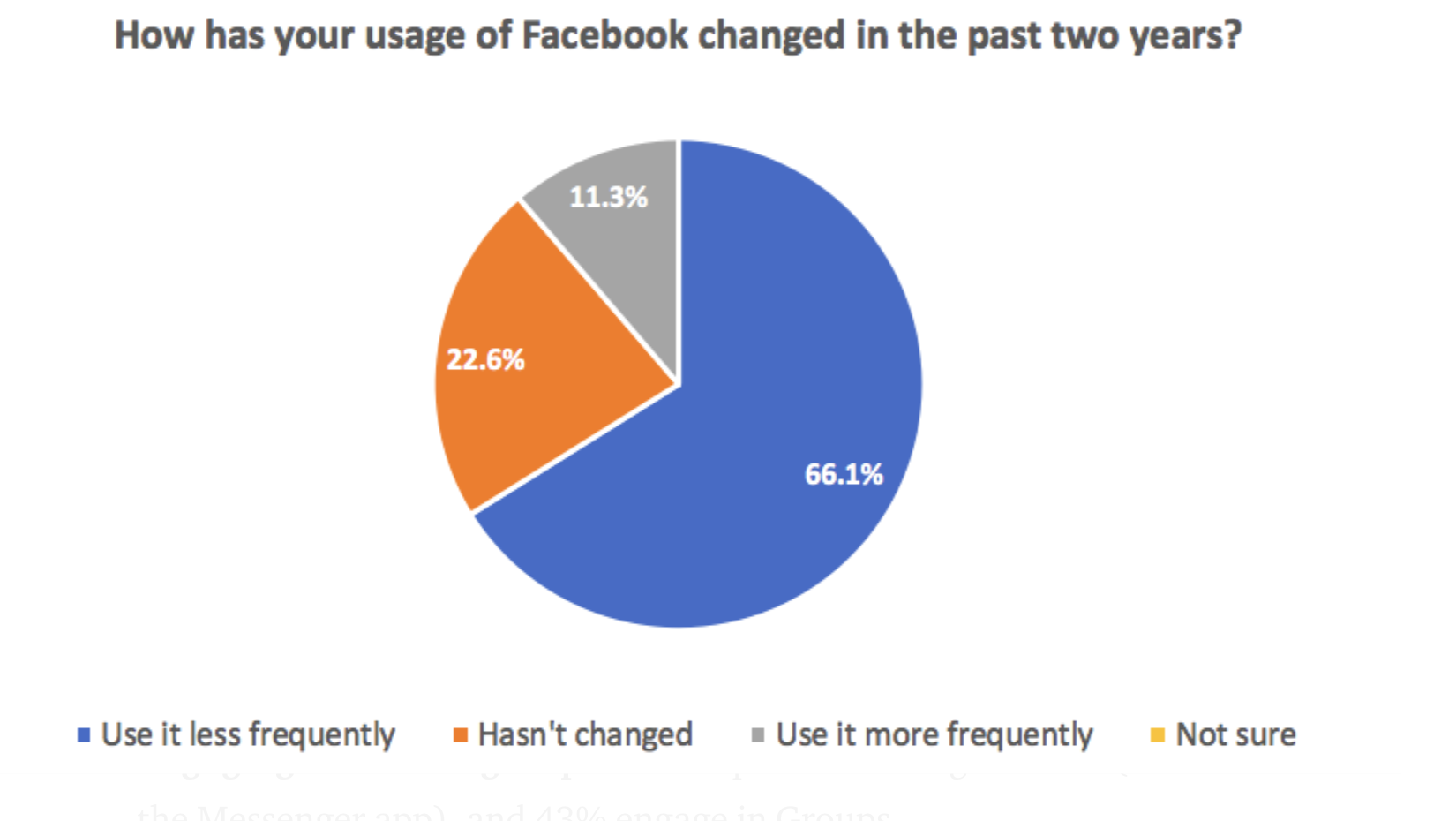

Data from our scouts also confirms that the shift in usage in the last few years is particularly dramatic among younger users. 66% report using Facebook less frequently over the past two years, compared to 11% who use it more frequently (23% say their usage hasn’t changed).

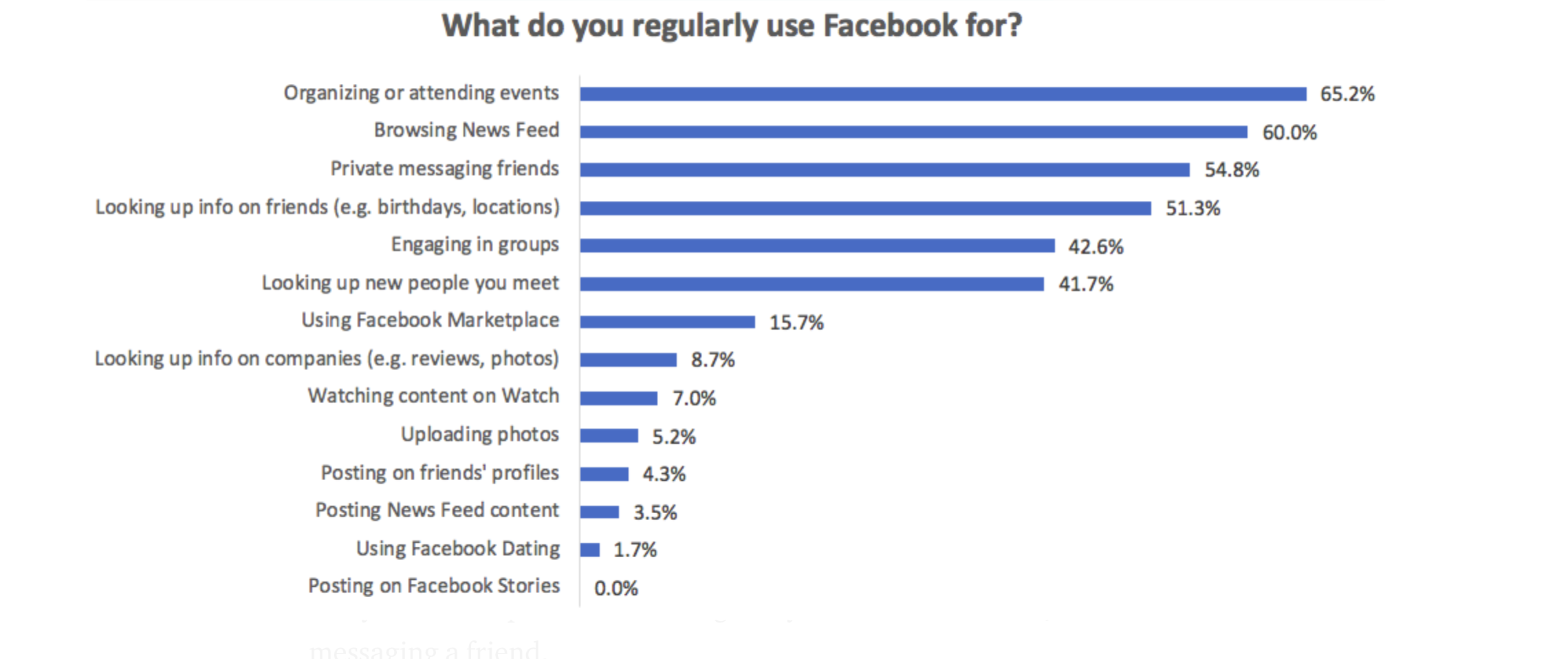

What’s most interesting is what college students are using Facebook for. When we were in high school and college in the early/mid 2010s, our friends used Facebook to post (broadcast) content via their status, photos, and posts on friends’ Walls. Today, very few students use Facebook to “broadcast” content. Only 5% of our respondents say they regularly upload photos to Facebook, 4% post on friends’ Walls, and 3.5% post content to the Newsfeed (statuses). What are they doing instead?

- Coordinating events — 65% use it to organize or attend events.

- Consuming content — 60% browse Newsfeed.

- Looking up info — 51% use it to look up information on friends (e.g. birthdays), and 42% use it to look up new people they meet.

- Engaging in smaller groups — 55% private message friends (often in the Messenger app), and 43% engage in Groups.

At first glance, it doesn’t seem like this change in use cases is necessarily problematic. Though Gen Zers are posting less on Facebook, they’re still using the platform for other things. However, we believe that these other use cases will degrade over time as users switch to consumption mode. Why?

- If users aren’t posting content, they‘re naturally going to open the app less often — they aren’t waiting to see how many responses or likes they get on their content. If they’re not on Facebook anyway, they’re less likely to use the platform for things they could do elsewhere, like messaging a friend.

- If users are coming to just to browse, they’re seeing less relevant content (because their closest friends have also stopped posting), so their feeds are probably full of ads and random content from older family members and acquaintances. They’re going to spend more of their browsing time on platforms like Instagram that serve them more relevant content.

- If users are coming to look up information (like birthdays or where a friend works), they’re only on Facebook sporadically, and it’s getting increasingly likely that the information will be inaccurate (because others aren’t updating their profiles). If they open Facebook, it will be fleeting, and they’ll lose trust in the platform as a source of information over time.

It’s a vicious cycle that will lead to gradual user churn, as users migrate these use cases to other platforms. Given this, it’s clearly a good time to be building a new app to replace Facebook. Gen Zers are using Instagram and TikTok for some of these use cases, like browsing and posting content. But photo and video-only networks face inherent challenges, and aren’t great for things like group conversations, coordinating events, or even looking up another user’s basic info.

We’ve found that many teens today are cobbling together several products to meet their needs (like sending party invites via private Instagram accounts). They may post and browse on Instagram, private message their friends on Snapchat, and just use texting for coordinating events and chatting in groups. Having to switch between these platforms is inconvenient and annoying — why isn’t there one “super app” that does it all?]

If we expect to see the rise of a new social network that truly replaces Facebook, the obvious question is whether that app will come from within the Facebook ecosystem or outside of it?

Facebook is allocating resources to ensure it’s the former, and announced this summer that they now have a New Product Experimentation (NPE) team that will create and test new apps. (Check out this recent NYT article for more on the NPE team’s strategy). We’ve started to see some early efforts from this team, including Bump, Aux, and Whale.

However, it’s worth noting that in its 14 years of existence, Facebook hasn’t demonstrated an ability to create and scale a successful standalone app (with the exception of Messenger Kids — while Messenger is part of the core platform, Messenger Kids targets a different audience with significantly different features). There’s two parts to this:

- Can Facebook incubate differentiated ideas for standalone products that could eventually become viral hits?

- Can differentiated products scale to become category leaders if they’re operating under the Facebook umbrella?

We’ll start with #2, which is easy to answer by looking at Facebook’s acquisitions of WhatsApp and Instagram. Though it’s debatable how much credit Facebook deserves for their continued growth, both companies have scaled significantly post-acquisition — Instagram from 30M to 1B+ MAUs, and WhatsApp from 450M to 1.6B+ MAUs.

#1 is more difficult to answer, because it hasn’t happened before. Facebook has tried (and failed) many times to launch standalone apps, including Slingshot, Poke, Rooms, Riff, Notify, and Paper.

To look at the positives, there’s a few reasons why Facebook has a significant advantage in launching a standalone social app:

- Talent. Facebook has the money and clout to hire top product thinkers (sometimes by acquiring their companies), and could put these people to work on new products.

- Scale. Facebook has billions of MAUs across its platform. If Facebook used the platform to promote a new product (which they haven’t done to date), this would be a significant distribution advantage.

- Resources. As a large public company, Facebook has significant resources (in terms of both $ and employees) to allocate towards spinning up and iterating on new apps, far beyond the means of any early stage startup.

- Network leverage. As Instagram has illustrated, there’s benefits to being integrated with Facebook’s social graph — they’re able to auto-populate suggestions of people you should follow, which makes it easy for users to find friends and get “locked in” to the platform.

- Press. If Facebook launches a new product, it’s going to get attention in the press, which could lead to a significant jump in new users.

And here’s a few reasons why it would be difficult for Facebook to incubate the “next big thing”:

- Cannibalization. As we’ve seen with Facebook’s efforts to launch new apps, they’re not building new platforms — they’re focused on standalone products like social music listening. There’s likely fear of cannibalizing the core app, which continues to grow (though growth has essentially flatlined in more mature markets, like the U.S. and Europe).

- Culture. While Facebook can hire top talent, it’s not known as a place for the most innovative young people to build something new. The people who have the deepest conviction in an idea for a new social app likely won’t choose to build it inside Facebook.

- Bureaucracy. Within a large company like Facebook, it can be difficult to get a new product launched. A few people at a small startup can make a decision to ship product, while Facebook has to review and get sign-offs from separate engineering, product, legal, and communications teams. This gives startups a significant advantage in getting products to market more quickly (or at all).

- Prioritization. As a public company, Facebook needs to prioritize the products that have achieved scale and drive revenue (the core Facebook app, Instagram, and WhatsApp). Experimental products will likely get less attention from the executive team, and may be the first to go if the company is pressured to cut expenses or reallocate headcount.

- Oversight. The press and politicians are looking for opportunities to attack Facebook. New products, particularly those that target teens, risk attracting negative attention and potentially new regulations. Many new social products generate buzz by being controversial (like Snapchat with sexting!), and Facebook can’t take that PR risk.

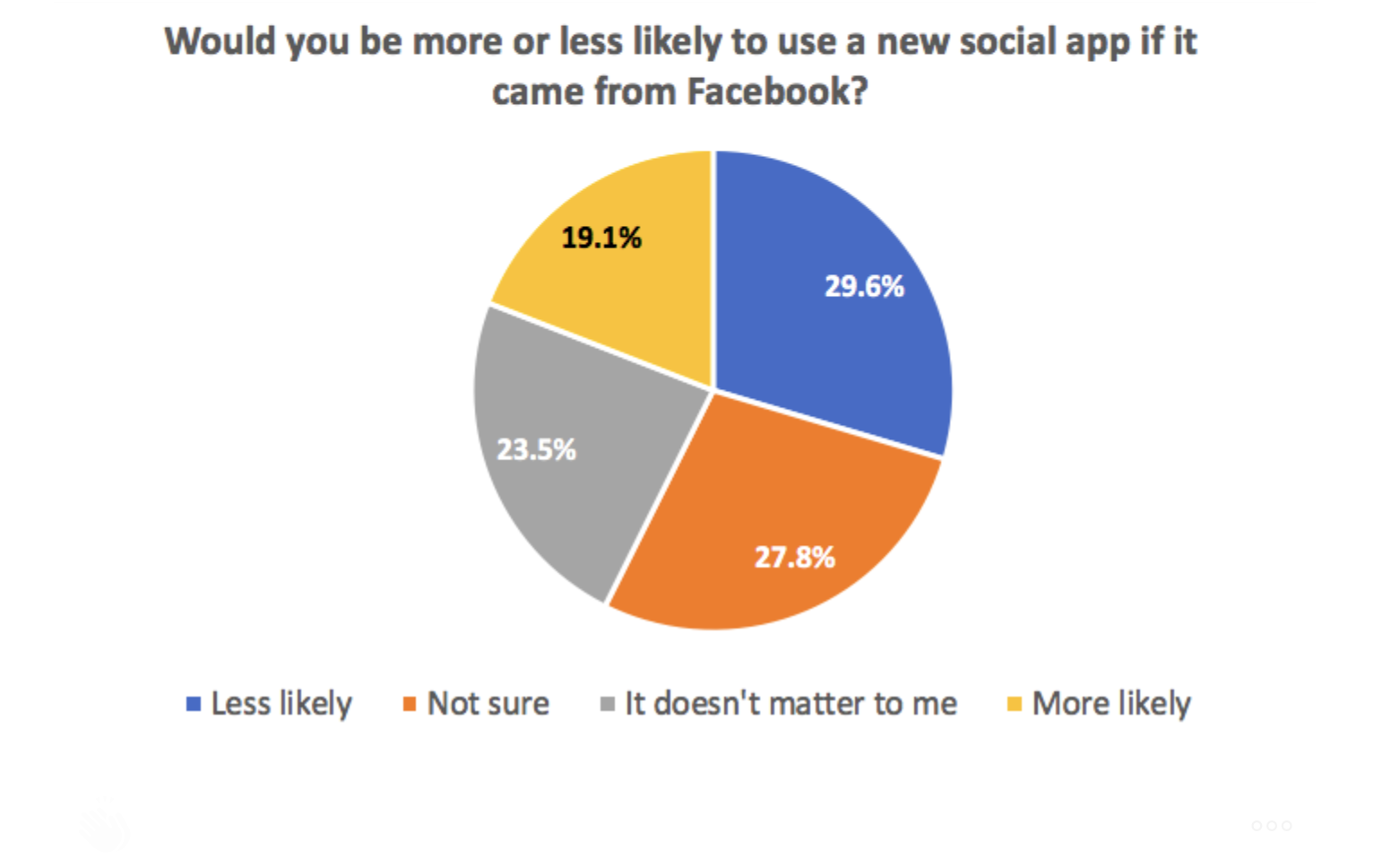

- Brand. Being associated with Facebook could make a new app seem “uncool” or overly corporate, and as mentioned above, Facebook can’t lean into a new app being too “edgy.” We asked our ambassadors if they’d be more or less likely to use a new app from Facebook— the plurality (29%) said they’d be less likely to use it, and 28% said they were unsure.

Thanks for taking the time to read this! We’d love to get your thoughts on the decline of Facebook as a “broadcast” platform, and whether the next big social app can come from within the Facebook ecosystem. Tweet us at @venturetwins.

If you’re building something new in consumer social, we’d love to hear from you — please email us at twins@crv.com.