There has been a mountain of press lately about how investors are souring on unprofitable unicorns.

We’ve seen this movie before; for a while, it’s all about growth, and profits be damned, then the winds change, and everyone focuses on “capital efficiency,” or similar jargon meaning, “how can I get big returns without having to put much money at risk?”

The winds blow back and forth. Until very recently, everyone was in love with consumer unicorns again. Now investors are licking their wounds, except for those who eschewed the name brands and went for boring old B2B and infrastructure companies. They are doing just fine, thank you.

Why are investors overpaying for household-name unicorns? Is it that they really believe they are good assets, or are other factors at play? The fact is that venture funds and private equity funds are competing for investment funds themselves. I am personally an investor in several venture funds, and I have heard the pitch, “we were investors in Facebook, Instagram, Uber, Twitter (or whatever), and we can get you access to these deals.” Sounds good, but what they don’t tell you is how much they paid (or overpaid) to be part of these deals. It’s such nonsense and the perennially poor returns delivered by the ego-driven venture capital industry are its just rewards.

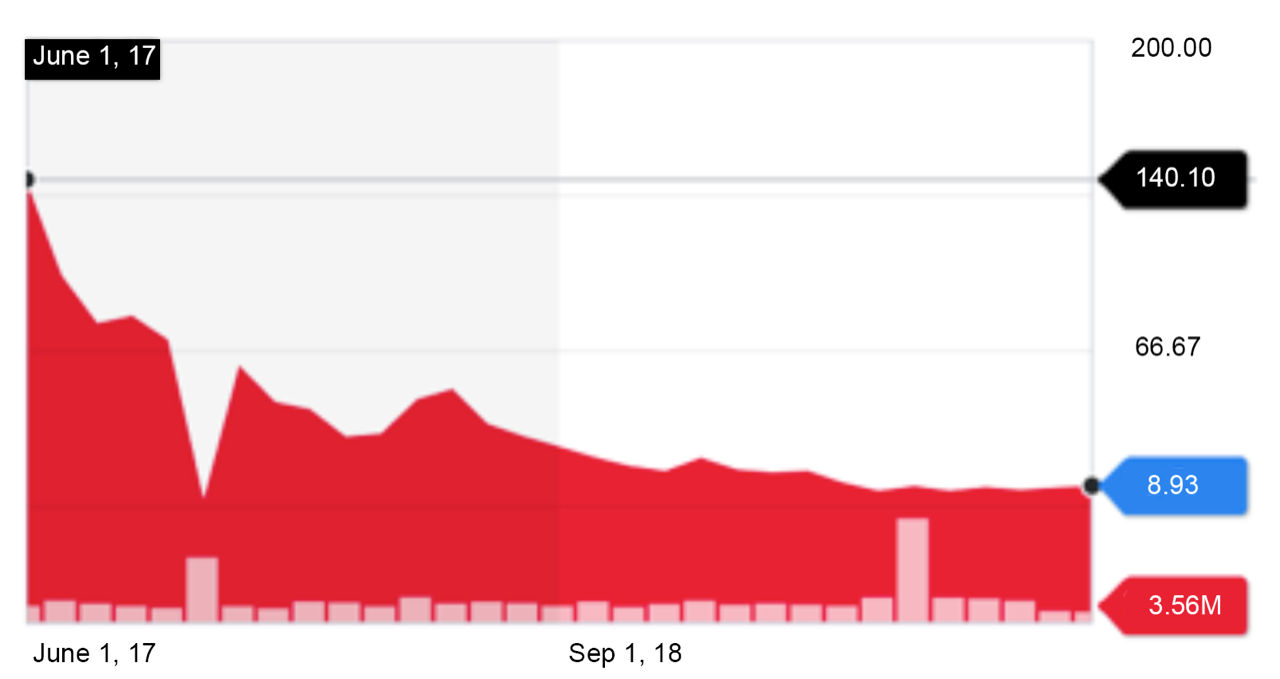

Downward stock valuations of unicorns post-IPO. (Yahoo Finance)

Investors who bid up the valuations of high-profile unicorns are of course hoping that an IPO will eventually bail them out. The problem is that public fund managers, like Fidelity or Blackstone, who control most of post-IPO stocks, look at the value of a company quite differently. They see a company’s “value” as the sum total of all the company’s future profits. They can’t offer their clients “exclusive” access to hot deals. We’re talking public stocks that anyone can buy.

If nobody can see a clear road to profitability, then this hard-nosed approach to valuation will lead to stocks tanking after an IPO. That’s recently been the case with We, Uber, and numerous others.

From 2010 to the first quarter of 2015, investors collectively poured $9.4 billion into the on-demand economy, according to data from CB Insights. Uber accounted for 58% of the $4.12 billion raised in 2014. What’s also striking is how quickly the industry piled onto the latest thing between 2013 and 2014. Since its IPO in May of 2019, Uber’s stock has fallen nearly 40% from its peak, Lyft is down even more, and Softbank’s most recent investment in We appears to have wiped out nearly 80% of its previous private valuation. Masayoshi Son has been publicly apologizing for his investment in We: “My investment judgment was poor in many ways,” said Son.

In 2015, Blue Apron had raised $190 million in funding with a valuation of $2 billion in revenues of just $40M. Since their IPO in June 2017, their stock price has fallen by 94%, with their market cap today at a mere $101 million.

Illustration: Wasabi

The plaques commemorating investments in companies like We, Blue Apron, and the like have turned from being great marketing assets to being symbols of over-zealous, undisciplined investing. Whereas four or five years ago, everyone was talking about how the service economy was reshaping the world, now the headlines have turned to how the market has burned out on over-hyped unicorns. Here are some typical current headlines, from Quartz, “Peloton staggers to IPO as investors sour on unprofitable unicorns,” or from The New York Times, “WeWork’s Efforts to Salvage I.P.O. Renew Fears About ‘Unicorn’ Era,” or from the New York Post, “WeWork is proof that the IPO market is in trouble.”

The desire to have high-profile consumer names in the portfolio creates distortions in the market. Instead of companies getting valued on the basis of their earnings potential, their values get distorted by the desire of investors to simply have these names in their portfolios at any cost lest they be tarred for missing the boat.

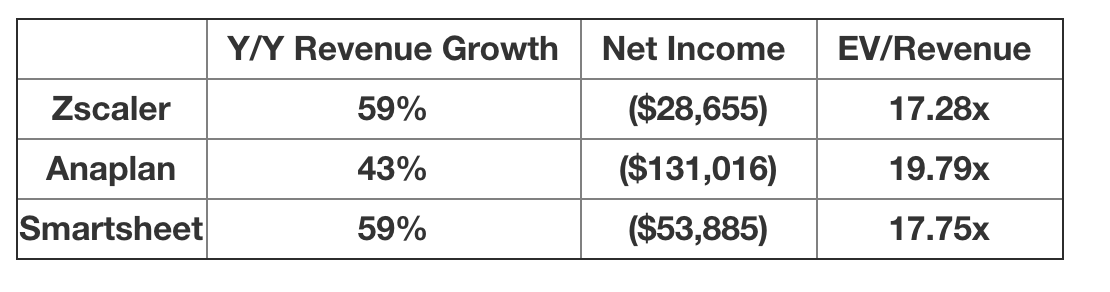

So much for the sexy “change the world” names. There are unicorns out there whose names hardly anyone recognizes, such as Zscaler, Anaplan, and Smartsheet because they mostly sell business-to-business software or cloud services. But all of them are trading significantly above their IPO price.

What these three companies have in common is that they are 1) all losing money, 2) all growing rapidly, and 3) all trading at very high multiples of revenue.

Profitability is tied to growth. You can have one or the other, but rarely both simultaneously. With subscription businesses like SaaS, the payback on customer acquisition is not fully realized for several years, hence current year’s profitability does not truly reflect the value of the business. What differentiates these little-known unicorns from their consumer brethren is that their basic business model is profitable. You can pull back on selling, general and administrative expenses (SG&A) at any time, and the money will just keep pouring in.

Profitability is tied to growth. You can have one or the other, but rarely both simultaneously. With subscription businesses like SaaS, the payback on customer acquisition is not fully realized for several years, hence current year’s profitability does not truly reflect the value of the business. What differentiates these little-known unicorns from their consumer brethren is that their basic business model is profitable. You can pull back on selling, general and administrative expenses (SG&A) at any time, and the money will just keep pouring in.

For example, in the case of Zscaler, they lost $28.7 million in the most recent year, but SG&A was $217 million. All you’d have to do is cut back on sales and marketing and this company would turn solidly profitable at any time. With a subscription-based business model with low churn, every dollar of new revenue probably is worth $6-7 of long-term value. So, what these companies have (as does my last company, Carbonite) is a machine where you can put a dollar in the hopper, turn the marketing crank, and 6 or 7 dollars of long-term value comes out the bottom.

What gets lost with companies like We is that the underlying business model may never be profitable. There is so little stickiness in the customer base that the long-term value of a sale is not much higher than the current revenue, hence there’s no way to pull in your horns on SG&A and suddenly make money.

So when you read headlines about how investors are growing weary of money-losing unicorns, there are two things to consider, first, does current revenue really reflect the long-term value of the customer base, and second, to what extent does the ownership of a high-profile name distort its value.

Someone recently asked me for advice on hiring, and one of my answers was “Beware of charisma.” The same thing applies to stocks. There are sexy companies and there are boring companies. I prefer the latter.

A good business model is a good business model no matter where you are in the fashion cycle.