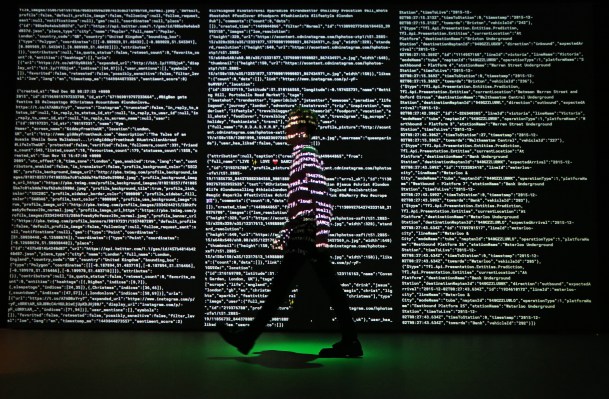

A posthumous manifesto by Giovanni Buttarelli, who until his death this summer was Europe’s chief data protection regulator, seeks to join the dots of surveillance capitalism’s rapacious colonization of human spaces, via increasingly pervasive and intrusive mapping and modelling of our data, with the existential threat posed to life on earth by manmade climate change.

In a dense document rich with insights and ideas around the notion that “data means power” — and therefore that the unequally distributed data-capture capabilities currently enjoyed by a handful of tech platforms sums to power asymmetries and drastic social inequalities — Buttarelli argues there is potential for AI and machine learning to “help monitor degradation and pollution, reduce waste and develop new low-carbon materials”. But only with the right regulatory steerage in place.

“Big data, AI and the internet of things should focus on enabling sustainable development, not on an endless quest to decode and recode the human mind,” he warns. “These technologies should — in a way that can be verified — pursue goals that have a democratic mandate. European champions can be supported to help the EU achieve digital strategic autonomy.”

“The EU’s core values are solidarity, democracy and freedom,” he goes on. “Its conception of data protection has always been the promotion of responsible technological development for the common good. With the growing realisation of the environmental and climatic emergency facing humanity, it is time to focus data processing on pressing social needs. Europe must be at the forefront of this endeavour, just as it has been with regard to individual rights.”

One of his key calls is for regulators to enforce transparency of dominant tech companies — so that “production processes and data flows are traceable and visible for independent scrutiny”.

“Use enforcement powers to prohibit harmful practices, including profiling and behavioural targeting of children and young people and for political purposes,” he also suggests.

Another point in the manifesto urges a moratorium on “dangerous technologies”, citing facial recognition and killer drones as examples, and calling generally for a pivot away from technologies designed for “human manipulation” and toward “European digital champions for sustainable development and the promotion of human rights”.

In an afterword penned by Shoshana Zuboff, the US author and scholar writes in support of the manifesto’s central tenet, warning pithily that: “Global warming is to the planet what surveillance capitalism is to society.”

There’s plenty of overlap between Buttarelli’s ideas and Zuboff’s — who has literally written the book on surveillance capitalism. Data concentration by powerful technology platforms is also resulting in algorithmic control structures that give rise to “a digital underclass… comprising low-wage workers, the unemployed, children, the sick, migrants and refugees who are required to follow the instructions of the machines”, he warns.

“This new instrumentarian power deprives us not only of the right to consent, but also of the right to combat, building a world of no exit in which ignorance is our only alternative to resigned helplessness, rebellion or madness,” she agrees.

There are no less than six afterwords attached to the manifesto — a testament to the store in which Buttarelli’s ideas are held among privacy, digital and human rights campaigners.

The manifesto “goes far beyond data protection”, says writer Maria Farrell in another contribution. “It connects the dots to show how data maximisation exploits power asymmetries to drive global inequality. It spells out how relentless data-processing actually drives climate change. Giovanni’s manifesto calls for us to connect the dots in how we respond, to start from the understanding that sociopathic data-extraction and mindless computation are the acts of a machine that needs to be radically reprogrammed.”

At the core of the document is a 10-point plan for what’s described as “sustainable privacy”, which includes the call for a dovetailing of the EU’s digital priorities with a Green New Deal — to “support a programme for green digital transformation, with explicit common objectives of reducing inequality and safeguarding human rights for all, especially displaced persons in an era of climate emergency”.

Buttarelli also suggests creating a forum for civil liberties advocates, environmental scientists and machine learning experts who can advise on EU funding for R&D to put the focus on technology that “empowers individuals and safeguards the environment”.

Another call is to build a “European digital commons” to support “open-source tools and interoperability between platforms, a right to one’s own identity or identities, unlimited use of digital infrastructure in the EU, encrypted communications, and prohibition of behaviour tracking and censorship by dominant platforms”.

“Digital technology and privacy regulation must become part of a coherent solution for both combating and adapting to climate change,” he suggests in a section dedicated to a digital Green New Deal — even while warning that current applications of powerful AI technologies appear to be contributing to the problem.

“AI’s carbon footprint is growing,” he points out, underlining the environmental wastage of surveillance capitalism. “Industry is investing based on the (flawed) assumption that AI models must be based on mass computation.

“Carbon released into the atmosphere by the accelerating increase in data processing and fossil fuel burning makes climatic events more likely. This will lead to further displacement of peoples and intensification of calls for ‘technological solutions’ of surveillance and border controls, through biometrics and AI systems, thus generating yet more data. Instead, we need to ‘greenjacket’ digital technologies and integrate them into the circular economy.”

Another key call — and one Buttarelli had been making presciently in recent years — is for more joint working between EU regulators towards common sustainable goals.

“All regulators will need to converge in their policy goals — for instance, collusion in safeguarding the environment should be viewed more as an ethical necessity than as a technical breach of cartel rules. In a crisis, we need to double down on our values, not compromise on them,” he argues, going on to voice support for antitrust and privacy regulators to co-operate to effectively tackle data-based power asymmetries.

“Antitrust, democracies’ tool for restraining excessive market power, therefore is becoming again critical. Competition and data protection authorities are realising the need to share information about their investigations and even cooperate in anticipating harmful behaviour and addressing ‘imbalances of power rather than efficiency and consent’.”

On the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) specifically — Europe’s current framework for data protection — Buttarelli gives a measured assessment, saying “first impressions indicate big investments in legal compliance but little visible change to data practices”.

He says Europe’s data protection authorities will need to use all the tools at their disposal — and find the necessary courage — to take on the dominant tracking and targeting digital business models fuelling so much exploitation and inequality.

He also warns that GDPR alone “will not change the structure of concentrated markets or in itself provide market incentives that will disrupt or overhaul the standard business model”.

“True privacy by design will not happen spontaneously without incentives in the market,” he adds. “The EU still has the chance to entrench the right to confidentiality of communications in the ePrivacy Regulation under negotiation, but more action will be necessary to prevent further concentration of control of the infrastructure of manipulation.”

Looking ahead, the manifesto paints a bleak picture of where market forces could be headed without regulatory intervention focused on defending human rights. “The next frontier is biometric data, DNA and brainwaves — our thoughts,” he suggests. “Data is routinely gathered in excess of what is needed to provide the service; standard tropes, like ‘improving our service’ and ‘enhancing your user experience’ serve as decoys for the extraction of monopoly rents.”

There is optimism too, though — that technology in service of society can be part of the solution to existential crises like climate change; and that data, lawfully collected, can support public good and individual self-realization.

“Interference with the right to privacy and personal data can be lawful if it serves ‘pressing social needs’,” he suggests. “These objectives should have a clear basis in law, not in the marketing literature of large companies. There is no more pressing social need than combating environmental degradation” — adding that: “The EU should promote existing and future trusted institutions, professional bodies and ethical codes to govern this exercise.”

In instances where platforms are found to have systematically gathered personal data unlawfully Buttarelli trails the interesting idea of an amnesty for those responsible “to hand over their optimisation assets”– as a means of not only resetting power asymmetries and rebalancing the competitive playing field but enabling societies to reclaim these stolen assets and reapply them for a common good.

While his hope for Europe’s Data Protection Board — the body which offers guidance and coordinates interactions between EU Member States’ data watchdogs — is to be “the driving force supporting the Global Privacy Assembly in developing a common vision and agenda for sustainable privacy”.

The manifesto also calls for European regulators to better reflect the diversity of people whose rights they’re being tasked with safeguarding.

The document, which is entitled Privacy 2030: A vision for Europe, has been published on the website of the International Association of Privacy Professionals ahead of its annual conference this week.

Buttarelli had intended — but was finally unable — to publish his thoughts on the future of privacy this year, hoping to inspire discussion in Europe and beyond. In the event, the manifesto has been compiled posthumously by Christian D’Cunha, head of his private office, who writes that he has drawn on discussions with the data protection supervisor in his final months — with the aim of plotting “a plausible trajectory of his most passionate convictions”.